How Mobile Today Is Like TV Six Decades Ago

All of the growth in advertising right now is targeted at that little screen people carry with them everywhere.

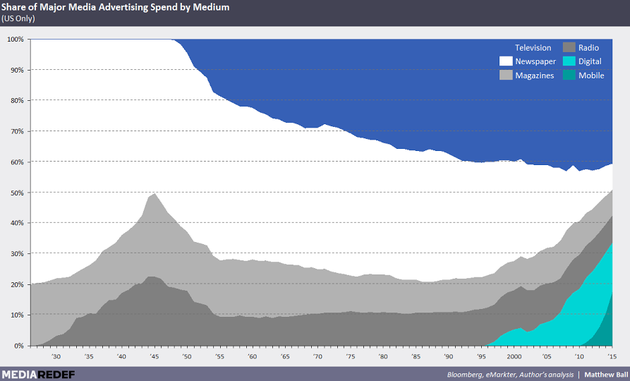

In the early 1950s, television was popular, but unsophisticated. This was a common sentiment, even among the people who produced it—"a hybrid monstrosity derived from newspapers, radio news, and newsreels, which inherited none of the merits of its ancestors," as one CBS News anchor summed it up. But either despite its gimmicky shortcomings or because of them, advertisers loved the little box. Revenue from ads increased more than 60 percent a year for the first five years of the decade, so that by 1955, television accounted for nearly 20 percent of total U.S. media advertising.

This year, mobile media accounts for the exact same share, nearly 20 percent of total U.S. media spending. So, in a very real way, mobile is today where television was exactly six decades ago.

For more than a century, media organizations working in newspapers, magazines, television, and radio have relied on advertising to report and publish the news. It was a sometimes awkward, and often fruitful, symbiosis of needs. The news created an audience of readers, the advertiser paid to piggyback off that audience, and this commercial tag-team subsidized both reportage and readership.

That’s precisely why anybody in the news business should be more than a little alarmed at the recent migration patterns in advertising, exhaustively documented in the Pew Research Center’s State of the News Media report. In a sentence, digital is eating legacy media, mobile is eating digital, and two companies, Facebook and Google, are eating mobile. Here is the broader scary story in four charts, from the Pew report and from other sources supporting up its main points.

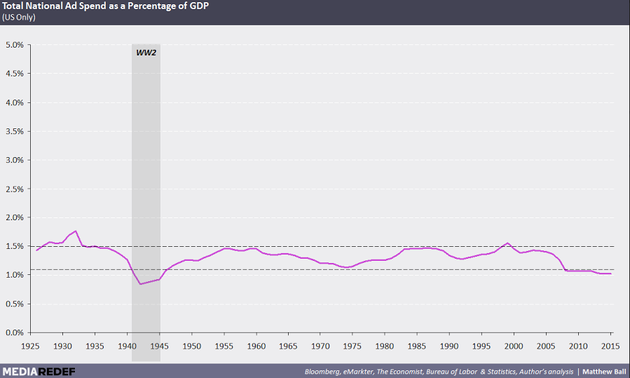

1. U.S. advertising is declining as a share of GDP. Total national ad spending, as a percentage of the economy, has fallen by a third since 2000 and now hovers near its lowest levels since the end of World War II, before the rise of television.

It wouldn’t be such a bad thing that advertising is declining as a share of the economy if news publishers held a steady or growing percent of the market. But the opposite is happening...

2. The entire net growth is U.S. advertising is digital. Between 2011 non-digital advertising fell from $126 billion to $123 billion. During the same period, digital advertising doubled from $32 billion to $60 billion. Newspapers are getting pinched. Newspaper advertising revenue and newspaper employment have both fallen to 60-year lows, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Newspaper Association of America.

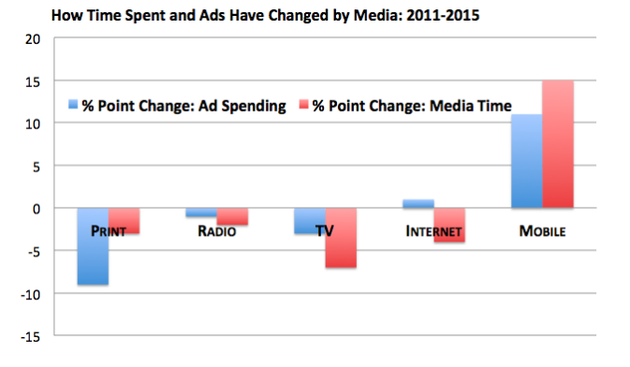

3. The entire net growth in digital advertising is happening in mobile. Since 2011, desktop advertising has fallen by about 10 percent, according to Pew. Meanwhile mobile advertising has grown by a factor of 30, reaching about $32 billion in 2015. This dovetails with analysis from the digital-media analyst Mary Meeker, whose recent report on media time and advertising found that in the last five years, mobile grew at the expense of every other media platform. (The chart below was made with data from her report.)

4. Two companies, Facebook and Google, control half of net mobile ad revenue. As I’ve written before, digital media today is led by a historically extraordinary duumvirate. In television, four large media companies account for half of all cable advertising, according to an analysis by the digital-media analyst Matthew Ball. They are Time Warner, Disney, NBCUniversal, and 21st Century Fox. But just two companies, Facebook and Google, account for half of all digital-media advertising. As my colleague Adrienne LaFrance writes today, as far as most digital publishers are concerned, Facebook is the universe.

At the same time that access to news media is getting democratized—the internet is theoretically an all-access platform for broadcasting ideas—the business of media advertising seems to be concentrating. In the 1940s, newspapers’ and magazines’ ad revenue was divided across thousands of publishers. In the 1990s and 2000s, television ad revenue was dominated by five or six entertainment companies, like Time Warner and Disney. Now two tech companies own half the digital market for ads. The New York Times was never “newspapers.” NBC was never “television.” But Facebook and Google are “the internet.”

What does this mean for the future of news? To acknowledge this shift toward mobile is not to embrace a doom-and-gloom mindset. It is happening, full stop, and people can choose for themselves to be optimists or pessimists about the economic future of the news.

For newspapers, magazines, and websites, there are several paths forward. First, billionaires can rescue media organizations from the stormy seas of the mobile Internet and fund journalism that the ad market won’t support. Second, companies like Facebook may determine that it is in their own interest to preserve some news and entertainment publishers, and they will directly pay media companies, the same way cable companies pay carriage to television channels. Third, more media companies could ask readers to pay directly for the news and shift their business back to subscriptions. Fourth, companies forced to find sources of revenue beyond digital advertising could find new ways to move their brands into higher-margin (hopefully) businesses, like events (e.g. the New Yorker Festival) and marketing (e.g. BuzzFeed’s digital-media ad team). Fifth, some news publishers, particularly those with massive scale, could eventually figure out a sturdy advertising model based on sponsored posts, banners, and video to support their work independently.

Some historical perspective could be illuminating. Because despite its rapid intrusion into the market for advertising, television did not destroy newspapers, magazines, or radio. A more diverse media ecosystem learned to coexist.

In mobile history, the year is 1955. Facebook and Google are dominant for now. But if there's one lesson from the history of American entertainment and media, it's this: Things change. News survives.