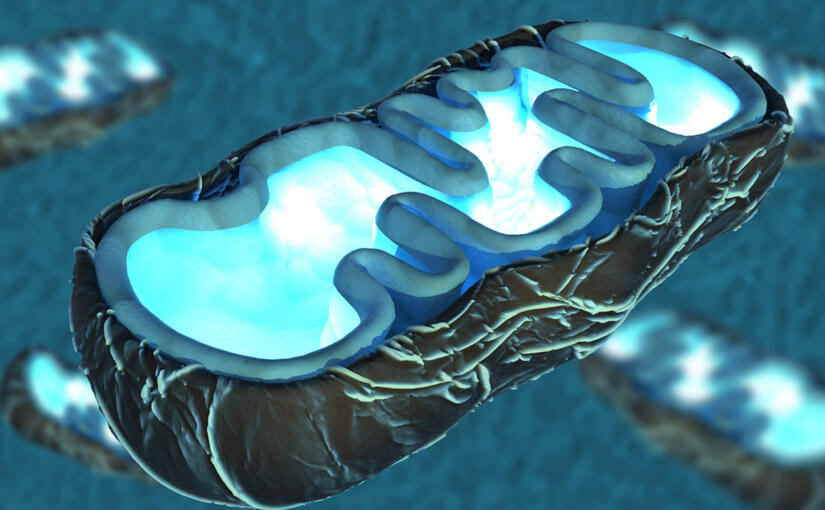

Mitochondrial disease (mito) is a genetic condition which can be caused by a mutation in the mitochondrial DNA passed from a mother to her child.

Mito is difficult to diagnose as symptoms can range from mild to severe and can impact many different organs and body systems. The most severe forms of mito can lead to mortality or significant disability.

Currently the treatment options for mito are limited so preventative options are very important to avoid the devastating impacts on individuals and families.

Some options are available at the moment for women who are planning a family and are at increased risk of having a child with mito. Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) using donated eggs are possibilities but PGD is not suitable for women at high risk of having a child with mito. Another option may be on the horizon for couples to have children who are genetically related to both parents; mitochondrial donation.

The technique involves replacing the mitochondrial DNA in the mother’s egg with DNA from a donor egg. This represents less than 0.1% of the mother’s genetic material that is being passed on to her baby, but when a mother has a high risk of passing on mutated mitochondrial DNA, this could save her child from a potentially life-threatening or highly debilitating illness.

Currently the practice is illegal in Australia as it contravenes laws against cloning and research involving human embryos. However, in June 2018 the Senate Community Affairs References Committee recommended that the government begin taking steps towards potentially legalising mitochondrial donation.

Professor David Thorburn is co-Group Leader of Brain & Mitochondrial Research at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and has worked on mito for over 25 years. He is also a founding director of the Mito Foundation and the Chair of their Scientific & Medical Advisory Panel. We asked Prof Thorburn some questions about mitochondrial donation.

- How does a woman know she is a carrier of mito?

Most women don’t know they have a chance to pass on mito. Some families have strong maternal histories with multiple cases of mito being passed down maternal lines so the risk is clear. Some women may also have found out about their mito risk after having a child die in infancy. Sometimes a woman may have a child with severe mito and then had genetic testing herself for mutations. On closer questioning and investigation doctors may uncover symptoms in the mother that were not previously attributed to mito such as problems with sight, mild hearing loss or exercise intolerance. More often than not there is no known family history.

- Can women be screened before conception?

It is possible for women at high risk, who have a family history of mito to be screened. As with most other genetic diseases we do not have broad population screening.

This is in part because it is much harder to screen for mitochondrial DNA as some mutations can disappear from the blood with age so would not show up on a blood test. We can use a muscle biopsy to test for mito but this is more invasive so we often test urine as the mutation can be present in urine sediment when not detectable in the blood. However, in around a quarter of cases where the child is diagnosed with mito, no mutation is detected in the mother when she is tested. This may be due to what’s known as a de novo event – a one off mutation in that single egg that was fertilised that led to the child having mito. Due to these complexities it is currently impractical to screen all women for mito.

- How many births could be helped by the introduction of mitochondrial donation?

Based on studies from the UK and extrapolated to the Australian context, the Mito Foundation estimates about 56 births per year in Australia are at high risk of having a child with mito.

Only a proportion of those would be wanting to access mito donation as current options are suitable for some couples, including prenatal diagnosis, preimplantation genetic diagnosis or using a full donor egg for IVF. These may be the preferred options for a woman depending on her circumstances and in many cases a woman may need to try one of these options first before being able to access mitochondrial donation.

- How will babies be monitored for complications?

There has been extensive research done in the UK to ensure this technique is as safe as possible. The first families to use the technique in Australia would be part of a clinical trial. In the UK model families gave consent for samples such as umbilical cord and the newborn blood screening spots to be kept for pathology testing. This looked for the mutation that the mother had to see if it had been passed to the child – and how much of that mutated DNA the child had received. During their development a child would have some extra tests but these would be done with the normal checks that children receive in their early life, checking again for the presence of the mutation and any change in the amount of that DNA.

Australia is well regarded as a leading nation in mitochondrial diagnosis and IVF technologies. This technique requires significant expertise in molecular testing and reproductive biology. The Senate committee examined the provision of pathology services and were reassured that the accreditation and quality systems that Australian pathology laboratories adhere to are first class. This would enable the ground-breaking technique of mitochondrial donation to become a reality for Australian families.