The FT today published a fascinating interview with Thomas Middelhoff, the former CEO of Bertelsmann, the German media giant. Middelhoff became a star during the dot-com boom—his $50 million investment in AOL became a $7 billion exit five years later—and then his star fell. Middelhoff ended up sentenced to three years in prison after being found guilty of 27 counts of embezzlement and three counts of tax evasion in 2014.

Middelhoff’s crimes were not the kind of thing that would land an American executive in jail: Mostly, they centered on his predilection for taking a helicopter to work to avoid nasty traffic jams. He billed those expenses to the company, but they had never been authorized, and he should have paid for them himself.

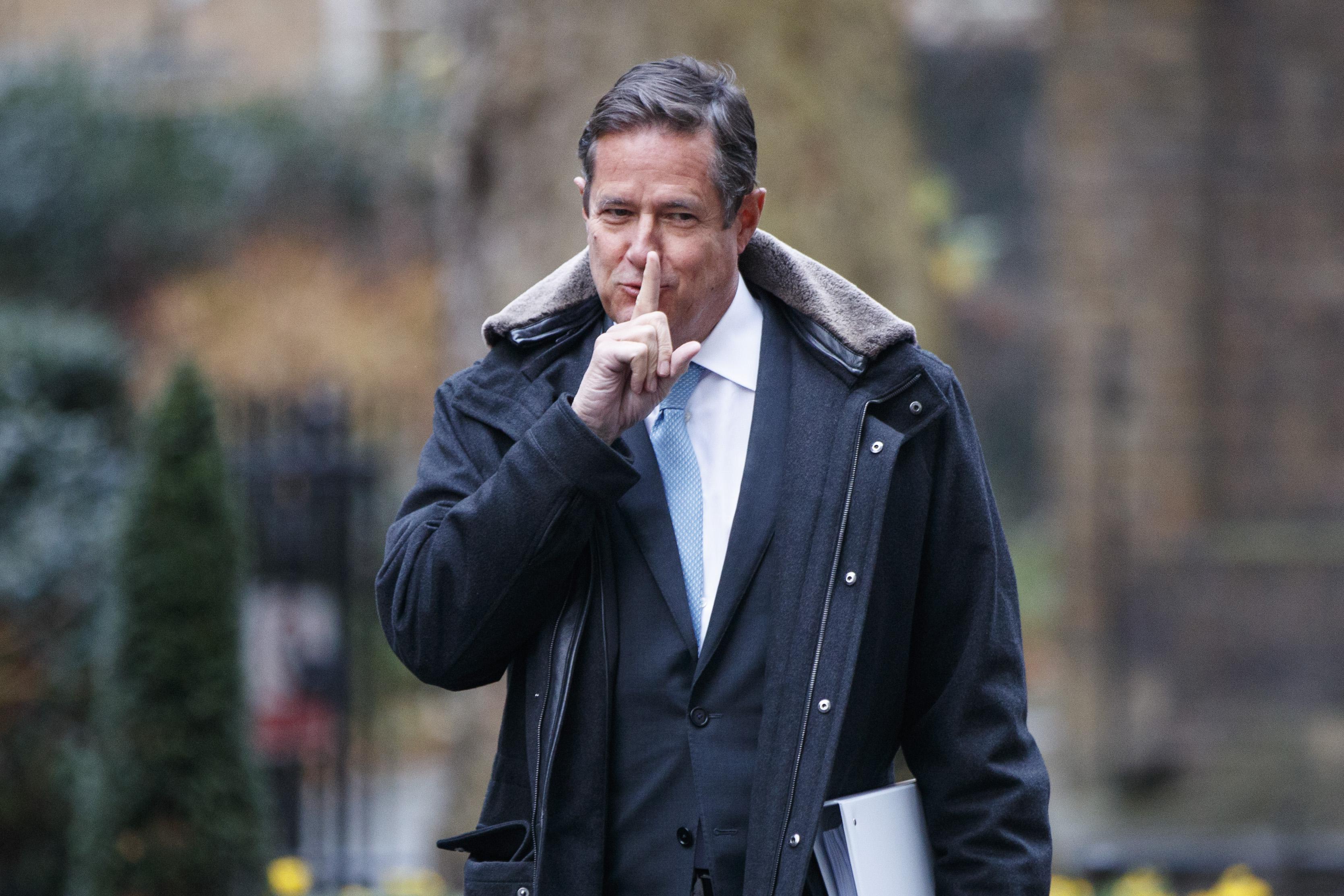

Meanwhile, in London, Barclays CEO Jes Staley has been fined $870,000 for attempting to identify a whistleblower who complained about the way that the bank hired one of Staley’s friends; the bank’s board has also clawed back some $680,000 from Staley’s annual bonus.

Middelhoff, now out of jail and claiming to have lost all of his wealth, is at peace with his prison sentence, and has come to hate his former self, the arrogant and narcissistic CEO who craved affirmation and who failed to hold himself to the same standards he demanded of everybody else. He told the FT that he’s rediscovered his Catholic faith, and talked about learning humility.

Staley hasn’t quite had the same kind of come-to-Jesus moment, but did put out an apologetic statement saying that his behavior was inappropriate.

Can we take either of these two stories of punishment and contrition entirely at face value? Almost certainly not. I find it very hard to believe that Middelhoff is as broke as he says he is. But the fact remains that in both cases a high-profile CEO has been handed down a very public punishment by his government, and in both cases he has accepted that punishment as being entirely legitimate.

Now try to think of a similar case in the U.S.

It’s not easy. Even Enron’s Ken Lay, who managed to destroy more than $60 billion in value at a company built on fraud, had his conviction posthumously vacated; the former CEO, Jeff Skilling, is alive and unapologetic. Indeed, the trend in American corporate governance, at least when it comes to chief executives, seems to be towards less accountability, not more. The rise of the unicorns has meant that hundreds of CEOs of billion-dollar corporations do not need to answer to the SEC; many of them have also retained voting control of their companies, which means they’re not even answerable to their boards. When Snap went public, the shares it sold were all non-voting; the company is entirely controlled by its two co-founders. And with laissez-faire Trump appointees running the entire executive branch, including the SEC and the DOJ, it’s hard to imagine much in the way of criminal indictments against CEOs any time soon.

In recent weeks, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has made semi-friendly noises about being open to regulation, as long as it’s the kind of regulation he approves of. But there’s a huge difference between regulation, on the one hand, and actual accountability, on the other. Increasingly, America is becoming a country owned and run by men like the Koch brothers, who run their multi-billion-dollar business empire while receiving politicians as supplicants, and who are de facto answerable to no one. It’s deeply unhealthy, on a societal level, but we’ve also normalized it. It’s only by looking to Europe that we can see how a capitalist system can—and should—be run.