Introduction

When looking at a visual, we can usually immediately say whether it is appealing or amiss. (Because they often play out at the visceral level in Don Norman’s model of emotional design.) However, few can verbalize why a layout is visually attractive. Graphics that take advantage of the principles of good visual design can drive engagement and increase usability.

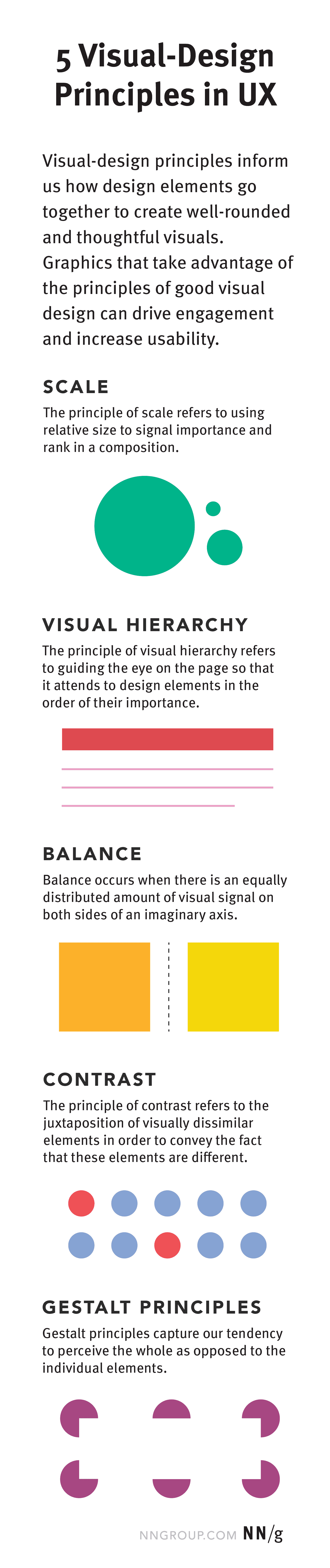

Visual-design principles inform us how design elements such as line, shape, color, grid, or space go together to create well-rounded and thoughtful visuals.

This article defines 5 visual-design principles that impact UX:

- Scale

- Visual hierarchy

- Balance

- Contrast

- Gestalt

Following these 5 visual-design principles can drive engagement and increase usability.

1. Scale

This principle is commonly used: almost every good visual design takes advantage of it.

The principle of scale: Using relative size to signal importance and rank in a composition.

In other words, when this principle is used properly, the most important elements in a design are bigger than the ones that are less important. The reason behind this principle is simple: when something is big, it’s more likely to be noticed.

A visually pleasing design generally uses no more than 3 different sizes. Having a range of differently sized elements will not only create variety within your layout, but it will also establish a visual hierarchy (see next principle) on the page. Be sure to emphasize the most important aspect of your design by making them biggest.

When the principle of scale is used properly and the right elements are emphasized, users will easily parse the visual and know how to use it.

2. Visual Hierarchy

A layout with a good visual hierarchy will be easily understood by your users.

The principle of visual hierarchy: Guiding the eye on the page so that it attends to different design elements in the order of their importance.

Visual hierarchy can be implemented through variations in scale, value, color, spacing, placement, and a variety of other signals.

Visual hierarchy controls the delivery of the experience. If you have a hard time figuring out where to look on a page, it’s more than likely that its layout is missing a clear visual hierarchy.

To create a clear visual hierarchy, use 2–3 typeface sizes to indicate to users what pieces of content are most important or at the highest level in the page’s mini information architecture. Or, consider using bright colors for important items and muted colors for less important ones.

Scale can also help define the visual hierarchy, so incorporate various scales for your different design elements. A general rule of thumb is to include small, medium, and large components in the design.

3. Balance

Balance is like a seesaw: instead of weight, you are balancing design elements.

The principle of balance: A satisfying arrangement or proportion of design elements. Balance occurs when there is an equally distributed (but not necessarily symmetrical) amount of visual signal on both sides of an imaginary axis going through the middle of the screen. This axis is often vertical but can also be horizontal.

Just like when balancing weight, if you were to have one small design element and one large design element on the two sides of the axis, the design would feel a bit unbalanced. The area taken by the design element matters when creating balance, not just the number of elements.

The imaginary axis you establish on your visual will be the reference point for how to organize your layout and will help you understand the current state of balance on your visual. In a balanced design, no one area draws your eye so much that you can’t see the other areas (even though some elements might carry more visual weight and be focal points). Balance can be:

- Symmetrical: elements are symmetrically distributed relative to the central imaginary axis

- Asymmetrical: elements are asymmetrically distributed relative to the central axis

- Radial: elements radiate out from a central, common point in a circular direction.

The kind of balance you use in your visual depends on what you want to convey. Asymmetry is dynamic and engaging. It creates a sense of energy and movement. Symmetry is quiet and static. Radial balance will always lead the eye to the center of the composition.

4. Contrast

This is another commonly used principle that makes certain parts of your design stand out to your users.

The principle of contrast: The juxtaposition of visually dissimilar elements in order to convey the fact that these elements are different (e.g., belong in different categories, have different functions, behave differently).

In other words, contrast provides the eye with a noticeable difference (e.g., in size or color) between two objects (or between two sets of objects) in order to emphasize that they are distinct.

The principle of contrast is often applied through color. For example, red is frequently used in UI designs, especially on iOS, to signify deleting. The bright color signals that a red element is different from the rest.

Often, in UX the word “contrast” brings to mind the contrast between text and its background. Sometimes designers deliberately decrease the text contrast in order to deemphasize less important text. But this approach is dangerous — reducing text contrast also reduces legibility and may make your content inaccessible. Use a color-contrast checker to ensure that your content can still be read by all your target users.

5. Gestalt Principles

These are a set of principles that were established in the early twentieth century by the Gestalt psychologists. They capture how humans make sense of images.

Gestalt principles: Principles that explain how humans simplify and organize complex images that consist of many elements, by subconsciously arranging the parts into an organized system that creates a whole, rather than interpreting them as a series of disparate elements. In other words, Gestalt principles capture our tendency to perceive the whole as opposed to the individual elements.

There are several Gestalt principles, including similarity, continuation, closure, proximity, common region, figure/ground, and symmetry and order. Proximity is especially important for UX — it refers to the fact that items that are visually closer together are perceived as part of the same group.

Why Visual-Design Principles are Important

Why should we care about and understand visual-design principles? Beyond making something “look pretty,” understanding and taking advantage of them serves to:

- Increase usability. Following these visual-design principles often results in layouts that are easy to use. For example, the golden ratio, which is frequently used for creating beautiful works of art was also used in typesetting to create a visually pleasing relationship between font size, line height, and line width. The result typically led to shortened line lengths, which created balance (via white space) on a webpage and made the text easier to read. When paired with a strong interaction design, visual design will increase task success rates and user engagement.

- Provoke emotion and delight. Beautiful things elicit positive emotions. (In fact, the aesthetic–usability effect says that when people find a design visually appealing, they may be more forgiving of minor usability mishaps.) By following the principles of good visual designs, designers can create UIs that look good and thus make users feel good.

- Strengthen brand perception. A strong visual system builds user trust and interest in the product and appropriately represents and reinforces the brand.

References

Lupton, E. (2008). Graphic Design: The New Basics. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Poulin, R. (2018). The Language of Graphic Design. Beverly: Quarto Publishing Group USA, Inc.