Showering Has a Dark, Violent History

In the 19th century, cold rinses and days-long baths became a way to treat—and control—psychiatric patients.

The 19th century was a time of great innovation in plumbing. Cities got the first modern sewers, with tunnels that snaked for miles underground. Houses got bathrooms, with ceramic toilets, tubs, and sinks that you would easily recognize today. And, not to be left behind in this period of infrastructure overhaul, psychiatric hospitals got hydrotherapy: the method of using water to treat madness.

By then, this curious idea was not new. In the 17th century, for example, the Flemish physician Jan Baptist van Helmont would plunge patients into ponds or the sea. His inspiration came from a story he’d heard of an escaping “lunatic” who ran right into a lake. The man nearly drowned, but when he recovered, so did his mind, apparently. Van Helmont concluded that water could stop “the too violent and exorbitant Operation of the fiery Life.” His began stripping his patients naked, binding their hands, and lowering them headfirst into the water, according to van Helmont’s son, who wrote a book about his father.

Van Helmont’s method was not practical or, frankly, safe: Patients sometimes drowned. It never did become common. But as large psychiatric hospitals opened and modern plumbing brought water indoors, hydrotherapy did indeed become a widespread treatment. It was a way of targeting the body to treat the mind, and it took on a greater variety of forms.

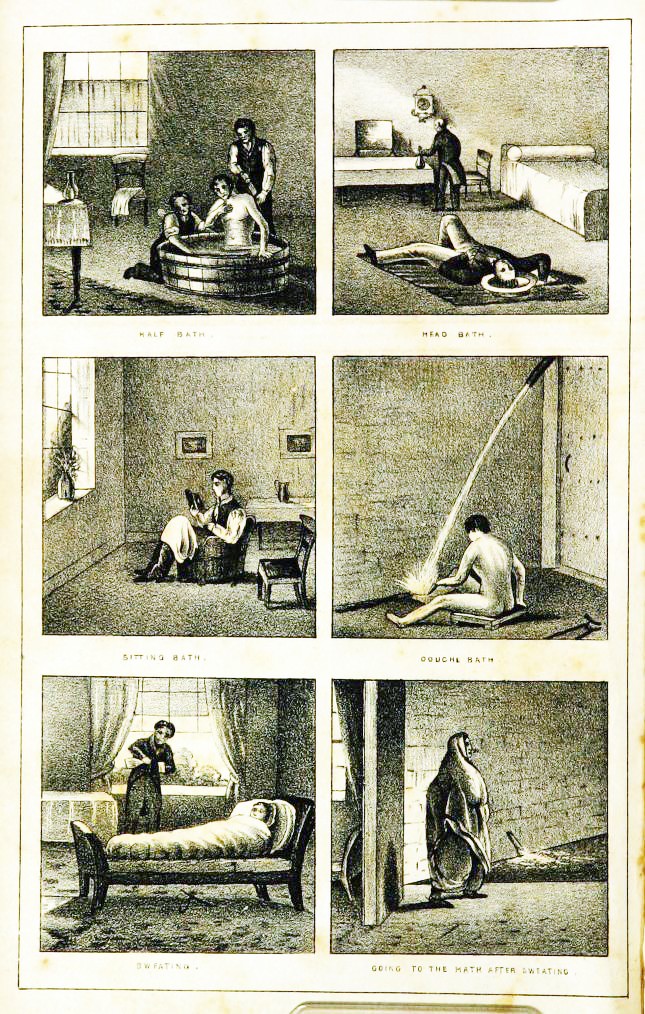

By the turn of the 19th century, doctors were homing in on the brain as the site of madness. So instead of plunging the entire body into water, some started directing cold showers onto patients’ heads to cool their “hot brains.” At its most simplistic, the technique requires nothing more than an attendant pouring water over the head of a restrained patient.

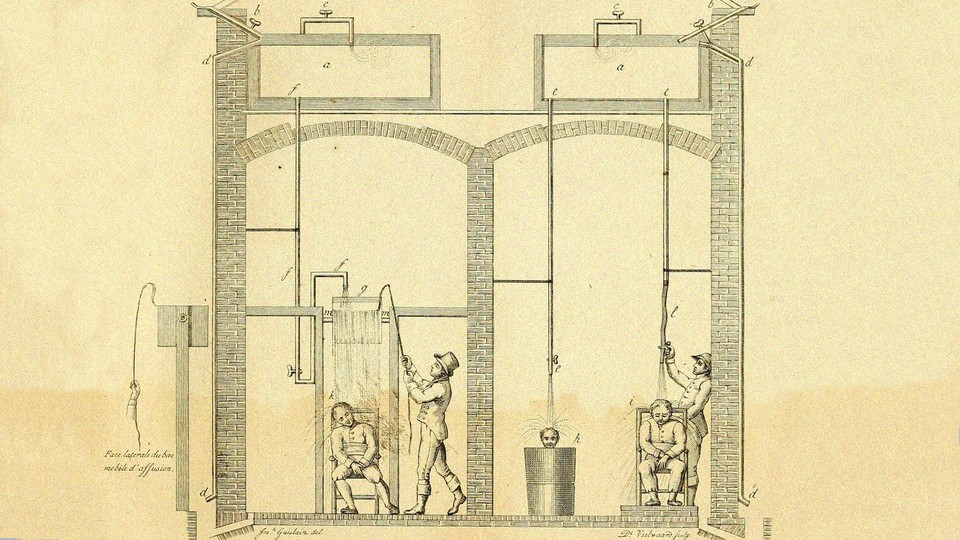

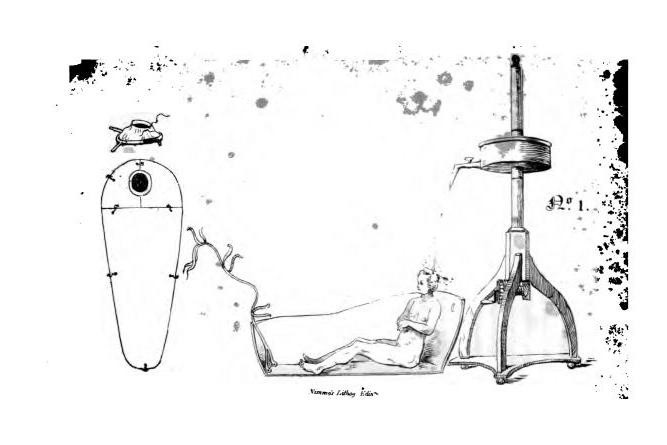

Physicians devised more elaborate mechanical showers, too. The Scottish physician Alexander Morison’s douche resembled a pod, in which a patient sat with his or her head poking out of a hole in the top. A stream of water poured down onto the patient from above. The Belgian physician Joseph Guislan designed a shower with its water reservoir set on an asylum’s roof. The patient sat bound to a chair, unable to see the attendant who would start the shower. “Shock and fear was part of the therapy,” says Stephanie Cox, a lecturer at Auckland University of Technology who authored a recent paper on the use of showers in asylums.

Later, hospitals also put patients in warm baths that lasted hours or even days. They wrapped patients tightly in wet sheets, then wrapped another rubber sheet around them, and let them sweat for hours. Physicians had various scientific-seeming explanations for such therapies: It relieved congestion in the brain. It eliminated toxins that cause insanity. “There were different post-hoc theories to try to make sense of it,” says Joel Braslow, a psychiatrist and history professor at UCLA. It is not, he adds, terribly different from how doctors try to explain antidepressants today. The drugs seem to work, but how exactly they work on the level of neurochemistry is still unclear, even as millions of people take them every day. “We see they have a certain effect on behavior and we see they have a biological effect and we try to argue backward,” Braslow says.

In his book, Mental Ills and Bodily Cures, Braslow writes that in hydrotherapy’s day, “a body of research based on precise measurements of parameters such as blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, and differential blood count lent support to this science.” Hospitals boasted of their expensive hydrotherapy facilities in annual reports.

At home, people were also experimenting with the new possibilities offered by modern plumbing. In her book All the Modern Conveniences, the historian Maureen Ogle writes of the “sheer whimsy” of showers that proliferated in homes in the early 19th century. “People were in a time not constrained by municipal ordinances,” she says, and bathroom fixtures had not yet become standardized. They had showers that aimed only at the torso and showers powered by foot pedals.

If the showers at home offered comfort, maybe even fun, the technology took on darker overtones in psychiatric hospitals. Many of the treatments involved physically restraining patients, whether in a shower or a tub or wrapped in wet sheets. At the same time, physicians believed that their treatments were genuinely scientifically motivated. “There is this hazy borderline between what counts as therapeutic and what counts as control and discipline,” Braslow says. This tension is present in any therapy that treats mental illness—even modern ones. “We define psychiatric illness by failure to function in the world,” he says, “so it is not surprising our interventions both act as social control and psychological control and also for comfort and consolation.”

Hydrotherapy eventually fell out of favor in the early 20th century with the advent of other treatments that require less-specialized infrastructure, such as electroshock therapy and, later, antipsychotic drugs. But it was one of the first treatments that focused on changing the physical body to treat the mind, suggesting a biological origin of mental illness—an idea taken almost for granted today.