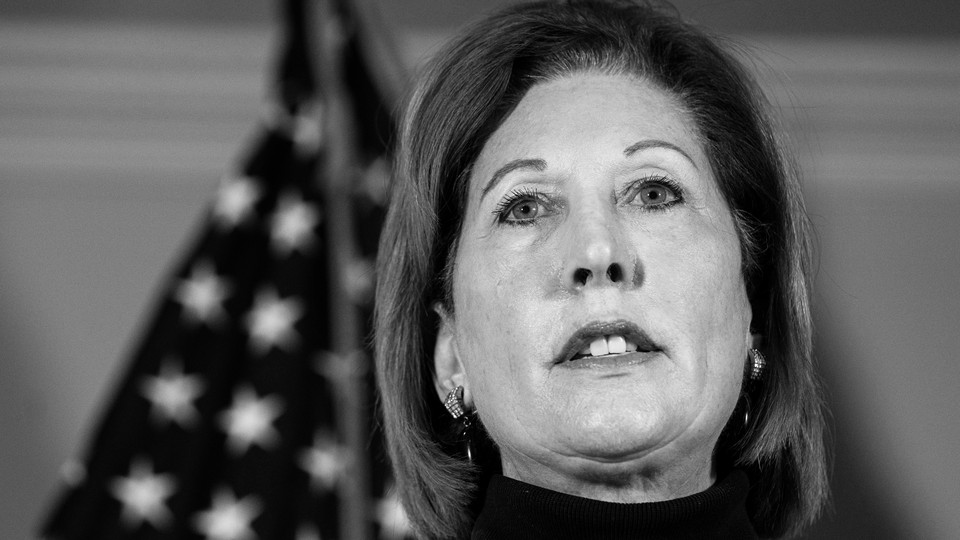

What Sidney Powell’s Deal Could Mean for the Fulton County Case Against Trump

“I think there are a lot of people who are in more trouble than they were before.”

The Kraken has been released—on probation.

Sidney Powell, the attorney who used that catchphrase for her work to overturn the 2020 presidential election, pleaded guilty today to six misdemeanors in Fulton County, Georgia, as part of a sweeping racketeering case against Donald Trump and 16 others. Under the terms of the deal, Powell admitted she conspired to breach the election systems in Coffee County, Georgia. She recorded a proffer video with prosecutors that described the crimes and she agreed to testify at future cases. She also wrote an apology letter to citizens of Georgia and agreed to pay almost $9,000 in fines.

The plea deal appears to be a very good one for Powell—letting her off with only misdemeanors, which can be wiped from her record as a first offender if she complies with the terms of the agreement. She was set to go on trial tomorrow, alongside the lawyer Kenneth Chesebro, who is accused of designing a scheme to submit false electors on behalf of Trump. (Powell still faces defamation charges from manufacturers of voting machines, and she’s an unindicted co-conspirator in Special Counsel Jack Smith’s federal case against Trump.)

“It’s a great deal. If I were her, I’d be very pleased,” Anthony Michael Kreis, a law professor at Georgia State, told me. “It’s a great outcome especially if you’re engaged in what most people would say are obvious felonies.”

The question is what it gives prosecutors. Although today’s plea doesn’t offer the public any new information about the prosecutors’ case or the evidence they have, it seems to have a potential to affect the overall Fulton County case in three ways. In short, Kreis told me, “I think there are a lot of people who are in more trouble than they were before.”

First, the plea simplifies the Chesebro trial. Powell and Chesebro had asked for speedy trials, rather than waiting a few months for a more standard trial. Though both are attorneys, their roles were very different. Powell, flashy and drawn to animal prints and chunky jewelry, became a household name in the weeks after the election because she often spoke to the press about the election scheme, though her role seems to have been mostly lower-level and operational. Chesebro, by contrast, was little known and had no public profile but worked closely with John Eastman and other lawyers on the broad contours of the paperwork coup.

Removing Powell will narrow the Chesebro trial, which could help prosecutors, but it may also satisfy Chesebro, whose attorneys wanted the cases separated. “There has never been any direct contact or communication between Mr. Chesebro and Ms. Powell,” they argued in a filing last month. “Similarly, there is no correlation or overlap between the overt acts or the substantive charges associated with Mr. Chesebro and Ms. Powell.” (Chesebro rejected a deal that would have spared him prison time but required him to plead guilty to a felony and testify, ABC News reports.)

Second, Powell’s plea moves forward the Coffee County portion of the racketeering case. According to prosecutors, the conspirators arranged to unlawfully access and copy data from voting machines in the Southeastern Georgia location. Powell is the second person to plead guilty to involvement there, following Scott Hall, an Atlanta bail bondsman who copped a plea in September. Their testimony may help prosecutors target Jeff Clark, a little-known Justice Department official who attempted to lead a coup inside the department, getting Trump to appoint him acting attorney general, and to convince state legislatures to overturn election results. (He has pleaded not guilty.)

“The person in the gravest of danger [now] is Jeff Clark,” Kreis said. “Now we have a direct chain of individuals who can link Sidney Powell to Scott Hall and Scott Hall to Jeff Clark. Now there’s two witnesses who can presumably talk about the way in which Jeff Clark was not just concocting letters in his office to encourage the general assembly to overturn the election but was involved in and linked to unlawful actions in Georgia.”

Third is the question of how other people accused in the case might react to Powell’s plea. Prosecutors likely hope that it might convince some of the lower-level defendants to conclude that their chances of beating the rap are low but also that cooperating now might produce favorable terms. Agreements to testify would, in turn, presumably make it easier to mount a successful case against the biggest names in the case—Trump, of course, as well as the attorneys Eastman and Rudy Giuliani, and former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. A trial for these defendants likely won’t occur until next year.

“It’s a real prisoner’s dilemma,” Kreis said. “Who’s talking; who’s doing what; what’s the deal I’m going to get? It’s a complicated set of game theory.”

How all of the remaining defendants, with all of their different interests, choose to play will help determine what sort of game is being played: Powell’s conviction could be the first domino in a dramatic cascade, or simply an early piece taken off the board in a long, grueling chess match.