In a quiet cul-de-sac in Castlecrag on Sydney’s North Shore, the Fishwick house by Walter Burley Griffin is approaching a century of occupation.

Emerging from the sandstone ridge like a medieval rampart – stepped around boulders, blended into the landscape with natural bush gardens – it looks impenetrable, yet intriguing. As the street name, The Citadel, suggests, the escarpment on which the houses sits enjoys a commanding outlook over bush headlands, Middle Harbour and, in the distance, the Pacific Ocean. With its flat roofs and walls built largely from sandstone quarried on site, the house offers a series of spatial experiences orchestrated through controlled volume, ceiling height, natural light and outlooks.

An exemplar of Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin’s vision for an architecture in harmony with nature, it was built in 1929 for Englishman Thomas Fishwick, the local manager for Leeds-based firm Fowler & Co, which produced heavy steam-driven machinery for agriculture and road-making. Fishwick was the kind of client Griffin had in the USA, but lacked here — technically minded, interested in innovation, and wealthy.

The entry has low ceilings and concrete columns that evoke eucalyptus trunks.

Image: Tamara Graham

A tunnel cut into bedrock off the street leads into the entrance hall, the house’s second largest room, where a low ceiling rests on concrete columns stippled in green and gold to evoke the eucalyptus trunk. From here, the living area unfurls past a “see-through” fireplace to a window precisely framing views down to Sailors Bay and Middle Harbour. Professor James Weirick, a Griffin scholar, has described this progression from enclosed space to open vista as “one of the magical experiences of Griffin’s Castlecrag.” The L-shaped room includes a grand dining room and a compact kitchen of many parts that adjoins a private courtyard garden.

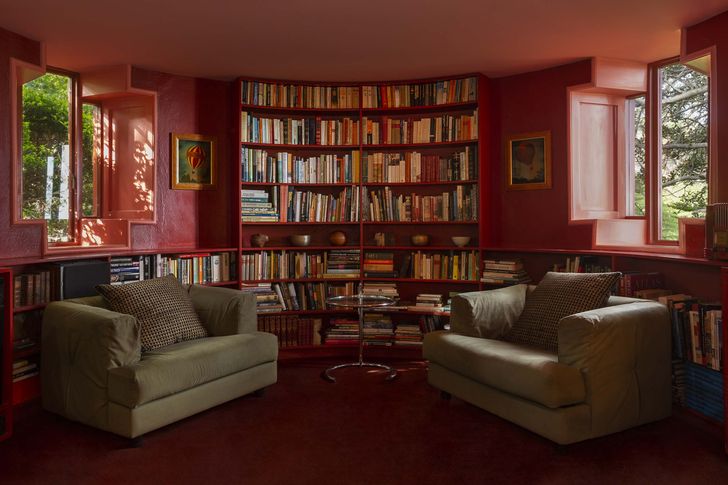

To the left of the entrance hall is a sunken study, painted carmine red, with bookshelves built into the semi-circular wall where light enters through deep, cruciform windows.

Directly above the study is the main bedroom, where the semi-circular row of north-facing casement windows feature Griffin’s signature angled glazing bars. Also on the first floor were secondary bedrooms, bathroom, and the maid’s quarters with private garden entry. As with many local Griffin houses, the Fishwick house utilized its large, flat roof as balcony with breathtaking 270-degree harbour views.

Casement windows in the semi-circular main bedroom feature Griffin’s signature angled glazing bars.

Image: Tamara Graham

Among the home’s many innovations were its split-level, open-plan living area; three purpose-built booths planned for the telephone, vacuum cleaner and radio (ultimately these were not built); built-in wardrobes in the bedrooms; an ensuite bathroom; undercover garage carved into the rock escarpment; a see-through fireplace (a stone fireplace with a glazed void above); and glass-bottomed fish ponds in the dining room ceiling. The latter were replaced in the 1930s with skylights. Each of the home’s four fireplaces has a signature riddle, from cantilevered canopies (in the bedrooms) to a glass window where the chimney should be (in the living room).

Fishwick occupied the house for just two years before work took him to South Africa. He leased his home to Nisson Leonard-Kanevsky, a Russian emigré who’d commissioned Griffin (with Eric Nicholls) to design the Willoughby Incinerator, among others, during the Great Depression. Leonard-Kanevsky left the house in 1940 and it was then leased to Rawson Deans, the brother of the Griffins’ company secretary, and his wife Nancy. The Deanses bought the house from Fishwick in 1945; in 1976, after Rawson’s death, Nancy sold it to Sue and Andrew Kirk.

Deep cruciform windows let natural light into the study, which has been painted carmine red.

Image: Tamara Graham

“We had been living in Chicago, quite near the Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright; that got us interested in architecture,” says Andrew. By coincidence (or perhaps not, given the social links that connect all of the house’s owners) Nancy had once taught Andrew French at school.

“There have never been strangers living in this house. Every occupant has either had a connection to the Griffins or a former resident,” notes Andrew.

Despite the house’s poor condition, the Kirks took on the Fishwick house on returning to Australia. They first implemented urgent repairs, followed by a full-scale restoration, completed in 1998 under the guidance of heritage architects Tropman and Tropman.

“My mother cried when she first saw the house, it was in such a bad state, but right from the beginning we felt it had a presence. It didn’t really look good, but it had a calming effect. Something about the stone walls, perhaps,” says Sue.

Although it was structurally unaltered, the house suffered severe damp and leaked profusely. There were unsympathetic add-ons, and its embedded electrical circuitry and concrete reinforcement had rusted out. The kitchen was degraded and some of the interior stonework crumbling. Outside, the signature Griffin bush gardens were overrun with exotic species and weeds.

Unlike many other Griffin houses, most of the house’s decorative glass, brass hardware, timberwork and ceramic tiles remained intact. Most of the external timber doors and windows had rotted and were replaced in the restoration while the Kirks’ renewal of the compact kitchen followed the original layout and material philosophy, using timber cabinetry, cork flooring and brass hardware.

Tall glazed timber doors line the sunken study near the foyer.

Image: Tamara Graham

The entrance hall’s eight concrete columns, once elaborately marbled with layers of translucent coloured glaze then heavily stippled with gold pigment, had degraded over time and been repainted. However, meticulous work uncovered three in reasonable condition, which guided the restoration of all to their former glory.

Considered to be the finest and most intact surviving Griffin residence in Australia, the Fishwick house has been widely documented in print and on film. It is protected by all three levels of Australian government, with listings on the Register of the National Estate, the NSW State Heritage Register and Willoughby Council’s Griffin Conservation Area of Castlecrag. Of the 13 remaining Griffin houses built in Castlecrag (from an estimated 70 that were designed), this is the largest and the only two-storey residence among them. The rest are single-level, many modestly built as speculative or demonstration homes.

Walter and Marion Mahony Griffin shared a love of nature and had been powerful figures in the Prairie School, a North American strand of modernism, influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright, with whom both Walter and Marion had worked in Chicago, Marion as one of the first registered woman architects in America. She was a driving force in much of the Griffins’ work, and artist of the watercolour illustrations that won the competition to design a national capital for Australia in 1912.

Following their success in the competition, Walter and Marion moved to Australia in 1913, but they had left Canberra by 1920, frustrated at the political interference with their vision for the “garden city.” They moved to Melbourne and continued in private practice, designing buildings and taking town planning commissions, before moving again to Sydney. To demonstrate their theories of suburbs co-existing with nature, they formed a development company and acquired 263 hectares of Sydney bushland, including 6.44 kilometres of water frontage from Castlecrag to Castle Cove.

The Griffins’ masterplan called for homes that were linked by pathways and public reserves to foster connection with the bush.

Image: Tamara Graham

The Castlecrag estate was to be the Griffins’ utopia: a masterplanned suburb where homes with no boundary fences nestled into escarpments and ridges, linked by pathways and public reserves to foster community and connection with the bushland hugging the Sydney harbour foreshore. It was revolutionary then, and it remains a protected place of international significance today.

Today, in Castlecrag, the Kirks are at a crossroads. Having loved this house back to life over more than 40 years, they are preparing for a new chapter; it’s time, they say, to let go. “We’ll be very sad to leave. You can’t replace a home like this. But the house needs someone who can give it the attention and care that we no longer can,” Sue says.

Having devoted themselves to its conservation and legacy, and tirelessly worked with the Griffin Society to share their home with the public, they will leave the house in impeccable condition, possibly the prime of its long life. It stands today not only as a Griffin monument, but also as a moment in time for Australia. A moment when our architecture truly diverged from the fiddly Victorian terraces and gentlemanly Georgian villas of Mother England. A time before the battle lines of suburbia were drawn across the Sydney basin, gauging out ancient sclerophyll forests for breathless rows of brick and tile. A time before the nightmare of the “Great Australia Dream.”

This house and its suburb were designed by progressive minds, who questioned the status quo of property and privilege. Nearly a hundred years later, it provokes another critical and timely question: in the context of a climate crisis, how can we live in better harmony with nature?

The entrance hall’s eight concrete columns, once elaborately marbled with layers of translucent coloured glaze then heavily stippled with gold pigment, had degraded over time and been repainted. However, meticulous work uncovered three in reasonable condition, which guided the restoration of all to their former glory.

Architect: Walter Burley Griffin Architect; Restoration (1996–98): Tropman and Tropman Architects.

Source

Project

Published online: 19 Jun 2023

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Tamara Graham

Issue

Houses, June 2023