The Seattle-based architect Michael Eliason has a number of complaints about the way America makes its apartment buildings. The components are inferior, he says: The best sliding doors and windows are made elsewhere. The designs rarely accommodate larger families. And there are too many staircases.

Too many what now? Eliason is the founder of Larch Lab and the lead evangelist of a small group of architects and developers intrigued by the possibilities of making multifamily buildings with only one stairway. And conversely, fed up with the North American standards that require most apartments to be accessible by two of them.

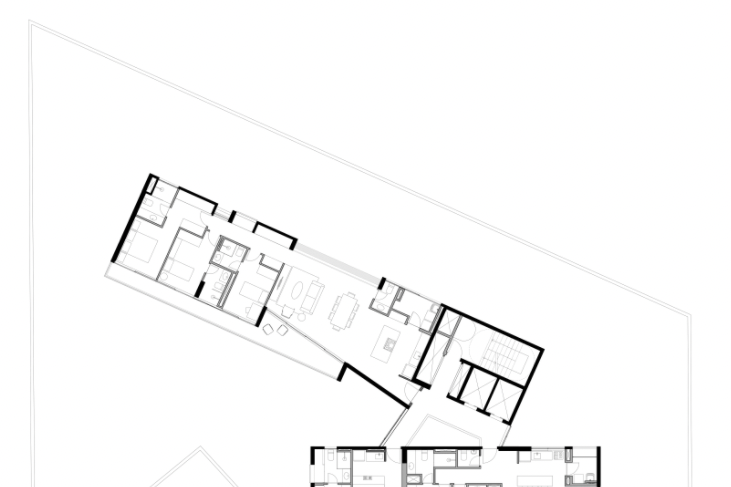

Mandating two stairways, Eliason says, produces smaller, more unpleasant, more expensive apartments in larger buildings full of wasted space. He likes to contrast the boxy North American multifamily building with nimbler designs from South Korea, China, Sweden, Italy, or Germany. In those countries, apartments in midrise buildings may be served by a single stair, often encircling or adjacent to the elevator. Online, Eliason is a founding father of what he’s called Floor Plan Twitter, where he shares these foreign, single-stair blueprints with a gusto usually reserved for imports like wine or sports cars.

Of all of Eliason’s beefs with U.S. building practices, which he has outlined for the environmental news site Treehugger, this one is both the most tangible—you don’t need to be an architect to understand the difference between two staircases and one—and the most opaque. It’s one staircase, Michael. What could it cost?

The answer, Eliason and the single-staircase brigade insist, can be measured in terms of light, air, space, and money.

Most American apartment buildings over four stories are required to include two means of egress from every apartment. In Canada, the height limit of a single-stair building is just two stories. The purported reason for such rules is fire safety, though there’s no evidence that Americans and Canadians are any safer from structure fires than our neighbors around the world, where one-staircase construction is permitted even in buildings eight, 10, or 20 stories high.

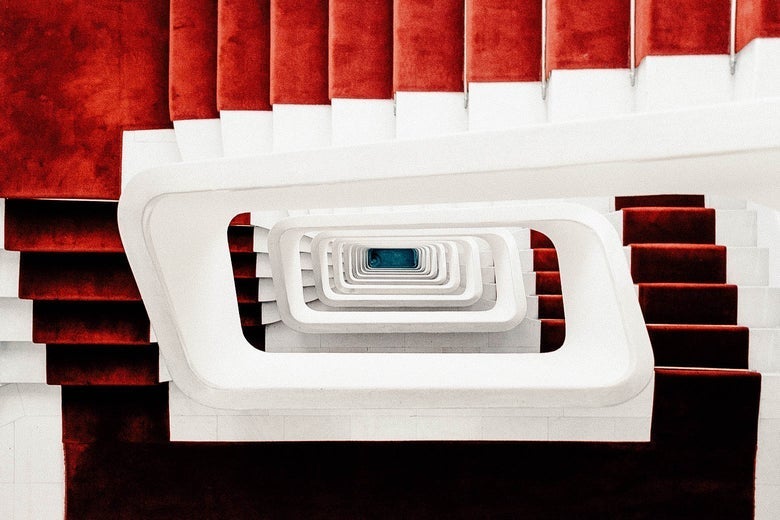

That second staircase is a drag. When we spoke last week, Eliason showed me a presentation he gives to drive home the building culture that is shaped by the two-stair system. It featured a still from the movie The Shining, of Danny riding his tricycle down the long, carpeted hallway of the Overlook Hotel. If you’ve been in an American apartment building of the past half-century or so, you probably recognize this airless environment, which architects call a “double-loaded corridor” because it has doors on both sides. Nobody likes these hallways. The double-loaded corridor, the architect Frank Zimmerman writes, is a “case study in anti-human engineering.”

Eliason observes that when you require every apartment to connect to two staircases, you all but ensure those units are built around one long double-loaded corridor, to give all residents access to both stairways. You tilt the scales in favor of larger floor plates in bigger buildings, because developers need to find room for two stairways, and connect them—and then compensate for the unsellable interior space consumed by the corridor.

The designs that result, Eliason argues, are more likely than not to offer smaller, cookie-cutter units constrained by their position along the long hallway. Apartments must look either north or south. Sunlight or shade. Sunrise or sunset. Busy street or quiet back yard. And no one, save perhaps a lucky occupant of a corner unit, gets a cross-breeze.

Cut out one of those staircases, and you can cut out the corridor, too. Narrower sites are suddenly in play. Construction costs go down. The ratio of “rentable” space in a building goes up, which makes development cheaper. That in turn can translate into lower rents or more flexible designs. Two or three units a floor is suddenly more economical, which makes the stairway a more intimate, closely shared space. Family-size units. Units where the living room faces south to the sun and the street and the bedrooms face north to the quiet shade. “In the architecture world it’s hammered in from the beginning that we need two exits from every space,” Eliason said. “But in most other countries, that second means of egress is the fire brigade.”

Another Floor Plan Twitter fan is Conrad Speckert, an architecture student at McGill University who takes that required second staircase personally. “I grew up in a three-storey, single egress apartment building where we knew our neighbours well, the stair landings were generous and naturally lit, and everyone got pretty crazy with their Christmas decorations,” he writes on the website for his master’s degree project, Second Egress. “My childhood home in Switzerland reminds me that stairs should be about more than just circulation and fire safety, and that there is a sensuality to them too—the tactile sensation of a winding guardrail, the slip-resistance of the treads, the wash of light from a skylight or the breeze from an operable window.” (The classic European single-stair also produces a mean movie fight-scene.)

But such buildings have been illegal in Canada since 1941, when the country adopted stricter building regulations. For Speckert, the Second Egress website is the first step toward petitioning for a change to the Canadian building code. He has collected the maximum heights of single-stair buildings in various countries and assembled a “Manual of Illegal Floor Plans” from more permissive regimes, showing what might be possible.

In North America, staircases are usually required to be closed off from the corridor, which makes them into isolated and unpleasant spaces. They’re also designed that way. But they don’t need to be. “There’s an intuition that once a building is more than two stories of height, you use the elevator,” Speckert told me. “But when you have a building with one stair that opens directly to the landing, you have the opportunity to design that stair. To not make it concrete with an aluminum guardrail. Now you’re sharing circulation with neighbors, you may know them.”

But the biggest problem with two staircases, the single-stair brigade agrees, is affordability: A second staircase makes it harder to build small-footprint, midrise, multifamily rental buildings. It is one of the many obstacles (zoning, parking, height limits, etc.) we have thrown up over the past century to block the “missing middle” housing that defined early 20th century cities, and now constitutes some of their most beloved and expensive real estate.

The specter of big structure fires—like the fire at London’s Grenfell Tower, the single-stair housing project whose defective façade panels caught fire in 2017, killing 71 people—is what reformers like Eliason and Speckert are up against. But building fires are much less common than they were when single-stair rules were codified, to the extent that most city dwellers roll their eyes at office fire drills and curse their hyperactive apartment smoke alarms. Data from the World Fire Statistics Centre show Canada, for example, has little to show for its two-story limit.

Bobby Fijan, a developer in Philadelphia, is another guy who likes a single stair. Fijan calls himself the Bill James of floor plans, a reference to the baseball analyst whose keen statistical-appraisal technique helped changed the way players and skills were valued in the sport. “I’m not sure the effect it would have on a 250-unit building by Mill Creek,” he said, citing a large apartment developer. “But it would be particularly meaningful on urban infill”—the one-off apartment projects taken on by developers in already dense neighborhoods.

“I’m having to do increasingly convoluted ‘stacked townhouse’ arrangements instead of small-flat buildings,” said the developer Payton Chung. He’s putting the top floors of a small building inside one multistory apartment, rather than making them separate apartments, to avoid triggering that second-stair requirement. The International Building Code (which, like the World Series, is really an American institution) doesn’t care if you have six or 60 units on a floor—you still need your two staircases.

One place that’s closer to the global standard? Eliason’s hometown of Seattle. The city has approved single stairs in buildings up to six stories. It’s all right with the Seattle Fire Department. Could it work in your city, too?