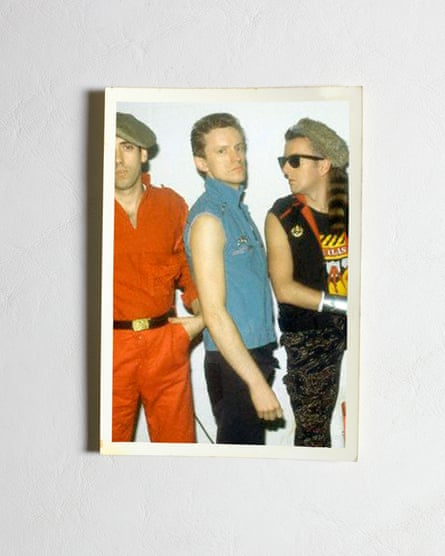

Ausaf Abbas, 55

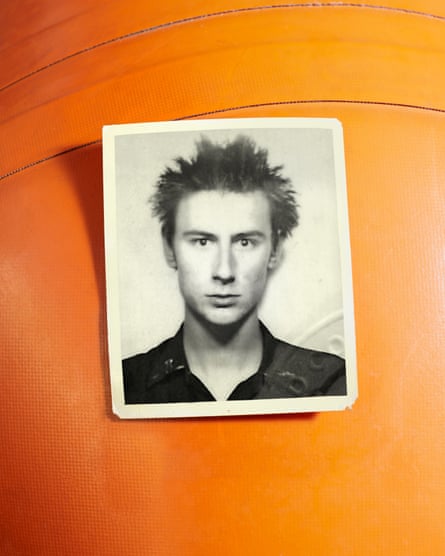

Then: bass player, Alien Kulture

Now: investment banker

We very much believed in the philosophy of punk – here’s a chord, here’s a second, here’s a third, now go and form a band. I’d never touched a bass guitar until our first rehearsal, but that didn’t matter. It was all about the energy and the enthusiasm.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

We were probably from the more intellectual wing of punk and were very much involved in the Rock Against Racism campaign. Our name came from Margaret Thatcher, who’d made an infamous comment about how Britain was in danger of being swamped by an alien culture. We interpreted that to mean that if you weren’t white, Anglo-Saxon, middle-class, Protestant, maybe you didn’t fit in.

The reason we split up was quite classic. The drummer and I were both students at the London School of Economics. We had our finals coming up, but got an offer of a 20-gig tour with another band. Our singer insists it was The Specials, but I’m not so sure. However, our Pakistani roots reasserted themselves and we decided we’d better concentrate on passing our finals.

I loved what the band did, but I knew I wasn’t going to make a living from it. After getting my masters degree, I started working for BP as an economist. I didn’t know much about finance – it was quite an arcane, closed industry – but when Thatcher liberalised and deregulated large parts of the British economy, she set off a revolution in financial services. It seemed an obvious move to make, from oil into finance, so I joined Merrill Lynch, where I spent 21 years.

I’m sure my 20-year-old self would look at me and shout, 'Sellout!'

The money I earn does allow me to do some good – one of my friends worked for Amnesty International and knew I was an investment banker. He called me up and said, “Hi. I need you to send me £1,000, otherwise 12 people will die in Colombia tomorrow.” I agreed immediately. I stumbled into investment banking by chance, but I love the opportunities it has given me. I’ve met prime ministers and finance ministers and CEOs of major corporations. This was unbelievable for an immigrant kid who grew up in Brixton in a single-parent family.

I’m sure my 20-year-old self would look at me and shout, “Sellout!” But I don’t feel like a sellout. I’m just older and wiser. I’m 55 now. I’m old, fat and bald. When I tell people I was in a punk band, most just laugh and think I’m joking. But I’m very proud of what we did. In our own way, we helped Asian kids stand up and be counted for the first time in this country. Why wouldn’t you be proud of that?

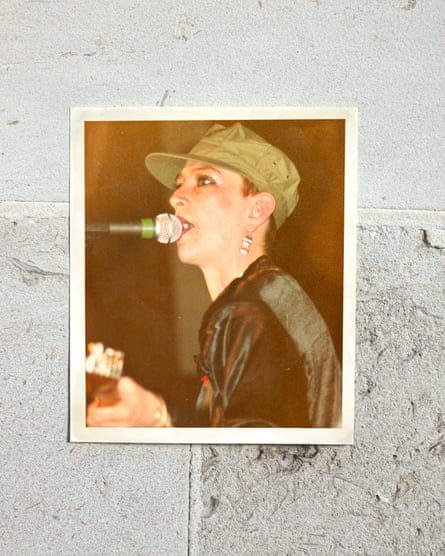

Lesley Woods, 56

Then: singer/guitarist, Au Pairs

Now: barrister

I was a late starter. Punk had been around quite a while when I got into it, in 1978. What was really appealing was sticking two fingers up at rock musicians. People could get up and do their thing without having to be these great, macho lead guitarists. And women could do it on their own terms, without having to conform to some female stereotype of having big boobs and being really pretty. People like Siouxsie Sioux, Poly Styrene and Patti Smith were great role models.

But we were constantly met with a wall of violence and aggression. There were fights; [Slits singer] Ari Up got stabbed. There comes a point where you can’t go on any more at that level. After the band folded, my brain was quite scrambled and I needed to get my mind back, so I thought I’d do something really difficult and started studying law.

I was called to the bar when I was 32. I started off doing asylum law, working with refugees, which tallied with my political values. Although it was heartbreaking a lot of the time, when you won a case, you came out and yelped for joy. You knew you’d made a difference. I do very little asylum law now, but I still work in immigration. I’ve always had a very strong sense of justice, and working in this area means I haven’t had to compromise my integrity.

Women could do it on their own terms, without having to conform to some female stereotype of having big boobs

People were aware of my past and it probably put a lot of the more straight people off. When I first came to the bar in 1992, women couldn’t wear trousers, which gives you an idea of how backward it was.

I still muck about with music, but I wished I’d paid more heed to that particular itch about five or 10 years ago. My work is so intense that it’s hard to fit music in now. I’ve been making new recordings and I still do the odd performance. I’d love to do some collaborations, though. It’s a bit lonely doing it on your own.

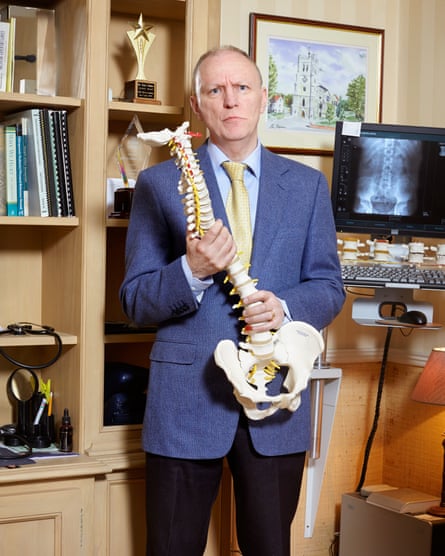

Terry Chimes, 59

Then: drummer, The Clash

Now: chiropractor

I just wanted to be in a band, and this was the most exciting band I could find. Everyone else in The Clash was angry at the world and the establishment. I wasn’t. That’s why I left, actually. I felt like the odd one out.

As a child, I wanted to be a doctor, but I also wanted to be a musician; it’s kind of hard to be both. The part of me that wanted to be a musician won that particular battle – you have to do music when you’re young. But by the time I’d done it for 15 years [playing with Black Sabbath and Hanoi Rocks as well as The Clash], I was craving working in medicine more and more, so I made the big jump. In 1988, at 32, I stopped music and spent five years studying full-time. My musical peers weren’t that surprised. The Clash’s manager Bernie Rhodes once said, “You’re like some young doctor. I can imagine you saying, ‘Here are your pills, madam.’” I don’t know where he got that from, but he’d spotted something.

During my time in music, I saw how people’s health was determined by their lifestyle. I had a strong urge to heal people. I’ve now seen more than 45,000 patients, so I’ve made a lot of people better. If you don’t like people, then it’s the job from hell. I treat a lot of musicians. They say, “I’d rather come to you. You’re a musician and you understand what I do.” Some patients are interested in music and like to have a chat about it, but most just say, “I’m in agony. Can you please get rid of it?”

Everyone else in The Clash was angry at the world and the establishment. I wasn’t. That’s why I left

The experience of challenging and changing the establishment was good for everyone at the time. Whatever you do after that you bring that with you: the sense that things don’t have to be the way they are. I have another life now, standing up against massive corporations that want to ruin everyone’s health and make money out of it, whether with genetically-modified food, sugar-laden rubbish or drugs we don’t really need.

People say to me, “Don’t you miss playing in front of 70,000 people?” Well, I’ll probably see 70,000 patients before I die. Getting people well and making them happy: I don’t think I’ll ever want to stop doing that.

The Strange Case Of Dr Terry And Mr Chimes by Terry Chimes is published by John Blake at £9.99.

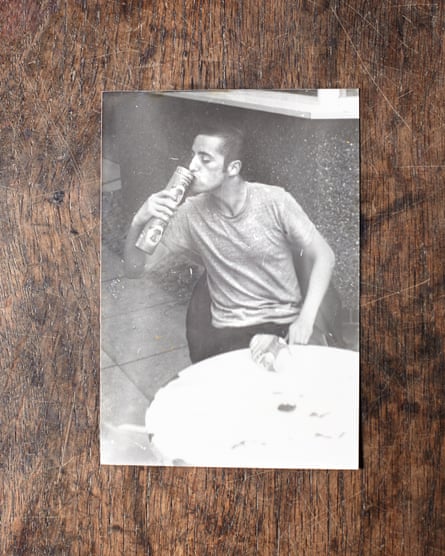

David O’Brien, 54

Then: part of Manchester’s punk scene

Now: vicar

As a teenager, I dropped in and out of jobs in factories and supermarkets without having much direction, but punk gave me an energy. I wasn’t an anarchist. I wanted society to stop and think about an alternative idea. Plus, I felt comfortable in Doc Martens boots and bleached jeans.

I was an illegitimate child. My dad was an alcoholic whom I hadn’t seen since I was four and my mother was a single parent who had eight kids, although she lost two of them. She brought the six of us up by herself.

Growing up, Christianity was irrelevant to me. I used to drink too much and get in trouble at football matches. The closest I got to worship was standing at the Stretford End on a Saturday at Old Trafford.

I thought church was for nice, middle-aged people like Thora Hird. I remember carol singers coming into the pub one Christmas and, like everyone else, I was drunk and barracking them. One day, when I was on the dole and had just got my giro, me and my mate went to the pub until we got chucked out – at 3pm in those days. We were walking through some woods when we saw an occult sign cut out of the ground; the rumour was that a coven was using it for black magic. I’d had a bit to drink, so I jumped into the middle to see what happened.

When you put on a dog collar, people assume you’ve had no life before

I didn’t feel right afterwards. It frightened me and got the cogs turning with the question: what if there is something else out there? So I picked up a copy of the New Testament that had been on the shelf for years, collecting dust, and I felt better after reading it. It still took me three years to get inside an actual church.

I had this nagging thought for the next 10 years: “Become a minister. Become a minister.” So I enrolled on a one-year foundation course in theology, then completed a degree in applied theology. Five and a half years ago, I came down to Shrewsbury and became a fully-fledged vicar.

When you put on a dog collar, people assume you’ve had no life before. But the passions that got me into punk are still there, and that’s what I bring into ministry now. It’s about a desire for meaning.

I haven’t got my vinyl any more, but I still listen to one or two things on YouTube. It’s a reminder of where I’ve come from.

David O’Brien’s book Northern Soul: Football, Punk, Jesus is published by Onwards and Upwards at £8.99.

Steve Ignorant, 58

Then: lead singer, Crass

Now: lifeboatman

Punk had a purpose. Every gig would benefit something: a rape crisis centre, a donkey sanctuary, an old people’s home. It was positive. We wanted a nice world to live in. Only, this time, we weren’t asking – we were telling.

From 1977 to 1984, I was the lead vocalist for Crass. We toured the UK, playing gigs wherever and whenever we could. When Crass finished, I continued to perform and record with Conflict and later formed the bands Schwartzeneggar and Stratford Mercenaries.

In 2007, I moved to Norfolk with the intention of living quietly by the coast. I was going to sweep up leaves and all that sort of stuff – but it wasn’t to be. The year I moved, I got an offer to do two nights at Shepherd’s Bush Empire. With every gig I do, I like to donate to a cause. I knew the independent lifeboat service in Sea Palling is always desperate for funds, so I thought that was ideal: I could see where the money actually goes. They got about £1,000 and bought new life jackets that went on to save people’s lives.

The crew took me out on the boat, dressed me up in a drysuit, threw me overboard and picked me up, then asked, “So, what about joining?”

At first, I was very reluctant – I worried about the commitment and imagined that I would have to go on parade. The idea of some bloke looking me up and down and telling me off for not shaving properly went totally against my principles. But they were all scruffier than me. Now I’m a full-time member.

Being part of the crew is similar to being in a band. You’re full of adrenaline when you’re on stage, but the worst thing that can happen is that you forget the words or the lead guitarist plays a bum note. It’s not the same adrenaline when you’re suddenly out at sea and pulling someone from the water. It affects different people in different ways. It doesn’t hit me at first, but about an hour later, it’s as if I’ve taken amphetamines. I can’t shut up about it.

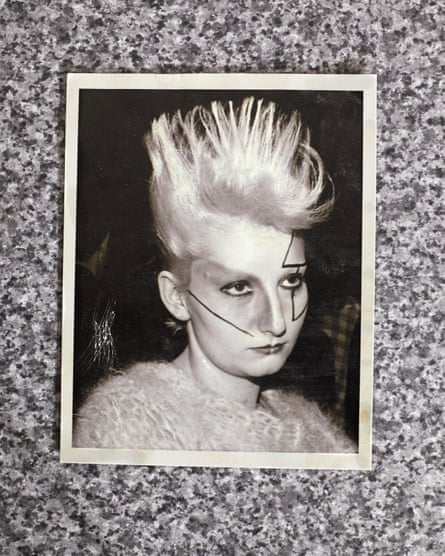

Jordan, 60

Then: punk style icon

Now: veterinary nurse

People said, “You must be so brave, looking like that out in the street.” I’d often wear a mohair jumper with suspenders and stockings and see-through knickers. It was nothing to do with bravery. Quite the opposite. It was about feeling comfortable and at one with yourself. I always liked dressing my own way. When I came up to London to try to get a job at Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s shop, Sex, I was already wearing the stuff they were selling – I had just cobbled it together myself. But there wasn’t a job available straight away, so in the meantime I went to work in Harrods with green makeup on.

I eventually worked right at the forefront of punk with Vivienne and Malcolm. I styled the Sex Pistols – messing up their clothes. I appeared on stage with them, including on their first TV appearance on Granada’s So It Goes, to lend weight to their performance fashion-wise. I also managed Adam And The Ants during their punk era.

A lot of the major music moguls were extremely sexist. An A&R guy once said to my face, “This is not a woman’s job. You should be cooking and laying on your back.” I didn’t want to be there any more, so I came home to Seaford.

I wanted to work in something meaningful, so I got a job at my local vet’s. I’ve now been there for 22 years. It’s not pushing bits of paper around. It’s a real job where you can make a difference to how animals are cared for. Punk showed me you could be whatever you wanted to be, and that’s the way I’ve lived my life. I haven’t changed.

It was nothing to do with bravery. Quite the opposite. It was about feeling comfortable and at one with yourself

A lot of my old teachers still live locally and bring their animals in. They remember all the trouble I got in at school. I had a row with my headmaster. He said, “I can’t have you looking like this. You’ve got red and pink hair. You’ve got a mohican. They’ll all start copying you.” I told him, “No one’s going to copy me. Look at them. They’re laughing.” They made me wear a headscarf when I walked between lessons. Now these teachers say, “Oh, I always loved how you looked.” A bit of history has been rewritten.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion