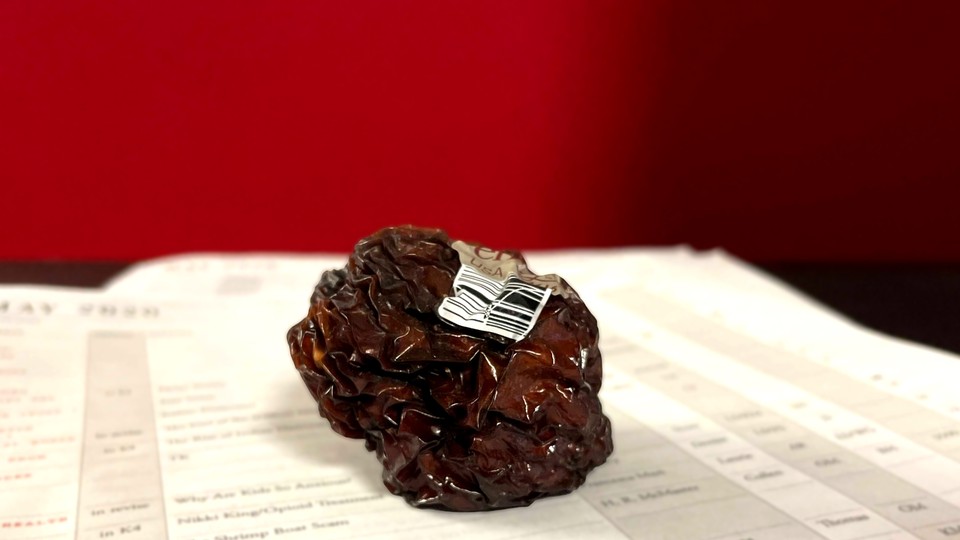

A Crumpled, Dried-Out Relic of the Pandemic

I returned to my office and found an apple that had somehow not rotted away.

I left a lot of things at my desk in March 2020: a toothbrush, shoes, several varieties of tea, a mug full of plastic utensils, at least three jars of peanut butter. But one of my colleagues left behind a less shelf-stable treasure: one Envy apple, coquettishly perched atop a pile of fact-checking notes.

For the first few weeks of The Atlantic’s work-from-home odyssey, this colleague was curious about what had become of his apple. But as the months wore on, it slipped his mind. That is, until I visited the office one recent Monday, 438 days after we were instructed to work from home, and found it shriveled but intact—a biological marvel that most closely resembled an oversize date. The apple had not oozed. It did not stink. It was still firm to the touch and sported no visible mold. It appeared to have undergone an absolutely immaculate desiccation.

How was it possible that this ordinary fruit was not, after 14-plus months at room temperature, a puddle of putrid goo? After consulting no fewer than four experts, I learned that the apple had benefited from a combination of natural decay processes, a fortuitous lack of fungi, and the very particular environmental conditions of an abandoned, climate-controlled office. But I couldn’t get these food scientists to agree on what was, to me, the central question of this investigation: Could I taste it?

Which is exactly what the apple wanted me to ask. Once a fruit leaves its mother plant, “the main thing, as far as the fruit is concerned, is to disseminate the seed,” Anish Malladi, a pomologist at the University of Georgia, told me. Its best bet is to seduce an animal into eating it, which means remaining attractive—sweet, juicy, and colorful—for as long as possible. It needs to stay alive. “Even after the fruit is harvested, it still undergoes something called respiration. It’s breaking down sugars and releasing carbon dioxide, very similar to what we do,” Malladi said.

After exhausting its supply of easily accessible sugars, a fruit will try to cheat death by attacking its own cells to find any source of energy it can. “Then there’s all sorts of chaotic processes,” Diane Beckles, a postharvest biochemist at UC Davis, told me. Chemicals that are normally kept separate by cellular structures might suddenly come into contact and react. If a fruit’s peel is damaged before or during this decay process, fungi and other microbes can also “join the party,” Beckles said, and feast on the nutrients inside. You know the drill: If you bang up a piece of fruit and leave it out, it turns funny colors, gets squishy, gives off weird-smelling liquids, and wastes away to nothing.

The thing is, that’s not what happened to this apple, or at least not entirely what happened. Most likely, it lost too much water for these decay processes to reach their full potential. If you’ve ever eaten beef jerky or raisins, this should make intuitive sense. On a biological level, drying helps keep food from rotting, because the microbes that cause rot need moisture to survive. Ilce Medina Meza, a food engineer at Michigan State University, told me that most industrial fruit dehydration today involves blowing a lot of hot, dry air at a target, and can be done in just a couple of hours. But that’s certainly not the only way to do it. Dehydration is one of humanity’s oldest tricks for keeping food from going bad, and it can be helped along by salt, smoke, sunlight, or even a lucky combination of air temperature and moisture.

Offices, as anyone who’s ever bought a desktop humidifier knows, tend to be rather dry environments, even with their human inhabitants contributing breath, sweat, and umbrella drippings on a daily basis. So it’s not totally unreasonable that The Atlantic’s HVAC system could have dried out the apple, especially if the temperature inside the office didn’t change much during those 14 months. That would explain the shrinkage, as apples are roughly 85 percent water. According to Medina Meza, it could also help explain the apple’s rich, purple-brown hue: As the water evaporated from the apple, the compounds that give the skin its normal red-and-yellow coloring would have gotten more concentrated and appeared darker as a result. (Oxidation was also likely involved.)

So if drying is such a great way to preserve foods, and in all likelihood this apple was dried, why not eat it? Medina Meza was enthusiastic, but Jessica Cooperstone, a food scientist at Ohio State University, didn’t love the idea. “The apple in the Atlantic offices was not stored in a hyper controlled way, and for sure no one wants to eat it,” she told me in an email. Rats.

The danger: those aforementioned microbes, especially fungi. Without pathogens around, the chemical bacchanalia of cell death isn’t usually harmful—it’ll just make the fruit taste nasty—but the sorts of fungi that can infect apples are pretty much everywhere, spores a-wafting. It’s a marvel that this particular apple didn’t show any outward evidence of infection. (“I don’t see that much oozing,” Malladi noted.)

But if I was really going to eat it, I had to check beneath its shining, if wrinkly, skin. After bringing the apple home and contemplating it for 10 days (after which it still looked like a giant, moldless date), I placed it on a cutting board and sliced it in half. Inside, it was a yellow-brown color, not too dissimilar from that of regular dried apple rings, though it felt a little wetter and spongier. And I found evidence that a modest contingent of fungi had discovered the apple during its pandemic isolation—the small, greenish patches in the photo below. Bingo, I thought. That doesn’t look so bad.

Fungi tend to like warm, wet environments, so a cool, dry office with a decently filtered HVAC system could keep them somewhat at bay, Beckles said. And before it was left out, all alone in a pandemic-stricken city, the apple must have been in pretty good shape, clean and devoid of the cuts and bruises through which microbes could enter. “I would probably just think that it got a little lucky,” Malladi said.

Lucky enough for me to eat it? Malladi let me down easy: “I don’t think it would be very palatable.”

If you were going to leave a perishable snack on your desk for the duration of a pandemic, an apple would actually be a pretty good choice. “Apples are one of the longest lasting fruits that we consume,” Cooperstone told me, and even under normal circumstances, months can pass between harvest and consumption. “If someone left the apple in their office in March 2020, the apple likely originated around September 2019.”

Apples are naturally protected against water loss and microbe attacks because they have a substantial peel and are covered with a waxy cuticle. Grocery-store apples are also usually coated in an additional protective layer of artificial fruit wax. And apples’ rigid cell walls help keep them from totally collapsing once decay sets in, Beckles explained. She emphasized that the cultivar of a fruit can make a big difference: Envy apples in particular are bred to have thick skin, and they brown very slowly if they do get injured, which could have helped this specimen decay especially slowly.

In other words: So many variables had aligned to preserve this apple just so that I simply had to eat it. The apple deserved nothing less. When I first asked Beckles if I could take a bite, she put the question right back to me: “I personally couldn’t. Could you?” But after I argued on behalf of the poor abandoned fruit—it smelled just like normal dried apple rings! Some of the inside flesh wasn’t so discolored! I have only a middling instinct for self-preservation anyway!—she relented. “You can do that in the name of science,” she said.

And so I did. In fact, I got three other people to eat it with me. We cut away the rotten and oxidized bits, distributed the inchworm-size morsels that were left, and gingerly placed them in our mouths. Reviews ranged from “Pretty bitter with hints of apple flavor” to “It doesn’t taste pungent.” The skin was an afterthought, and the texture of the flesh, for the first couple of chews, was rather like that of a gummy bear; afterward, it sort of became mush. My best approximation of the flavor is that of the raisins from bottom-shelf, vegan, low-calorie rum-raisin ice cream.

After spending so much time investigating the wonders of the apple, slicing into it was almost sacrilegious. Even though I had known it for only a short while, ingesting it felt like saying goodbye to a friend, or at least a talisman. After more than a year of waiting in place for the world to become a little more vibrant, it was impossible not to feel a kinship with this plucky little fruit—crumpled, dehydrated, a little bit smelly, but alive.