From the instant he wakes up each morning, through his workday and into the night, the essence of Larry Smarr is captured by a series of numbers: a resting heart rate of 40 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/70, a stress level of 2%, weight of 87kg, 8,000 steps taken, 15 floors climbed, eight hours of sleep.

Smarr, an astrophysicist and computer scientist, could be the world’s most self-measured man. For nearly 15 years, the professor at the University of California at San Diego has been obsessed with what he describes as the most complicated subject he has ever experimented on: his own body.

Smarr keeps track of more than 150 parameters. Some he measures continuously in real-time with a wireless gadget on his belt; some, such as his weight, he logs daily; others, such as his blood and the bacteria in his intestines, he tests only about once every month. Smarr compares the way he treats his body with how people monitor and maintain their cars: “We know exactly how much gas we have, the engine temperature, how fast we are going. What I’m doing is creating a dashboard for my body.”

At 66 Smarr is the unlikely hero of a global movement among ordinary people to “quantify” themselves using wearable fitness gadgets, medical equipment, headcams, traditional lab tests and homemade contraptions, all with the goal of finding ways to optimise their bodies and minds to live longer, healthier lives – and perhaps to discover some important truth about themselves and their purpose in life.

The explosion in extreme tracking is part of a digital revolution in healthcare led by the tech visionaries who created Apple, Google, BlackBerry, Microsoft and Sun Microsystems. Using the chips, database and algorithms that powered the information revolution of the past few decades, these new billionaires now are attempting to rebuild, regenerate and reprogramme the human body.

In the aggregate data being gathered by millions of personal tracking devices are patterns that may reveal what in the diet, exercise regimen and environment contributes to disease.

Could physical activity patterns be used to inform decisions about where to place a public park and improve walkability? Could trackers find cancer clusters or contaminated waterways? A pilot project in Louisville, Kentucky, for example, uses inhalers with sensors to pinpoint asthma “hotspots”.

“As we have more and more sophisticated wearables that can continuously measure things ranging from your physical activity to your stress levels to your emotional state, we can begin to cross-correlate and understand how each aspect of our life consciously and unconsciously impacts one another,” Vinod Khosla, a co-founder of Sun Micro and investor in mobile health startups, said in an interview.

The idea that data is a turnkey to self-discovery is not new. More than 200 years ago, Benjamin Franklin was tracking 13 personal virtues in a daily journal to develop his moral character. The ubiquity of cheap technology and an attendant plethora of apps now allow a growing number of people to track the minutiae of their lives as never before.

James Norris, an entrepreneur in Oakland, California, has spent the past 15 years tracking, mapping and analysing his “firsts” — from his first kiss to the first time he saw fireworks on the Mall in Washington DC. Laurie Frick, an Austin, Texas, artist, is turning her sleep and movement patterns into colourful visualisations made of laser-cut paper and wood. And Nicholas Felton, a Brooklyn data scientist, has been publishing an annual report about every Twitter, Facebook, email and text message he sends. More than 30,300 follow his life on Twitter.

Most extreme are “life-loggers”, who wear cameras day and night, jotting down every new idea and recording their daily activities in exacting detail. Even President Barack Obama is wearing a new Fitbit Surge, which monitors heart rate, sleep and location, on his wrist, as a March photograph revealed.

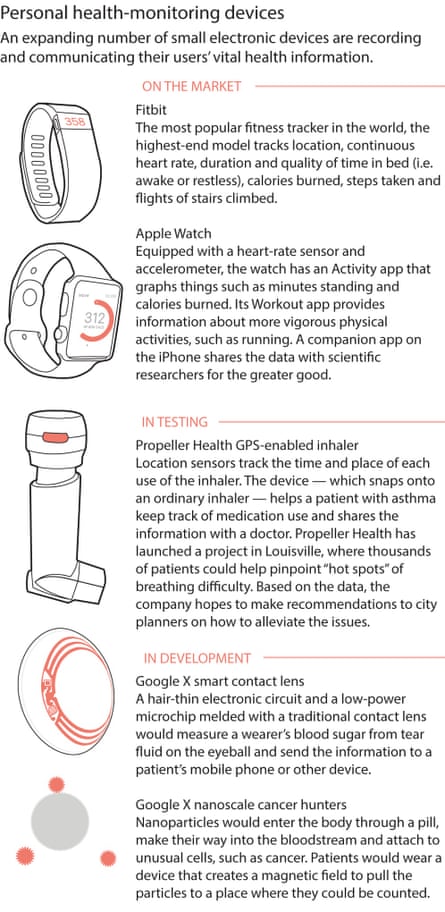

Tech firms are responding by inventing devices that can collect even more data, which the tech titans foresee as the real gold mine. At the Consumer Electronics Show in January in Las Vegas, new gizmos on display included a baby bottle that measures nutritional intake, a band that measures how high you jump and “smart” clothing connected to smoke detectors. Google is working on a smart contact lens that can continuously measure a person’s glucose levels in their tears. The Apple Watch has a heart-rate sensor and quantifies when you move, exercise or stand. The company also has filed a patent to upgrade its earbuds to measure blood oxygen and temperature.

In the near future, companies plan trackers that will measure from the inside out – using chips that are ingestible or float in the bloodstream.

Some physicians, academics and ethicists criticise tracking as prime evidence of the narcissism of the technological age – and one that raises serious questions about the accuracy and privacy of the health data collected, who owns it and how it should be used. There are also worries about the implications for broader surveillance by governments, such as what happened in the US with mobile phone providers and the National Security Agency.

Critics point to the brouhaha in 2011, when some owners of Fitbit exercise sensors noticed that their sexual activity – including information about the duration of an episode and whether it was “passive, light effort” or “active and vigorous” – was being publicly shared by default.

They also worry that wearables will be used as “black boxes” in legal matters. Three years ago, after a San Francisco cyclist struck and killed a 71-year-old pedestrian, prosecutors obtained his data from Strava, a GPS-enabled fitness tracker, to show he had been speeding and blew through several stop signs before the accident. More recently, a law firm in Calgary, Alberta, is trying to use Fitbit data as evidence of injuries a client sustained in a car crash.

More sophisticated tools in development, such as an app that analyses a bipolar person’s voice to predict a manic episode and injectables and implants that test blood, offer greater medical benefit but also pose greater risks. Des Spence, a Glasgow general practitioner, argued that unnecessary monitoring is creating anxiety among tracker-wearers. “Health and fitness have become the new social currency, spawning a ‘worried well’ generation,” he wrote in the April issue of BMJ, the former British Medical Journal. “Getting the data is much easier than making it useful,” said Deborah Estrin, a professor of computer science and public health at Cornell University in New York. Constantly measuring one’s heart rate may be helpful for someone heavily involved in sports or at risk of a heart attack. “But it’s unclear how important and meaningful it is for the everyday person,” she said.

Estrin and other experts argue homo sapiens have survived for about 130,000 years without such technology because the human body already has a number of built-in alarm systems. Any mother who has been woken by a crying child knows a gentle press of the back of the wrist to a forehead is fast, free and eerily accurate in diagnosing a fever.

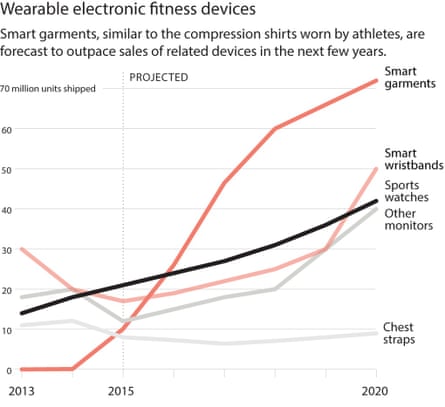

Until three years ago it was nearly impossible for ordinary people to get a read-out about the state of their bodies. Now dozens of wearable technologies with names such as the Fitbit Surge, Misfit Shine and Jawbone UP have exploited the miniaturisation of computer components and the ubiquity of smartphones to create an industry that is expected to reach $50bn in sales by 2018, according to an estimate by Credit Suisse.

The research firm Gartner forecasts that 68.1m wearable devices will be shipped this year. A growing percentage are being purchased by employers, including Bates College in Maine and IBM, as perks for their workers. A survey by Nielsen last year indicated that 61% of those aware of wearable technology for tracking and monitoring medical conditions use fitness bands.

In March, when Apple announced its ResearchKit initiative to allow people to share the information from their apps with researchers working on projects in asthma, heart disease, diabetes, breast cancer and Parkinson’s, more than 41,000 people volunteered within the first five days.

But it’s unclear whether young adults’ open attitude toward sharing their data will remain when the next generation of more invasive trackers becomes commonplace.

Ginger.io, which was developed by data scientists from MIT, has created an app that can alert a mental health provider to the possibility of depression or a manic episode – based on how much a patient moves around or how many people they talk to that day. Silicon Valley-based Proteus Digital Health has developed a prototype of a chip the size of a grain of sand that can be embedded in a pill. When the pill is swallowed, the chip sends a signal that’s logged on to central servers that you can access on your phone or desktop.

The life sciences unit of Google X, the search company’s secretive research lab, is working on building a nano-size particle that will travel in the bloodstream. The particles would circulate throughout the body and attach to particular types of cells, such as cancer cells, or to enzymes given off by plaque in the arteries before they are about to rupture or cause a heart attack or stroke. If the particles found questionable cells or enzymes, they would send a signal to a device worn outside the body that would transmit the information to the patient or to a physician.

The innovation is outpacing the scientific and legal framework for testing and regulating such devices. The US Food and Drug Administration in January indicated it would regulate devices that are invasive but take a lighter touch on wearables.

According to the agency’s draft guidelines, a product crosses into the territory of a medical device, which requires a rigorous and expensive FDA review, when its intended use refers to a specific disease or condition, or it presents an inherent risk to a user’s safety. That would essentially leave hundreds, if not thousands, of “low-risk general wellness” products – a category that presumably applies to the current incarnation of Fitbits – free from extra scrutiny.

In the US they would still be subject to monitoring by the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which has the power to recall products to protect the public from risk of injury or death. How the data that is generated from the devices is protected and shared is murky. In the US patient privacy rules don’t apply to most of the information the gadgets are tracking. Unless the data is being used by a physician to treat a patient, the companies that help track a person’s information aren’t bound by the same confidentiality, notification and security requirements as a doctor’s office or hospital.

That means the data could theoretically be made available for sale to marketers, and eventually be worth billions to private companies that might not make the huge data sets free and open to publicly funded researchers.

Larry Smarr’s journey into the data of his life began when he moved to California in 2000.

“I had spent 28 years in the heartland of the obesity epidemic in Illinois. I had gained a lot of weight and wasn’t exercising. I got to La Jolla and looked around and said, ‘Oh, my God, if I don’t get with the programme, they are going to send me back,’” he recalled.

Smarr came to California as a computer science professor to head a $400m multidisciplinary research institute for the University of California that has been called the West Coast equivalent of MIT’s famous Media Lab. Composed of scientists, artists and technologists, Calit2 (or the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology) aims to rapidly develop prototypes of technological innovations and test them in the real world.

Embracing the institute’s multidisciplinary philosophy, Smarr took a scientist’s approach to investigating himself. Although he had no previous experience in medicine, nutrition or biochemistry, he trained himself, he said, by reading more than 600 journal articles on monitoring and health.

He measured his way to lifestyle change: no coffee after 10am, because he tested how long the effects lasted after his last drop; 40 minutes on the elliptical, because that was how long it took for him to reach his optimal heart rate; new vitamin supplements every few months, as dictated by his evaluation of his blood work.

“We are in a once-a-century period of discovery about the human organism,” Smarr said. Quoting science fiction author William Gibson, he said “the future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed”.

Smarr’s mantra is that these devices and tests will help people take personal responsibility for their own health. And an increasing body of behavioural medical research has found that patients who track their diet, physical activity and weight achieve better results than those who don’t, suggesting that wearable monitors provide feedback that reinforces personal accountability.

“The mythology in this country is you can do whatever you want to your body, and a doctor will give you a pill to fix it,” Smarr says. “That needs to change.” Few people may be willing to go as far as Smarr. In 2009, when blood tests showed he was secreting excessive amounts of something called C-reactive protein, a substance found in blood plasma that is a marker of inflammation, he took the results to his internist: “There’s something terrible going on.” The doctor asked how he felt. “Fine,” said Smarr, and so the doctor laughed and sent him home, he recalled.

“This is when I began to realise there is a disconnect between science and medicine,” said Smarr, who countered by writing down how he was feeling in a diary. “I realised I could data-mine this information,” he said, on a spreadsheet with a scale for the severity of issue. He was surprised at all the things he had dismissed as minor: blurriness and stinging in his eyes for a short while – “like you touched jalapeño” – arthritis, swelling in his belly. The record-keeping didn’t yield a diagnosis, so in 2011 he decided to try to identify the organisms in several months of stool samples. With more than 90% of the cells in the human body made up of other organisms, the idea of keeping one’s “microbiome” healthy was just taking off; Smarr was curious about how that applied to him.

“You are an ecology, and the health of those bugs determine how you are,” he said. He looked at all his data and had a eureka moment: he had Crohn’s, an inflammatory bowel disease.

Last year, Smarr ventured further in his quest for self-discovery. He got an MRI of his abdomen and used a 3D printer to create a model of his own colon. But that didn’t lead to any new insights, and the model is now a paperweight on his desk.

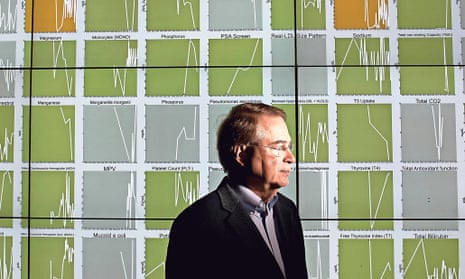

One weekday afternoon in his lab, Smarr studied his life on a 5.5m by 2.5m monitor that spans most of the room. On the board were 150 key variables about his body over a 10-year period, displayed in coloured rectangles. Most were green, meaning they fall within the expected, healthy range. But some were yellow (one to 10 times outside the healthy range), and a handful were red (10 to 100 times outside the healthy range).

According to the custom-built “future patient” program built by coders at the research centre Smarr oversees, the scientist’s body was still in attack mode for some reason.

It has been nearly three years since Smarr discovered the issue, and he’s tens of thousands of metrics down the road, but he has yet to find a way to treat it. “People overestimate what knowledge can do for you,” he said with a shrug.

This article appeared in Guardian Weekly, which incorporates material from the Washington Post

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion