Two Chicago area buildings have landed on a list side by side with the Taj Mahal, the Statue of Liberty, and the great pyramids of Egypt, along with other international icons. It’s the UNESCO World Heritage List of the most prestigious and culturally significant places in the world, including both man-made and natural sites.

Now, the list includes eight sites designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, including two buildings in the Chicago-area.

Those eight sites are: Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania; the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin; the Guggenheim Museum in New York City; Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin; Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona; Hollyhock House in Los Angeles; Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois and the Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago.

The UNESCO committee highlighted the importance of the “organic architecture” of these buildings, including characteristics Wright pioneered, like open floor plans and a blurring of boundaries between the exterior and interior of buildings. The committee also cited the buildings’ influence on modern architecture around the world.

WTTW host Geoffrey Baer highlights his favorite sites from the designation.

Finished in 1910, Robie House is widely regarded as a peak in the prairie school of architecture, a style which Wright pioneered. Wright said that his buildings in this style are “married to the ground,” and you can see what he means. There’s an emphasis on the horizontal rather than the vertical, with low eaves and flowing interior space instead of individual rooms. At the time, it contrasted directly with existing Victorian architecture, which Wright hated. You also see his style in the ribbons of windows instead of small punched window openings.

Ever the modest one, Wright called the house a “source of worldwide architectural inspiration.” And he wasn’t wrong! The building stands in Hyde Park on the campus of the University of Chicago, and recently reopened after an extensive $11 million renovation by Gunny Harboe.

If you’ve ever gone to Wright’s studio in Oak Park, you might have also stopped by this unique church. It was completed in 1908 for a Unitarian congregation – which at one time had actually included Wright’s mother.

This is not a low-slung prairie style building. The building is made entirely of reinforced concrete, which was revolutionary at the time, especially for a church. It made the building into a sort of fortress against noisy Lake Street and the general distractions of the outside world.

Like Robie House, you enter around the side and pass through low, cramped spaces before emerging into a giant, light-filled room. But there’s a reason for that. This is actually an architectural trick Wright and many other architects have used call “compression and release.” The release comes when you step into the worship area with its soaring ceiling.

The building was also recently renovated, again by Gunny Harboe.

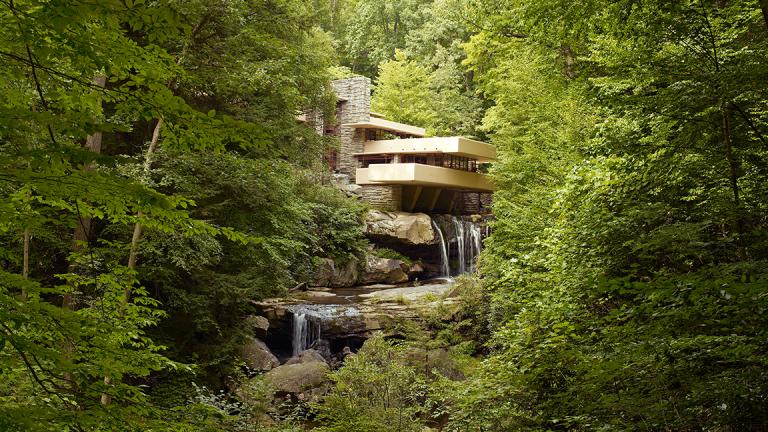

Today, Fallingwater is seen as one of Wright’s greatest accomplishments. But at the time of its completion in 1939, Wright was something of a has-been. He’d been dismissed by modernist architects, who saw Wright as stuck in the past.

The house was commissioned by Edgar Kaufmann, a Jewish department store owner who was looking for a way to gain acceptance into Pittsburgh society, which had excluded him. The house was a way for both Kaufmann and Wright to punch up their status with something spectacular.

Fallingwater was ambitiously built on top of a waterfall, and from certain angles it looks like the water is flowing right out of the building. Wright also designed crisscrossing terraces that mirror the flow of the water below. Inside, Wright’s open floor plan returns, and also features existing stones above the waterfall that protrude through the floor, so they become part of the house.

The building is a rebuttal to the “international” modernist style where the same glass box could be anywhere, completely ignoring local context. Wright’s earlier work had inspired modernism, but his buildings are each custom-made for their location. They couldn't be anywhere else. Today, we’ve returned to this idea in our contemporary notions of sustainability, low impact, and sympathy for the environment.

Wright had two compounds called Taliesin, one in Spring Green, Wisconsin and the other in Scottsdale, Arizona. He used both as his personal estates and studios, and also training centers for the next generation of architects.

We’re going to focus on Taliesin East, up in Wisconsin, and only a few hours from Chicago. The site was near and dear to Wright for both personal and professional reasons. The land was actually settled by his Welsh ancestors, and includes buildings from every decade of Wright’s career.

Taliesin was essentially a laboratory for Wright, where he could test out new ideas. He was still working on it when he died in 1959. It was also his principal residence, and parts of it had to be rebuilt after several fires.

The buildings, like much of his work, weave in and through the natural landscape. Taliesin is really the embodiment of Wright’s philosophy of living in harmony with nature. It’s also where Wright designed many of his most famous buildings, like Fallingwater and the Guggenheim Museum.

Related stories:

8 Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Added to World Heritage List

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House Reopens After Massive Renovation

Restoration of Unity Temple Revives Glory of Wright’s ‘Little Jewel Box’

Celebrating Frank Lloyd Wright’s 150th Birthday