Logging is one of the best way to keep track of what is going on inside your code while it is running. An error message can tell you details about the state of the application when an error happens. But proper logging will make it easier to see the state of the application right before the error happened or the path the data took before the error happened.

What's in this article?

- Basic overview of Python's logging system.

- Explanation of how each logging module interact with each other.

- Examples on how to use different types of logging configurations.

- Things to look out for

- Recommendations for better logging

If you want you can jump to a basic configuration example or a full fledged example used in an application.

The basics

At its simplest form a log message, in python is called a LogRecord, has a string (the message) and a level. The level can be:

CRITICAL: Any error that makes the application stop running.ERROR: General error messages.WARNING: General warning messages.INFO: General informational messages.DEBUG: Any messages needed for debugging.NOTSET: Default level used in handlers to process any of the above types of messages.

Python logging library has different modules. Not every module is necessary to start logging messages.

- Loggers: the object that implements the main logging API. We use a logger to create logging events by using the corresponding level method, e.g.

my_logger.debug("my message"). By default there's a root logger which can be configured usingbasicConfigand we can also create custom loggers. - Formatters: these objects are in charge of creating the correct representation of the logging event. Most of the time we ant to create a human-readable representation but in some cases we can output a specific format like a json object.

- Filters: We can use filters to avoid printing logging events based on more complicated criteria than logging levels. We can also use filters to modify logging events.

- Handlers: everything comes together in the handlers. A handler defines which formatters and filter a logger is going to use. A handler is also in charge of sending the loging output to the corresponding place, this could be

stdout,emailor almost anythihg else we can think of.

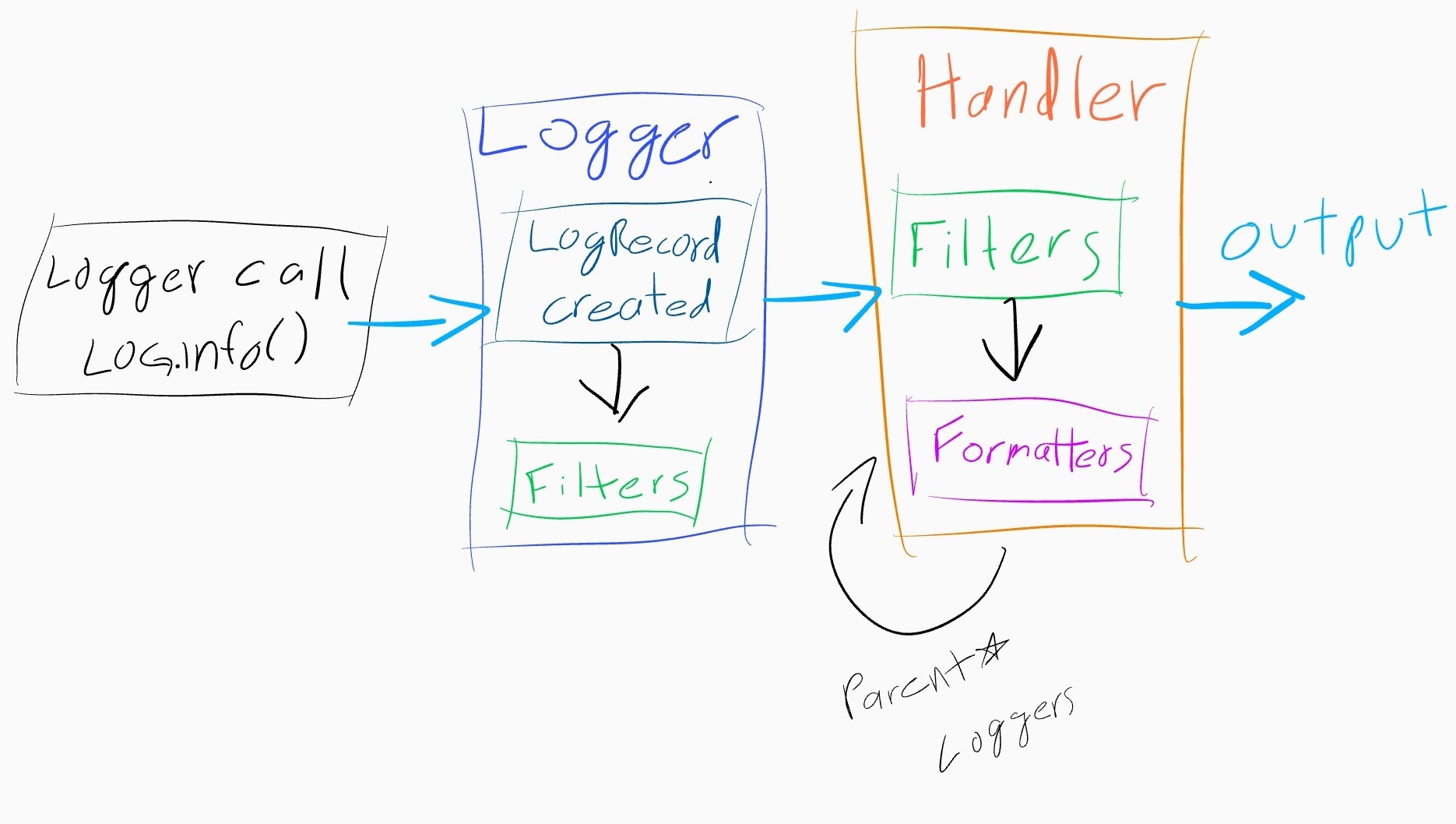

Loggers can have filters and handlers. Handlers can have filters and formatters. We will dive into each one of these parts but it's a good idea to keep in mind how they relate with each other. Here's a visual representation:

Python logger structure

Following Python's philosophies the logging library can be easily used, for example:

import logging

logging.warning("Warning log message.")

And that's it. The example above will print a log message with WARNING level.

If you run the code above you will see this output:

WARNING:root:Warning log message.

The first part of the output (WARNING:root:), comes from

the default logging configuration. The default configuration

will only print WARNING and above levels and will prepend the log level and the name of the logger -- since we haven't created any loggers the root logger is used. More on this later --.

The logger in the example above is the root logger. This is a logger which is the parent of every logger that's created. Meaning, if you configure the root logger then you are basically configuring every logger you create.

What is basicConfig?

To quickly configure any loggers used in your application you can use basicConfig. This method will by default configure the root logger with a StreamHandler to print log messages to stdout and a default formatter (like the one in the example above).

We can configure the logging format using basicConfig. For instance, if we would like to print only the log level, line number, log message and log DEBUG events and up we can do this:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(

format="[%(levelname)s]:%(lineno)s - %(message)s",

level=logging.DEBUG

)

Note:

By usinglogging.basicConfigwe are configuring the root logger

For each log event there is an instance of LogRecord. We can set the format for our log messages using the LogRecord class' attributes and %-style formatting -- %-style formatting is still

used to maintain backwards compatibility --. Since Python 3.2 we can also use $ and {} style to format messages,

but we have to specify the style we're using, by default %-style is used. The style is configured by using the style parameter in basicConfig (logging.basicConfig(style='{')). With the updated configuration we can now see every log level message, for example:

[CRITICAL]:9 - Critical log message.

[ERROR]:10 - Error log message.

[WARNING]:11 - Warning log message.

[INFO]:12 - Info log message.

[DEBUG]:13 - Debug log message.

Best Practice Define a custom log format for easier log parsing.

Note: Use the

LogRecordclass' attributes to configure a custom format.

basicConfig will always be called by the root logger if no handlers are defined, unless the parameter force is set to True (logging.basicConfig(force=True)). By default basicConfig will configure the root logger to output logs to stdout, with the default format of {level}:{logger_name}:{message}.

Custom Loggers

Python's logging library allow us to create custom loggers which will always be children of the root logger.

We can create a new logger by using logging.getLogger("mylogger").

This method only accepts one parameter, the name of the logger. getLogger is a get_or_create method. We can use getLogger with the same name value and we'll be working with the same logger configuration regardless if we're doing this in a different class or module.

The logging library uses dot notation to

create hierarchies of loggers. Meaning, if we create three loggers with the names app, app.models and app.api the parent logger will be app and, app.db and app.api will be the children. Here's a visual representation:

+ app # main logger

|

+ app.api # api logger, child of "app" logger

|

- app.api.routes # routes logger, child of "app" and "app.api" loggers

|

- app.api.models # models logger, sibling of "app.api.routes" logger

|

- app.utils # utils logger, sibling of "app.api" logger

We can get a module's dot notation name from the global variable __name__. Using __name__ to create our custom loggers simplifies configuration and avoids collisions:

# project/api/utils.py

import logging

# Use __name__ to create module level loggers

LOG = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def check_if_true(var):

"""Check if variable is `True`.

:param bool var: Variable to check.

:return bool: True if `var` is truthy.

"""

LOG.info("This logger's name is 'project.api.utils'.")

return bool(var)

Note: If you are defining loggers at the module level (like the example above) is better to stick to global variable naming. Meaning, use

LOGorLOGGERinstead of the lowercase versionlogorlogger.Best Practice

Create loggers with custom names using__name__to avoid collision and for granular configuration.

When using a logger the message's level is checked against the logger's level attribute if it's the same or above then the log message is passed to the logger that's being used and every parent unless one of the logger in the hierarchy sets propagate to False -- by default propagate is set to True --.

How to configure loggers, formatters, filters and handlers

We've talked about using basicConfig to configure a logger but there are other ways to configure loggers. The recommended way of creating a logging configuration is using a dictConfig. The examples in this article will be using dictConfig.

As we've learned before python's logging

library already comes with some useful default values, which makes defining our own formatters, filters and handlers optional. As a matter of fact when using a dictionary to configure logging the only required key is version, and currently the only valid value is 1.

Whenever we use a logger (LOG.debug("Debug log message.")) the first thing that happens is that a LogRecord object is created with our log message and other attributes. This LogRecord instance is then passed to any filters attached to the logger instance we used. If the filter does not reject the LogRecord

instance then the LogRecord is passed to the configured handlers. If any of the configured handlers are enable for the level in the passed LogRecord

then the handlers apply any configured filters to the LogRecord. Finally, if the LogRecord is not rejected by any of the filter the LogRecord is emitted. A more detailed diagram can be seen in python's documentation.

To simplify Python's logging flow we can focus on what happens in a single logger:

Python logging flow simplified

Here's a few important things to note:

- The diagram above is from the point of view of the logger used.

- Filters, handlers and formatters are defined once and can be used multiple times.

- Only the filters and formatters assigned to the parent's handler are applied to the

LogRecord(this is the loop that says "Parent Loggers*")

Every log event created will be processed except in the following cases:

- The logger or the handler configured in the logger are not enabled for the log level used.

- A filter configured in the logger or the handler rejects the log event.

- A child logger has

propagate=Falsecausing events not to be passed to any of the parent loggers. - Your are using a different logger or the logger is not a parent of the one being used.

Formatters

A formatter object transforms a

LogRecord instance into a human readable string or a string that will be consumed by an external service. We can use any LogRecord attribute

or anything sent in the logging call as the extra parameter.

Note: Formatters can only be set to handlers

For example, we can create a formatter to show all the details of where and when a log message happened:

LOGGING_CONFIG = {

"version": 1,

"formatters": {

"detailed": {

"format": "[APP] %(levelname)s %(asctime)s %(module)s "

"%(name)s.%(funcName)s:%(lineno)s: %(message)s"

}

},

"handlers": {

"console": {

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"formatter": "detailed",

"level": "INFO"

}

}

}

When using a dictionary to define a formatter we have to use the "formatters" key. Any key inside the "formatters" object will become a formatter. Every key/value inside the formatter object will be sent as parameters when intializing the formatter instance.

Whenever this formatter is used it will print the level, date and time, module name, function name, line number and any string sent as parameter. We can add other variables not present in LogRecord's attributes by using

the extra attribute:

LOGGING_CONFIG = {

"version": 1,

"formatters": {

"short": {

"format": "[APP] %(levelname)s %(asctime)s %(module)s "

"%(name)s.%(funcName)s:%(lineno)s: "

"[%(session_key)s:%(user_id)s] %(message)s" # add extra data

}

},

#[...]

}

And to send that extra data we can do it like this:

# app.api.UserManager.list_users

LOG.info(

"Listing users",

extra={"session_key": session_key, "user_id": user_id}

)

The output would be:

[APP] INFO 2020-11-07 20:47:00,123 user_manager app.api.user_name.list_users:15 [123abcd:api_usr] Listing users

The downside of referencing variables sent via the extra parameter in a format is that if the variable is not passed the log event is not going to be logged because the string cannot be created.

Best Practice

Make sure to send every additional variable that the configured formatter references if using theextraparameter

Filters

Filters are very interesting. They can be used both at the logger level or at the handler level, they can be used to stop certain log events from being logged and they can also be used to inject additional context into a LogRecord instance which will be, eventually, logged.

The Filter class in Python's logging library filters LogRecords by logger name. The filter will allow any LogRecord coming from the logger name configured in the filter and any of its children.

For instance, if we have these loggers configured:

+ app.models

| |

| - app.models.users

|

+ app.views

|

- app.views.users

|

- app.views.products

And we define the filter config like this:

LOGGING_CONFIG = {

"version": 1,

"filter": {

"views": {

"name": "app.views"

}

},

"handlers": {

"console": {

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"level": "INFO",

"filter": "views"

}

},

"loggers": {

"app": { "handlers": ["console"] }

}

}

We use the "filter" key in a dictionary configuration to define any filters. Each key inside the "filter" object will become a filter we can later reference. Every key and value inside the filter object we create will be sent as parameters when intializing the filter.

The previous configuration will only allow LogRecord coming from the app.views, app.views.users and app.views.products loggers.

When you set a filter to a specific logger the filter will only be used when calling that logger directly and not when a descendant of said logger is used. For example, if we had set the filter in the previous example to the app.view logger instead of the app logger handler. The filter will not reject any LogRecord coming from app.models loggers simply because when using the logger app.models, or any of it's childrens, the filter will not be called.

Let's see how can we create custom filters to prevent LogRecords to be processed based on more complicated conditions and/or to add more data to a LogRecord.

Since Python 3.2 you can use any callable that accepts a record parameter

def custom_filter(record):

"""Filter out records that passes a specific key argument"""

# We can access the log event's argument via record.args

return record.args.get("instrumentation") == "console"

The way to configure these custom classes/callables using a dictionary or a file is by using the special keyword (). Whenever Python's logging config sees () it will create an instance of the class (dot notation has to be used).

Note: When using a dictionary to configure logging you can use the

()keyword to configure custom handlers or filters

Another interesting thing about filters is that they see virtually every LogRecord that might be logged. This makes filters a great place to further customize LogRecords. This is called "adding context".

Custom filter example

The following custom filter will apply a mask to every password passed to a LogRecord if the pwd or password key is used.

# module: app.logging.filters

def pwd_mask_filter(record)

"""A factory function that will return a filter callable to use."""

def filter(record):

# a Logger cord instance holds all it's arguments in record.args

def mask_pwd(record):

return '*' * 20

if record.args.has_key("pwd"):

record.args["pwd"] = mask_pwd()

elif record.args.has_key("password"):

record.args["pwd"] = mask_pwd()

return filter

LOGGING_CONFIG = {

"version": 1,

"formatters": {

"detailed": {

"format": "[APP] %(levelname)s %(asctime)s %(module)s "

"%(name)s.%(funcName)s:%(lineno)s: %(message)s"

}

},

"filters": {

"mask_pwd": {

"()": "app.logging.filters.mask_pwd"

}

},

"handlers": {

"console": {

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"formatter": "detailed",

"level": "INFO",

"filters: ["mask_pwd"]

}

}

}

When using () in a dictionary configuration the referenced module will be imported and instantiated. In this case the factory function mask_pwd will be called and the actual function that handles filtering will be returned.

Handlers

Handlers are objects that implement how formatters and filters are used. if we remember the flow diagram we can see that whenever we use a logger the handlers of all the parent loggers are going to be called recursivley. This is where the entire picture comes together and we can take a look at a complete loggin configuration using everything else we've talked about.

Python offers a list of very useful handlers. Handler classes have a very simple API and in most cases we will only use these classes to add a formatter, zero or more filters and setting the logging level.

Note:

Only one formatter can be set to a handler.

For instance, the following configuration makes sure that every log is printed to the standard output, uses a filter to select a different handler depending if the application is running in debug mode or not and it uses a different format for each different environment (based on the debug flag).

Full logging configuration example

LOGGING = {

"version": 1,

"disable_existing_loggers": False,

"formatters": {

"long": {

"format": "[APP] {levelname} {asctime} {module} "

"{name}.{funcName}:{lineno:d}: {message}",

"style": "{"

},

"short": {

"format": "[APP] {levelname} [{asctime}] {message}",

"style": "{"

}

},

"filters": {

"debug_true": {

"()": "filters.require_debug_true_filter"

},

"debug_false": {

"()": "filters.require_debug_false_filter"

}

},

"handlers": {

"console": {

"level": "INFO",

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"formatter": "short",

"filters": ["debug_false"]

},

"console_debug": {

"level": "DEBUG",

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"formatter": "long",

"filters": ["debug_true"]

}

},

"loggers": {

"external_library": {

"handlers": ["console"],

"level": "INFO"

},

"app": {

"handlers": ["console", "console_debug"],

"level": "DEBUG"

}

}

}

When using a dictionary configuration disable_existing_loggers is set to True by default.

What this does is that it will grab all the loggers created before the configuration is applied and disable them so they cannot process any log events. This is specially important when creating loggers at the module level.

Say we have a app.models.client module in which we create a logger like this:

# app.models.client

import logging

LOG = logging.getLogger(__name__)

class Client:

# ...

And then in our application's entry point we import our models and configure our logging:

# app.__main__

import logging

from app.settings.logging import LOGGING_CONFIG # A dictionary

from app.models import Client

logging.config.dictConfig(LOGGING_CONFIG)

In this case the logger created in app.models.client will not work unless disable_existing_loggers. Because when we import the Client class from app.models we are initializing the logger used in app.models.client. Then, after the logger is already initialized we apply our configuration, making any existing loggers disabled.

When definig a handler using a dictionary, any key that is not class, level, formatter or filters will be passed as a parameter to the handler's class specified for instantiation.

Filters cannot be used when using a file to configure logging. One more reason why is better to use a dictionary for configuration.

Things to lookout for when configuring your loggers

- Filters can be set both to Loggers and Handlers. If a filter is set at the logger level it will only be used when that specific logger is used and not when any of its descendants are used.

- File config is still support purely for backwards compatibility. Avoid using file config.

()can be used in config dictionaries to specify a custom class/callable to use as formatter, filter or handler. It's assumed a factory is referenced when using()to allow for complete initialization control.- Go over the list of cases when a log event is not processed if you don't see what you expect in your logs.

- Make sure to set

disable_existing_loggerstoFalsewhen using dict config and creating loggers at the module level.

Recommendations for better logging

- Take some time to plan how your logs should look like and where are they going to be stored.

- Make sure your logs are easily parsable both visually and programmatically, like using

grep. - Most of the time you don't need to set a filter at the logger level.

- Filters can be used to add extra context to log events. Make sure any custom filters are fast. In case your filters do external calls consider using a queue handler

- Log more than errors. Make sure whenever you see an error in the logs you can trace back the state of the data in the logs as well.

- If you are developing a library, always set a

NullHandlerhandler and let the user define the logging configuration. - Use the handlers already offered by Python's logging library unless is a very special case.

Most of the time you can hand off the logs and then process them with a more specialized tool.

For example, send logs to

syslogusingsyslogHandlerhandler and then usersyslogto maintain your logs. - Create a new logger using the module's name to avoid collisions,

logging.getLogger(__name__)

Note: If you want to use the test the configuration above or just play around with different configs, checkout the complementary repo to this article

Special thanks to Žan Anderle for proof reading.

If you liked this content make sure to follow me on twitter @rmcomplexity