South Korean pop music, known as K-Pop, is one of the most popular music genres in the world. With catchy pop hits and intricate choreography, K-Pop groups such as BTS and Black Pink have attracted deeply dedicated fans from around the world.

Individual K-Pop group members are referred to as “idols.” Idols are known for their carefully developed public personalities, which are often strictly controlled by their music labels, because fans’ emotional attachments to individual idols are extremely profitable. Within the past few years, the industry has pioneered a new way to monetize fans’ emotional needs by creating dedicated mobile apps, such as Bubble and Universe, that simulate private messaging between idols and fans.

We conducted a series of interviews and qualitative usability testing with adult K-Pop fans in Seoul, South Korea, to better understand their perspectives on the new service.

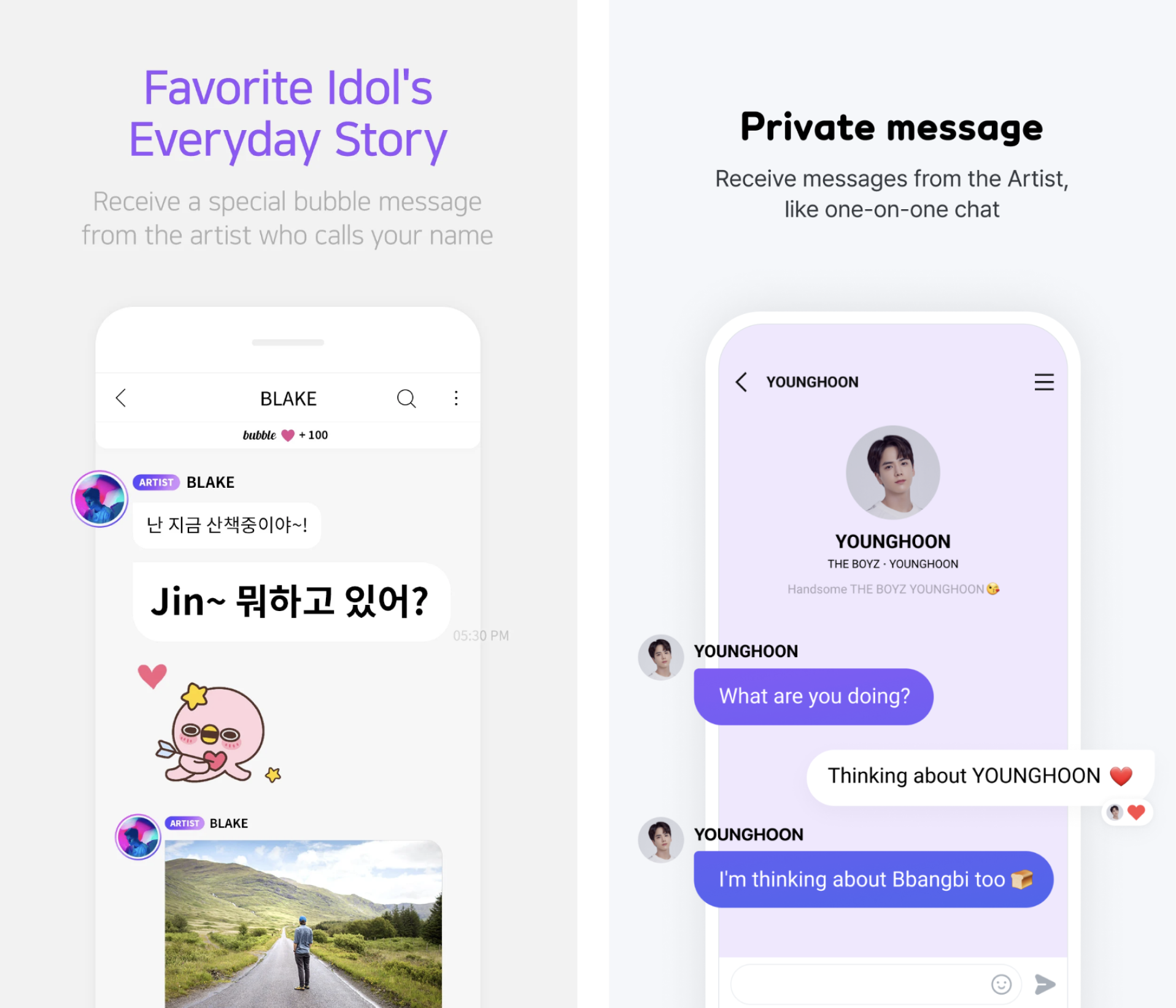

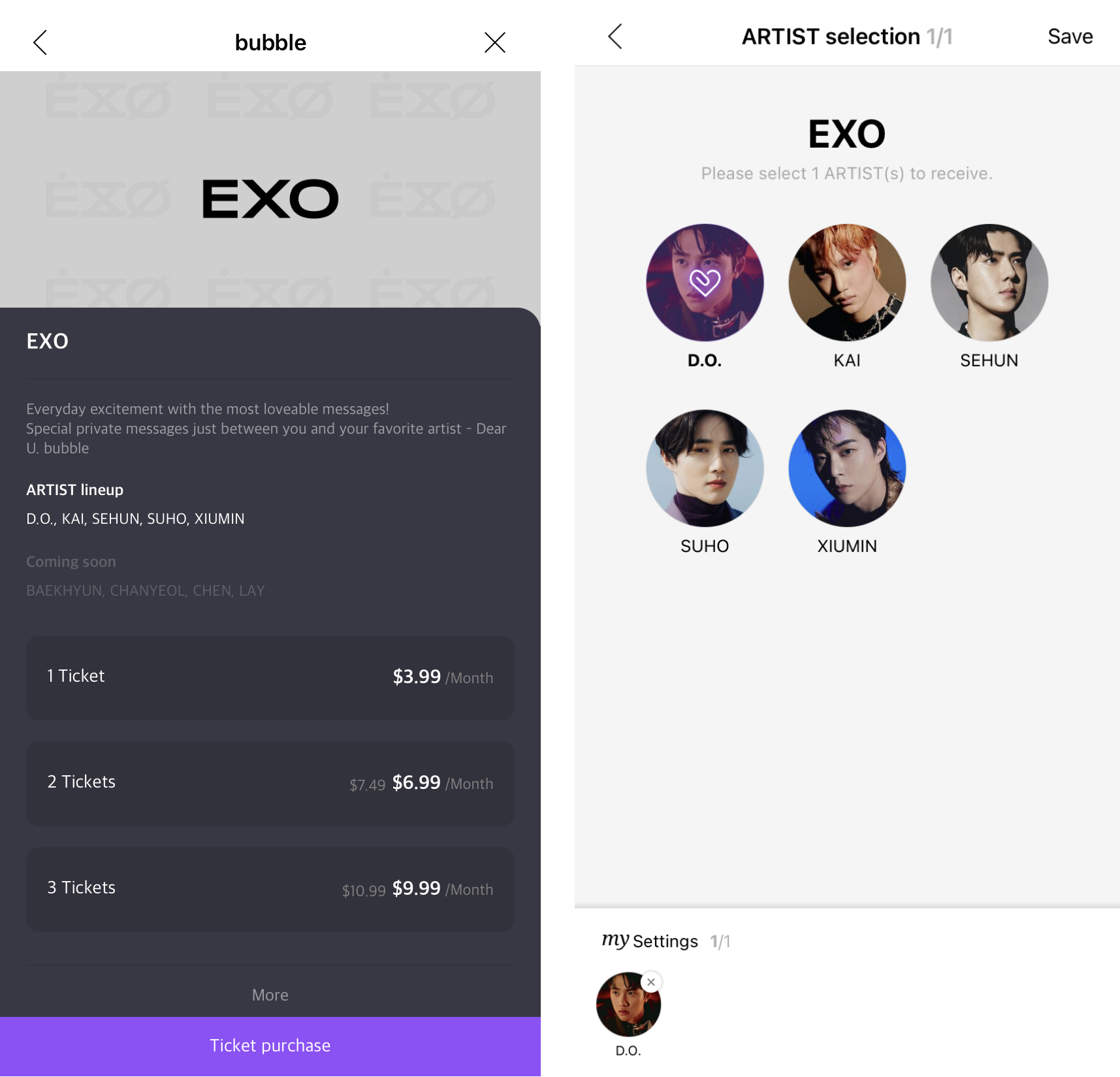

Mobile apps such as Bubble and Universe offer an online chat service where fans can pay to communicate with idols in a one-on-one chat room.

Fans feel as though they are receiving a private message, written just for them, from their favorite idol. However, in reality, idols do not reply individually to each fan message. The goal is to make fans feel as if they have direct access to their favorite idols and thus strengthen their emotional attachment to these stars and increase profits.

The first instance of simulated private messaging appeared in the Bubble app, owned by the K-Pop label SM Entertainment. To chat with each idol, fans need to purchase a monthly subscription plan on the application’s STORE page — a blunt commoditization of idols’ time and attention.

Developing a “Personal” Connection

After users pay to chat with a specific idol, a new private chat room is created and the fans start receiving the idol’s messages. Some artists text several times a day, while others just once a month. Idols typically send updates about what they are currently doing or thinking — for example, what they ate for lunch, selfies of their day-to-day life, and song recommendations. This content may seem mundane, but it helps fans feel as if they know the idol personally. Moreover, each idol seems to have a unique texting style — for example, some send longer text messages and others heavily use emojis. This consistency in the idol’s “personality” helps to persuade fans that it’s truly that person behind the screen.

Some messages go beyond a simple text. Idols occasionally send voice messages to say good morning or goodnight, or short audio clips of them humming an unreleased song. Moreover, some idols even share private stories that they wouldn’t post on social media such as recounts of their psychological struggles. These kinds of messages make fans feel as though they’re seeing the “real” person rather than a polished celebrity, and further reinforce the emotional connection with the idols.

The Illusion of Private Chatting

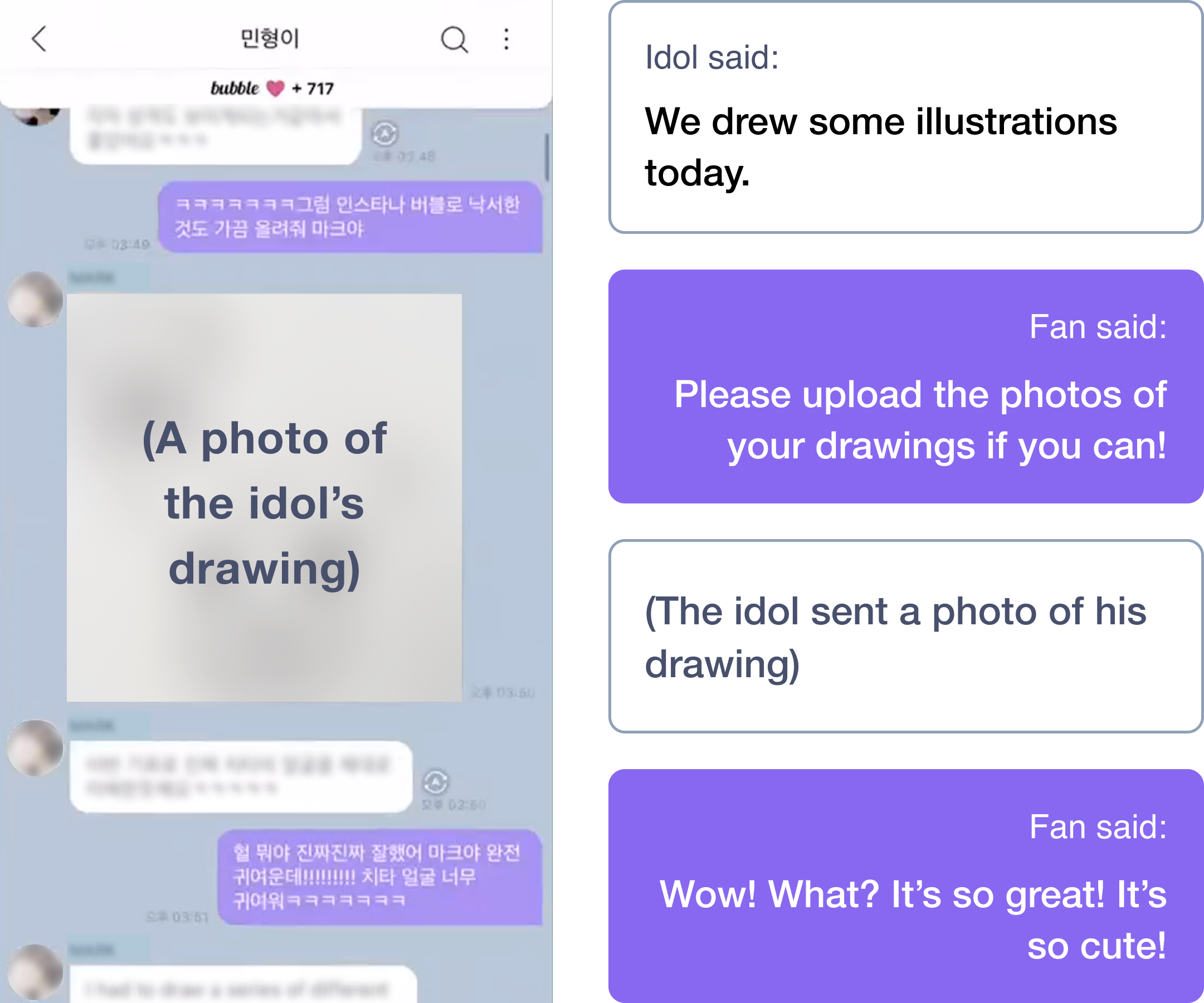

In the private chat window, fans can send a limited number of replies to each of the idol's messages. Each message needs to be within a prescribed length, which grows as the fan's subscription days grow.

While these apps create the illusion of private messaging to fans, it is an open secret that they aren’t really a one-on-one chat with an idol. Although we do not know what the idol's side of UI exactly looks like, some K-Pop stars shared in online posts that idols see a group chat containing all the fans’ replies and where they can drop messages for everyone at once.

Since an idol will receive thousands of messages from fans, it’s impossible to respond to each in a personalized way. As a result, an individual fan’s view of the conversation often appears out of sync. For example, a fan might text, “I’m excited about your new album!” and the artist replies, “No, I haven’t eaten anything today.”

These moments of disconnect risk shattering the illusion that the apps work to create. Yet fans seem to ignore such mismatches (as well as others discussed later) and highly value the rare times when the idol’s response matches the fan’s message.

One K-pop fan who used Bubble told us:

“I often ask my idol ‘What did you have for lunch?’ on Bubble. Typically, his replies are totally unrelated to my question. But once, he replied ‘I had pasta.’ I guess many other fans asked about it, too, but who cares? That moment, I just felt so happy thinking that he responded to me.”

Participants told us that a single moment like this one helped them forget all other mismatching conversations.

Practically, this communication model is not much different from one-sided social-media posts, where thousands of fans leave comments on a celebrity’s page, hoping they reach the artist. The odds that the celebrity will see the post and individually respond to the fan are very low. On the other hand, K-Pop private messaging services wrap that same model in the illusion that the communication is personal and private. They offer one-to-many communication in the guise of one-to-one communication.

This might sound like a scam, but fans are fully aware of the illusion. “Fans are paying for the private-messaging experience itself,” said one participant in our study. To enjoy the experience, fans consciously — or unconsciously — choose to believe in the illusion. Moreover, participants told us that they are now so accustomed to this special experience that they can’t be satisfied with the one-sided social-media-based communication of the past anymore.

Visual Design: Replicating Private Chat

One way in which K-Pop private messaging apps support this illusion is visual design — the interaction between the idol and the fan intentionally looks like a one-on-one chat. Fans cannot see what other fans sent to the idol, so it’s easy for them to ignore the fact that the idol receives replies from many other fans.

Moreover, as observed by many fans, the visual design and layout used by Bubble are strikingly similar to Korea’s most popular messenger app, Kakao Talk. Fans said that this similarity to their day-to-day messenger strengthens the feeling of a private, genuine chat experience.

When a fan sends a message in Bubble, the number 1 is shown in a small gray font next to the text bubble. The number disappears when the receiver checks the message. Although it’s likely that the idol doesn’t read each message carefully, the small visual indicator makes fans believe that their message did reach the artist. This is another way Bubble mimics Kakao Talk, which also uses the number 1 to indicate that the message was not read yet.

Other than this visual clue, there is no way fans can find out whether the artist read their message or whether it was really the idol who read the message. Regardless, fans love this small detail as it makes their efforts feel meaningful. One participant told us:

“Whenever I see the number 1 disappear, I can sense that there is really a human being behind the screen reading my messages. Visually seeing that my messages did reach the idol makes me think that my payment is worth it.”

This visual detail sets private messaging apart from traditional social-media communication, where fans would never know whether their comments or messages have reached the idol.

Personalization: Calling the Fan by Name

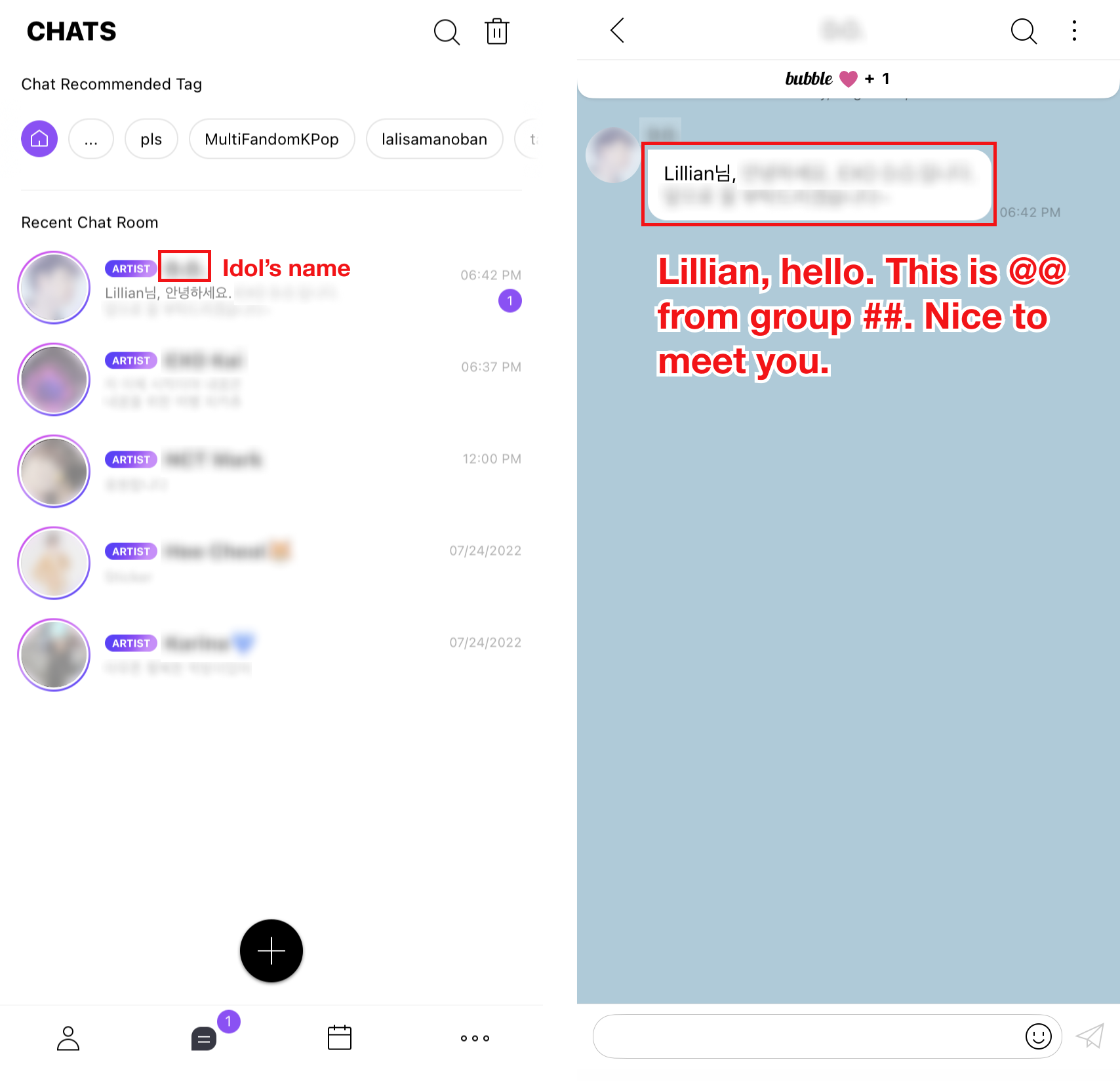

These apps further enhance the illusion of private chat by heavily utilizing username variables to make each fan feel as if they are spoken to personally.

Idols often send messages that contain the fan’s exact profile name, which can be quite surprising to a new user. In reality, idols are using a function inside of their message app that replaces the string ‘%username’ to each fan’s set name in the app. (Remember that the same message will appear in many different fans’ private chats.)

Idol view: Good night, @username!

👉 Fan 1 view: Good night, Lillian Yang!

👉 Fan 2 view: Good night, John Smith!

While many of our participants appreciated these personalization tactics, K-Pop apps should be cautious with automated attempts to simulate intimacy. In our research, we found that these methods sometimes backfired and made the experience feel disingenuous.

In particular, some of the messages containing fans’ names might look grammatically incorrect in Korean. This is because in the Korean language a different postposition must be used based on how the name ends.

Fans say these moments break the illusion and make them aware that the chat is not genuinely private and personalized. Yet, fans easily ignore these uncanny moments (like they forgive mismatches between their messages and the idol’s replies), because they put value into the private-messaging experience as a whole and not in the small details. There seems to be a willful choice among fans to stay in the illusion of the one-on-one chat, even when presented with obvious contradictory evidence.

Gamification: Presenting the Subscription as a “Relationship”

Some apps use gamification to immerse users into the one-on-one chat experience. In Bubble, as soon as a fan starts subscribing to an idol, a counter with a heart icon appears in the chatroom. The count increases each day that the user remains subscribed but stops when the fan cancels the subscription.

This tactic mimics a real-world relationship practice in South Korea, where couples count the days from when they became exclusive (for example, a couple might celebrate 50 or 100 days of dating). This mapping with the real world strengthens the fan’s bond with the idol and increases the illusion of a personal relationship.

To reward users who maintained the subscription long enough, a flashy popup appears every 100, 200, and 300 days to celebrate each “anniversary” of the fan and the idol’s “relationship.”

In addition, the longer a fan has been subscribed to an idol, the longer their messages are allowed to get. In essence, the day count works as a quantification of how much the fan is dedicated to their idol.

One participant told us:

“The heart counter definitely works, especially when I’m indecisive about canceling the subscription or not. I get to think twice because I just don’t want to lose the days count I developed for 2 years.”

This is a great example of sunk-cost fallacy — the psychological phenomenon in which people are reluctant to abandon a course of action because they have invested heavily in it. In this case, fans are encouraged to consecutively maintain the subscription to avoid losing their emotional and financial investment.

Deceptive Pattern: Guilt-Tripping Fans

If fans do cancel a subscription, there is yet another tactic used to change their minds. Once unsubscribed, the chatroom shows a broken heart emoji with the message One day we will meet again — as if the idol is talking to the fan. This is a deceptive pattern intended to make the fan feel guilty for ending the “relationship.”

While the ethics of this design tactic is questionable, it does seem to be effective at persuading users to reconsider. One participant who unsubscribed from Bubble to save money said:

“Reading this breakup message is painful. I feel sorry for my idol and want to repair that broken heart. I’ll resubscribe as soon as I get more money.”

These layers of emotional design enhance the illusion of a real relationship and act as successful buffers keeping fans from unsubscribing.

Conclusion

Private messaging offers a new way for fans to interact with celebrities. Many K-Pop fans are already mature consumers of this superficial yet intimate-feeling interaction. They also seem to be aware of the blunt business model and are surprisingly open to the psychological and emotional strategies used by these apps. They are becoming a part of fandom culture and people appreciate their unique experience compared to other social platforms.

It's likely that AI tools will improve the sophistication of these apps, reducing the awkward, jarring moments that chip away at the illusion. However, the core value of these services is the human connection (real or illusional).

By exploring fans’ emotional boundaries, the private-messaging experience is generating substantial revenue. According to Korean capital-market company IBK Security, the Bubble app made a profit of US $13 million in 2021 with 1.2 million users. 90% of the users were consecutive subscribers and 72% were from outside of Korea.

This trend will soon go beyond K-Pop. Recently, Bubble launched a subsidiary app, Bubble for SPORTS, providing messaging access to several sports stars. Private messaging apps have also announced plans to expand the experience to global celebrities, YouTube creators, and even virtual characters. This new way of one-to-one digital communication might become a new norm in the near future.