Facebook has long said that it doesn’t use location data to make friend suggestions, but that doesn’t mean it hasn’t thought about using it.

In 2014, Facebook filed a patent application for a technique that employs smartphone data to figure out if two people might know each other. The author, an engineering manager at Facebook named Ben Chen, wrote that it was not merely possible to detect that two smartphones were in the same place at the same time, but that by comparing the accelerometer and gyroscope readings of each phone, the data could identify when people were facing each other or walking together. That way, Facebook could suggest you friend the person you were talking to at a bar last night, and not all the other people there that you chose not to talk to.

Facebook says it hasn’t put this technique into practice.

“We’re not currently using location [for People You May Know],” said a Facebook spokesperson. Facebook has previously told us that it only used location for friend recommendations one time during a brief test in 2015. But several of its patents show it thinking about using location, also recommending users friend each other, for example, if they “check into the social network from the same location at around the same time.”

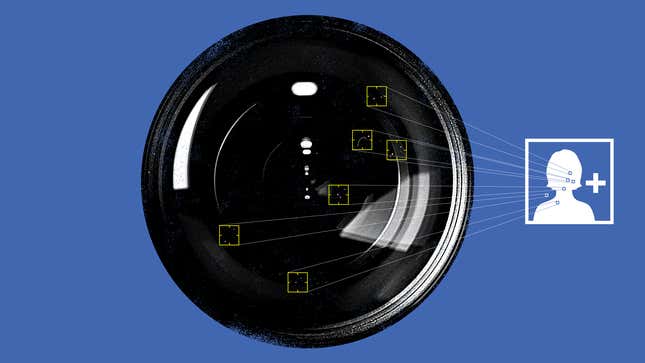

In the course of our year-long investigation into how the social network makes its uncannily accurate friend recommendations to users, Facebook has told us many things it doesn’t do, to ease fears about Facebook’s ability to spy on its users: It doesn’t use proxies for location, such as wi-fi networks or IP addresses. It doesn’t use profile views or face recognition or who you text with on WhatsApp. Most of Facebook’s uncanny guesswork is the result of a healthy percentage of users simply handing over their address books.

But that doesn’t mean Facebook hasn’t thought about employing users’ metadata more strategically to make connections between them. Patents filed by Facebook that mention People You May Know show some ingenious methods that Facebook has devised for figuring out that seeming strangers on the network might know each other. One filed in 2015 describes a technique that would connect two people through the camera metadata associated with the photos they uploaded. It might assume two people knew each other if the images they uploaded looked like they were titled in the same series of photos—IMG_4605739.jpg and IMG_4605742, for example—or if lens scratches or dust were detectable in the same spots on the photos, revealing the photos were taken by the same camera.

It would result in all the people you’ve sent photos to, who then uploaded them to Facebook, showing up in one another’s “People You May Know.” It’d be a great way to meet the other people who hired your wedding photographer.

“We’re also not analyzing images taken by the same camera to make recommendations in People You May Know,” said a Facebook spokesperson when asked about the patent. “We’ve often sought patents for technology we never implement, and patents should not be taken as an indication of future plans.”

The technological analysis in some of the patents is pretty astounding, but it could well be wishful thinking on Facebook’s part.

Vera Ranieri, an attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation who focuses on intellectual property, hasn’t reviewed these specific patents but said generally that the U.S. Patent Office doesn’t ensure that a technology actually works before granting a patent.

“A lot of patents are filed at the idea stage rather than the actuality stage,” said Ranieri by phone. “A tech company that files a patent has, hopefully, at least thought about how to do it. You’d hope they could implement it if asked, but it doesn’t mean they have done so before.”

Since being born into the world in 2004, Facebook has filed for thousands of technology patents in order to lock down its intellectual property and, like many in the field, stifle competition. In a search of those patents, we found a dozen, filed from 2010 to 2016, that were directly relevant to People You May Know, or PYMK as it’s called internally. They include techniques that Facebook could use one day to make friend suggestions—or techniques it could sue someone else for using.

Taken in their breadth, they speak to the many sources of information Facebook could tap to learn more about us and our real-world social networks, thanks in large part to the sophisticated surveillance tools built by default into our smartphones, such as accelerometers, gyrometers, microphones, cameras, and endless, sprawling contact books.

The Facebook employees and contractors who authored the patents repeatedly explain why People You May Know is so crucial to the network: People with more friends use the network more and look at more ads. Without People You May Know, the $500 billion behemoth that is Facebook would be making less money. That may be why users aren’t allowed to opt out of the feature, even when it carries risks for them.

“For people with low friends counts—usually new to Facebook—we’ve heard that the suggestions we provide help them feel more engaged, and we’re going to continue to try to make these suggestions as relevant as possible,” said the Facebook spokesperson by email. “Concerning how People You May Know works; we prioritize suggestions based on mutual friends because having friends in common is a good signal that you may want to be friends with someone on Facebook.”

Facebook’s earliest People You May Know patent was filed in 2010, two years after Facebook launched the feature. In it, employees from Facebook explain why friend suggestions are important:

“Social networking systems value user connections because better connected users tend to use the social networking system more, thus increasing user engagement and providing a better user experience.”

In a patent filed two years later, employees on Facebook’s growth team explain why increased user engagement is so important. It leads to “a corresponding increase in, for example, advertising opportunities.”

In other words, People You May Know is crucial to Facebook’s bottom line. Thus, Facebook’s first PYMK patent was on the process of privileging friend recommendations for people who don’t have very many friends. Another filing patents the act of aggressively displaying “People You May Know” to people who don’t use Facebook very often.

Its second patent was for something Facebook doesn’t currently let you do: sort its friend suggestions to you and rank them by hometown or number of mutual friends or their interests. (If you’re interested in actually being able to do that, try our PYMK Inspector, which will let you sort your friend suggestions by mutual friends.)

One of its patents is for figuring out who your family members are and suggesting them as friends. It says it could figure this out based on “external feeds, third-party databases, etc.” However, when Facebook suggested I friend a relative I didn’t know I had, Facebook told me it doesn’t use information from third parties or data brokers for People You May Know.

While Facebook says it often seeks patents for technology it never implements, one thing Facebook is doing—and that it has filed multiple patents on since 2012 because it works so well—is building shadow profiles to connect users. Facebook collects all the contact information it can find for you from other users’ address books and then associates it with your account—though not in a place you can see or delete. It then uses that information to connect you with other users who have those contact deets for you. In patent speak, this is “Associating received contact information with user profiles stored by a social networking system.”

Here’s how Facebook describes the process of figuring out everyone you’ve ever met.

[U]ser profiles may include incomplete or outdated information, limiting the social networking system’s ability to identify other social networking system users for connecting to an importing user. To more accurately identify users, the social networking system stores contact entries received from an importing user and associates a stored contact entry with a user profile including information matching information in the contact entry. Subsequently received contact entries are compared to user profiles and stored contact entries associated with the user profile to identify matching information. If information in a user profile or in a stored contact entry associated with the user profile matches a received contact entry, a user associated with the user profile is identified for establishing a connection. Associating received contact entries with user profiles supplements user profiles with received content information, allowing identification of more potential connections to users and increasing user interaction with the social networking system.

And, of course, more user interaction means more opportunities to look at ads.

As Facebook continues to grow, through app acquisitions and claiming new demographics and countries as users, it will do its best to connect those new users to its existing billion-plus members. We can’t know when or if Facebook will ever actually scan digital photos for dust or tap into our phones’ gyrometers to more fully map the relationships between all the people in the world, but we now know, thanks to the U.S. Patent Office, that Facebook at least thinks these things are possible.

With that kind of thinking happening internally at Facebook, it’s hard not to start thinking of it more as a spy service than a social network. If these techniques were put into practice, it would be an incredibly invasive level of tracking in service of suggesting you connect with people that you may not actually want Facebook to know that you know.

Contact the Special Projects Desk

This post was produced by the Special Projects Desk of Gizmodo Media. Reach our team by phone, text, Signal, or WhatsApp at (917) 999-6143, email us at tips@gizmodomedia.com, or contact us securely using SecureDrop.