Criminals in 2017 managed to get an advanced backdoor preinstalled on Android devices before they left the factories of manufacturers, Google researchers confirmed on Thursday.

Triada first came to light in 2016 in articles published by Kaspersky here and here, the first of which said the malware was "one of the most advanced mobile Trojans" the security firm's analysts had ever encountered. Once installed, Triada's chief purpose was to install apps that could be used to send spam and display ads. It employed an impressive kit of tools, including rooting exploits that bypassed security protections built into Android and the means to modify the Android OS' all-powerful Zygote process. That meant the malware could directly tamper with every installed app. Triada also connected to no fewer than 17 command and control servers.

In July 2017, security firm Dr. Web reported that its researchers had found Triada built into the firmware of several Android devices, including the Leagoo M5 Plus, Leagoo M8, Nomu S10, and Nomu S20. The attackers used the backdoor to surreptitiously download and install modules. Because the backdoor was embedded into one of the OS libraries and located in the system section, it couldn't be deleted using standard methods, the report said.

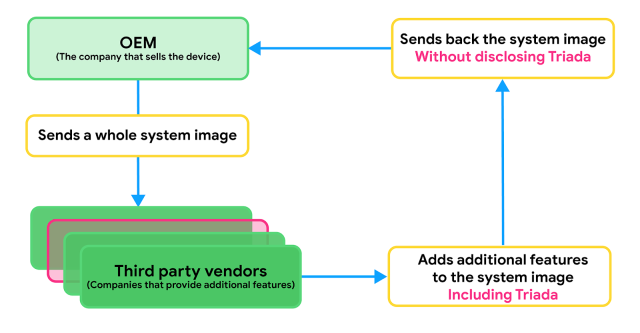

On Thursday, Google confirmed the Dr. Web report, although it stopped short of naming the manufacturers. Thursday's report also said the supply chain attack was pulled off by one or more partners the manufacturers used in preparing the final firmware image used in the affected devices. Lukasz Siewierski, a member of Google's Android Security & Privacy Team, wrote:

Triada infects device system images through a third party during the production process. Sometimes OEMs want to include features that aren't part of the Android Open Source Project, such as face unlock. The OEM might partner with a third party that can develop the desired feature and send the whole system image to that vendor for development.

Based on analysis, we believe that a vendor using the name Yehuo or Blazefire infected the returned system image with Triada.

Thursday's post also expanded on previous analysis of the features that made Triada so sophisticated. For one, it used XOR encoding and ZIP files to encrypt communications. And for another, it injected code into the system user interface app that allowed ads to be displayed. The backdoor also injected code that allowed it to use the Google Play app to download and install apps of the attackers' choice.

"The apps were downloaded from the C&C server, and the communication with the C&C was encrypted using the same custom encryption routine using double XOR and zip," Siewierski wrote. "The downloaded and installed apps used the package names of unpopular apps available on Google Play. They didn't have any relation to the apps on Google Play apart from the same package name."

Mike Cramp, senior security researcher at mobile security provider Zimperium, agreed with the assessments that Triada's capabilities were advanced.

"From the looks of it, Triada seems to be a relatively advanced piece of malware including C&C capabilities, and in the beginning, shell execution capabilities," Cramp wrote in an email. "We do see a lot of adware, but Triada is different in that it uses C&C and other techniques that we would usually see more in the malicious malware side of things. Yes, this is all used to ultimately deliver ads, but the way they go about it is more sophisticated than most adware campaigns. It pretty much is an 'adware on steroids.'"

Siewierski said Triada developers resorted to the supply-chain attack after Google implemented measures that successfully beat back the backdoor. One was mitigations that prevented its rooting mechanisms from working. A second measure was improvements in Google Play Protect that allowed the company to remotely disinfect compromised phones.

The Triada version that came preinstalled sometime in 2017 didn't contain the rooting capabilities. The new version was "inconspicuously included in the system image as third-party code for additional features requested by the OEMs." Google has since worked with the manufacturers to ensure the malicious app was removed from the firmware image.

Not the first time

Last year, Google implemented a program that requires manufacturers to submit new or updated build images to a build test suite.

"One of these security tests scans for pre-installed PHAs [potentially harmful applications] included in the system image," Google officials wrote in their Android Security & Privacy 2018 Year In Review report. "If we find a PHA on the build, we work with the OEM partner to remediate and remove the PHA from the build before it can be offered to users."

Still, Thursday's report acknowledges that, as Google tightens security in one area, attackers are sure to adapt by exploiting new weaknesses.

"The Triada case is a good example of how Android malware authors are becoming more adept," Siewierski wrote. "This case also shows that it's harder to infect Android devices, especially if the malware author requires privilege elevation."

reader comments

116