Building Broadacre: Jennifer Gray in Conversation with David Romero

Jennifer Gray | Jan 12, 2022

Jennifer Gray speaks with designer David Romero about his research and process when creating a virtual model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s ambitious Broadacre City concept.

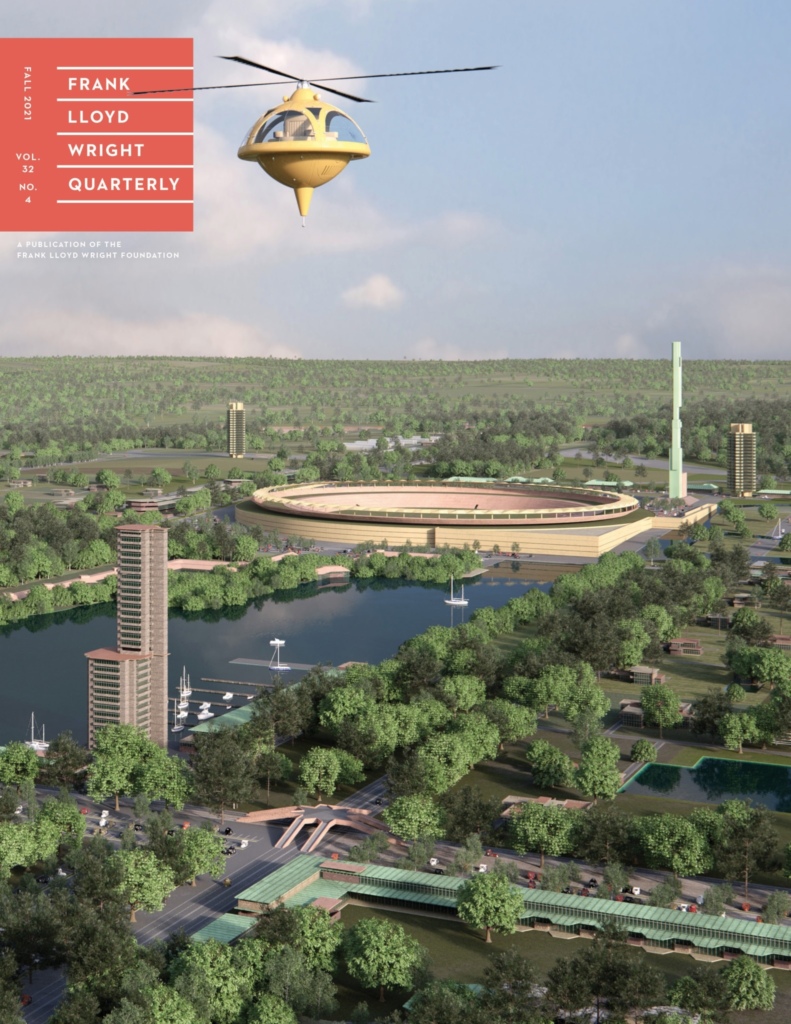

In 1935, Frank Lloyd Wright and his apprentices constructed a model of Broadacre City, an ambitious vision for reshaping the entire built environment along decentralized lines. The idea of Broadacre, also expressed through multiple books and drawings, was as much a theory about society as it was an architectural plan, which complicates any attempt to model or visualize it. Today, designer David Romero has taken on this challenge and created a virtual model of Broadacre using advanced computer modeling techniques. Jennifer Gray speaks with him about his research and design process.

Render by David Romero

Jennifer Gray:

How complex was it to virtually recreate the physical model of Broadacre City that Wright developed in 1935?

David Romero:

It was not complex in the sense that it was spatially difficult to model. Gordon Strong’s spiral building, for example, was much more difficult. But it was a challenge because the Broadacre model includes within it more than a hundred buildings, each of which had to be modeled with a higher level of detail than the original physical model. If to this we add the landscape, the roads, all the details of the urbanization, we are talking about a daunting task. Modeling Broadacre took me over eight months. This is the model that has taken me the longest to make.

JG:

You mentioned that you increased the level of detail in your virtual model with respect to the original model. What sources did you use to do that?

DR:

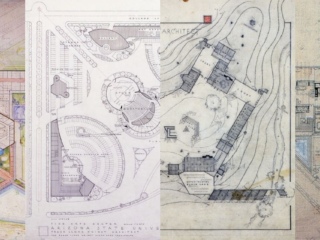

Well, the first source, apart from the physical model, are the drawings that Wright made to illustrate his book The Living City. But when I started working, I realized that those drawings are completely different from the physical model. Which is okay, they still provide a wealth of details about the ideas Wright wanted to illustrate. And his ideas about Broadacre were not thought to be built in concrete ways, they’re theoretical ideas. Which is fine, but for me this was complicated because usually when I recreate Wright’s unbuilt works, it’s a building intended to be constructed in a specific place, with specific materials, and that wasn’t the case here. But in the end, that gave me some freedom too. In addition, many of the buildings that Wright introduced in his 1935 model are recycled from previous projects that he never built but for which we do have detailed drawings, such as the San Marcos Water Gardens, St. Mark’s Tower Project, or the Prefabricated Steel Sheet Agricultural Units, among others. So, I also studied those buildings and I make a mix with all that.

Drawing for ‘The Living City’, Frank Lloyd Wright. Image courtesy of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

JG:

What are the technical challenges involved in making such a large virtual model?

DR:

To understand the technical complexity involved in creating a virtual model of Broadacre, here are some statistics. The virtual model contains more than one hundred buildings, of which all the exterior facades have been modeled, including their doors and windows. There also are one hundred ships, two hundred “aerotors,” 5,800 cars, and more than 250,000 trees in the virtual model. Each of these objects is a highly detailed and complex element with hundreds of thousands of three-dimensional polygons, so we are talking about a model with billions of polygons. To make this possible without depleting the memory of the most powerful computer, a system called proxy is used that imports a geometry from an external file only at the time of rendering, thus avoiding the use of huge amounts of memory that would not otherwise be possible to perform. Finally, there is the task of distributing all these objects in a coherent way throughout the model, a process that varies from the purely manual, in the case of buildings, to a semi-random distribution with the help of specialized software. For example, there are only four different trees, but they are completely scattered throughout the model, just rotating, changing the scale, things like that. Little tricks like that so they all look different. In the end, that’s something the computer can handle.

Render by David Romero

JG:

In recreating Broadacre, you also had to model industrial designs, namely Wright’s designs for automobiles and helicopters that he called “aerotors.” What difficulties were involved in modeling these transportation vehicles?

DR:

Leaving aside that these types of vehicles have complex surfaces that require specific modeling techniques, the main challenge was adding details to designs that have never been manufactured. When I model architecture, I can see other works by Wright that have been built, but in this case, what reference to take? When Wright designed these, he thought it would be something futuristic. So, do I want to show something futuristic, but futuristic from our future, or from the future of the past? At the end, I decided to make something retro-futuristic, something from the future but imagined in the 1930s. So, I studied cars of the time as well as prototypes. A reference that seemed especially relevant to me was the Dymaxion Car by Buckminster Fuller, a design that has points in common with Wright’s ideas.

Drawing of Road Machines by Frank Lloyd Wright | Render of Road Machines by David Romero

JG:

What kinds of artistic liberties or judgement calls did you have to make when modeling Broadacre? And why, what information was missing?

DR:

A big challenge was to fill the gaps that are not in the physical model. For example, I had to think what to do in the landscape surrounding the model. Where is Broadacre located? Maybe that looks close to a landscape in Kansas? Which textures to use? So, we finally chose some ground textures that look like the Midwest.

JG:

Right, Broadacre is really a thought experiment, not intended to be built. Wright famously says of Broadacre that it is “nowhere or everywhere.” So, trying to situate it in a specific topography or geography gets complicated.

DR:

Yes, it is difficult to decide which point of view we can use. It can be everywhere. His ideas were not specific to a place. From the beginning of this project, a tricky question has always been what level of abstraction was appropriate. We finally decided to make a realistic model, even if that meant making decisions about the location, what kind of vegetation to use, or what the terrain would look like. Usually when I work with Wright models, I don’t want to speculate. I don’t want to do something like my version of Frank Lloyd Wright. I want to work more like a documentary filmmaker. But here, there is nothing like Broadacre. In this sense, Broadacre is a very interpretable project since the place where it is located was invented by Wright, and I therefore had more freedom than in other works. It is interesting to wonder what images or videos Wright would have produced had computers existed in his time. Like everything Wright did, he surely would have impressed his exuberant personality through the use of this tool.

Render by David Romero.

The full scope of David Romero’s Broadacre City renderings can be found in the Fall 2021 issue of the Frank Lloyd Quarterly Magazine. The Quarterly publication is an exclusive member benefit.

Learn more about becoming a member of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Jennifer Gray is an architectural historian and curator, with a special emphasis on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. She teaches in the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and preservation at Columbia University and is the former curator of Drawings and Archives at the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library. She studies modern architecture and how designers and activists used architecture, cities, and landscapes to advance social and spatial justice at the turn of the 20th century. She recently curated two exhibitions on Wright, including Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: unpacking the Archive at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her work has been published in journals of architectural history and critical heritage, and she is developing a book project on the Chicago architect Dwight Perkins. Gray recieved her PhD from Columbia University.

David Romero is an architect and 3D artist who lives and works in Spain. His work recreating demolished and unbuilt works by Frank Lloyd Wright has been widely celebrated in the field of architecture.

![[Cohen House Tropical Foliage (Abstract Pattern Study), Eugene Masselink, ca. 1957, graphite, ink, and paint on plywood, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Collection, 1910.223.2.]](https://franklloydwright.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/1910.223.2-2-a-320x240.png)