Don’t let the language of your community get stale

When we build communities, we establish cultural norms - the ways people interact with each other within that community that make it unique and sustainable. These help attract the right kind of participants to your group and offer a tangible model for the interaction you want to see more of. If your community culture has a problem (e.g. trolling and bullying), it’s likely those norms were never intentionally or consistently forged.

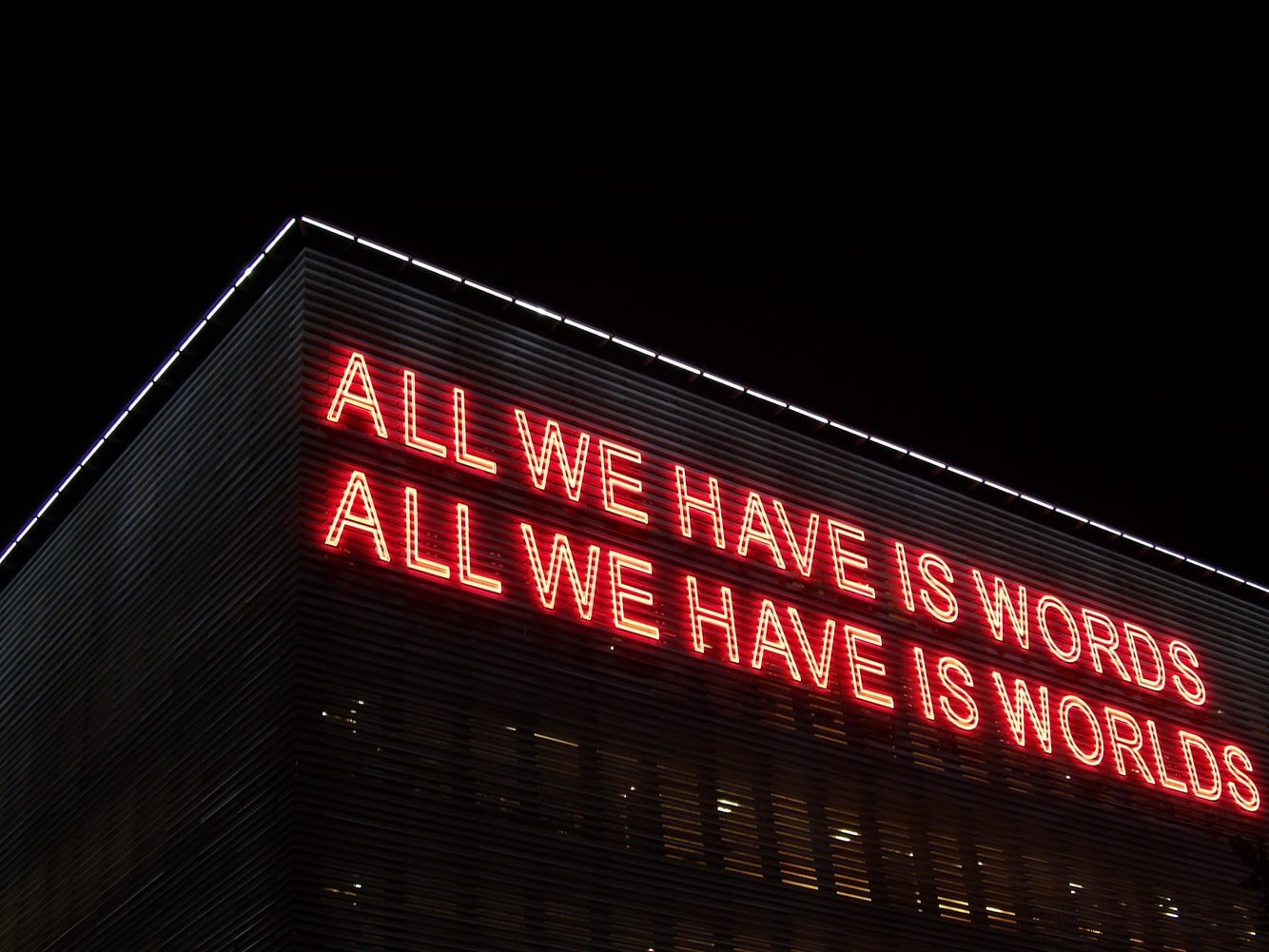

One of the norms we bed down is language - words or terms a community uses that act as its secret handshake, deepen sense of belonging, and help a newcomer navigate that community at a glance.

Think of it this way. If you were writing a User Manual for your community, what terms would it contain unique to your community context? What words or emojis are used as short-cuts? Is the language mainly visual, e.g. gifs and memes? Are there rituals the community performs regularly involving particular words or phrases?

If you’ve ever returned to a favourite community after an absence, the ways participants use language can feel like a homecoming - a warm blanket of familiarity that immediately resonates. But take care, or that comfort can eventually to apathy.

Research from Cristian Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, Robert West, Dan Jurafsky, Jure Leskovec and Christopher Potts (studying user language in an online beer tasting community) underscores the importance of cultural norming from the outset, and in evolving community language so it doesn’t become stale.

Their work reveals three key insights for community builders:

Users are most susceptible to taking on new norms early in their community involvement;

The more flexible a new community user is in adopting the language of a community, the longer they’re likely to remain in that community over time;

When a user becomes linguistically stale to new language norms or routines, it is a reliable indicator of likely community departure (regardless of whether they’re contributing a lot or a little in terms of post volumes).

So what does this mean for existing community management practice?

Firstly, it’s evidence to support proactive cultural norming as early as possible in our communities. If we only let norms emerge organically from the group, they risk hijacking by participants who don’t have the community interests at heart.

Secondly, it introduces the idea of linguistic state to community health; assessing the proliferation and adoption of language norms can be a predictor of user stability. Are new members ‘speaking the language’? If not, how can we help them do so?

And lastly, it emphasises the importance of language evolution over time within our communities. While norming is essential community management work to prevent risk and build healthy interactivity, core community artefacts like language must be allowed to evolve after initial establishment, with participant input. This should both deepen sense of community, while guarding against the linguistic fossilisation we now know can drive a user away.