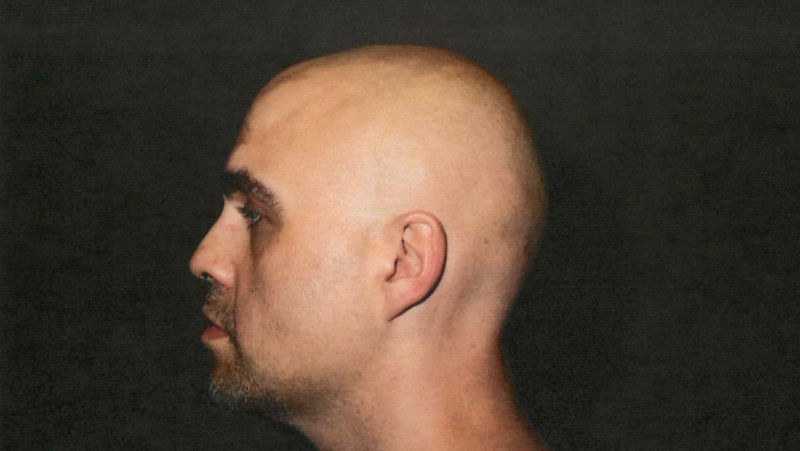

'You want to have hope for them': Edmonton police unit dedicated to helping high-risk offenders

The Edmonton Police Service regularly issues alerts about high-risk offenders who are being released into the community.

High-risk offenders are typically people who have finished serving their sentence but have been deemed a high risk to reoffend, officials say.

Usually they have been convicted of aggravated assault, aggravated sexual assault or child luring.

It's a different distinction from a dangerous offender, which is a designation sought by the Crown prior to sentencing for a criminal offence.

When a high-risk offender is released, EPS has a dedicated unit to supervise them, the Behavioural Assessment Unit (BAU).

Detectives John Smith and Jamie Irvine are two of the three officers in that unit. They sat down with CTV News Edmonton to talk about their work.

"We focus on supervising and managing the highest-risk offenders released into Edmonton," Irvine said. "As offenders transition from being incarcerated, usually on like long, long sentences, we're sort of like the in-between, as they're released into the community."

The offenders are released on a peace bond, which tends to last one to two years and comes with a list of conditions they have to meet.

"They have to live at approved addresses and then there's the basic curfew. No alcohol, no drugs, no weapons, depending on whatever their crime was," Smith noted.

STARTING OVER

For many of their clients coming out of prison after years inside comes with challenges above and beyond those conditions.

"A huge hurdle for us, honestly, is like, where are we going to find a place for them to sleep?" questioned Irvine, who says most offenders come out of prison with no money and no source of income.

"Everything needs an application, everything takes time. It's always hurry up and wait. And these guys need it right away, so we have to rely on some of our community partners like Salvation Army and Hope Mission for immediate housing," Smith observed.

After the offender is settled, they must meet with members of the BAU regularly as outlined in their peace bond.

"In my initial meeting with somebody who I'll be assigned to I just focus on building rapport from the beginning," Smith said.

"These offenders have had many, many police experiences throughout their lives. And they don't trust the police, obviously. So I kind of lead off with just telling them that 'I will never lie to you. I will tell you straight every time. And if you mess up, you mess up, and then we'll start again.'"

Both Smith and Irvine say they look at the job as an opportunity to improve public safety by intervening before an offender commits another crime, and hopefully helping someone get back on their feet along the way.

"I think knowing that we can have a positive influence in an offender's life and at the same time, the whole idea of BAU is that we maybe intercept a high-risk offender before there would be a new victim," Irvine commented.

"If we can pull one person kind of out of that lifestyle and be a positive influence, I see it as a win."

"When I first got into the unit, I was assigned an offender and working with that offender for the entire two years of his peace bond, watching him achieve each step and not reoffend at the same time, and then complete the full two years.

"That two-year mark was exciting. That was one of the most rewarding things so far for me," Smith recalled.

Both officers say they tailor their approach to each client to help them find success.

"If I have someone coming out and I know addiction is part of their crime cycle, I'm going to want to at least talk to them, but probably even see them as much as possible," Irvine noted.

"Most of the time, I can recognize if someone's intoxicated. So if I know that's what sends them down the slippery slope I can just deal with it right away."

He says he also takes the time to learn about their personalities.

"You're just learning about who they are and how they're gonna react. Some guys, you almost need to be that dad, you know, 'I'm disappointed in you.' They need to hear that and that's how you get the best response."

He adds many of the clients just need someone to talk to.

"It's surprising actually, how many phone almost daily, even though maybe we're not asking them to. It's almost like they want to talk to us," he said. "There's even detectives that were in BAU and have now gone and they're still getting phone calls from these people, because you can't help but kind of build a rapport and relationship with them."

"They may not have ever had a stable person in their life, ever. And so having somebody that they can call and they know will answer the phone is a big deal," Smith added.

The unit also relies on electronic monitoring and curfew checks to make sure offenders are staying within the boundaries of their conditions.

FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH CONDITIONS

But not everyone reaches the end of their peace bonds without reoffending.

"If the offender messes up and goes back to jail, our main goal is that they haven't messed up in a way that that initial violent crime has happened again," Smith explained.

"If they breached their conditions, and they have to go back to jail for a little bit, that's OK. It's not as bad as if they've re-offended violently."

Irvine notes it can be frustrating to see a person reoffend and go back to jail, but they have to manage their expectations.

"It's kind of like having that balance, where you want to have hope for them. But if they fail, you can't be too upset about it."

Irvine and Smith say the ongoing discussions in Canada about bail reform doesn't impact the work they do.

"We're dealing with the highest-harm individuals and almost 100 per cent of the time they're doing their entire sentence from day one until release. They don't qualify for that early release based off a lot of different factors," Smith commented.

"So bail reform or not, it doesn't kind of affect our clients."

And to those who don't believe in rehabilitation, they have this to say:

"An offender is gonna get out of jail after they've committed their crime. And at some point they'll be released back into the community. I can be positive and assist with their reintegration back into that community and do it with a positive outlook," Smith stated.

"I think it's important to say it doesn't mean we don't hold them accountable," Irvine added.

"We're police officers. So at the end of the day, if they commit a crime, we deal with it."

With files from CTV News Edmonton's Nav Sangha

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

'Most of the city is evacuating': Gridlock on Alberta highway after evacuation order in Fort McMurray

Four Fort McMurray neighbourhoods were ordered to evacuate on Tuesday as a wildfire gets closer to the city.

Sask. police seize 1.5M pieces of evidence, lay 60 more charges in child exploitation case

Saskatchewan RCMP have revealed that a historic sexual assault investigation has led to the discovery of alleged crimes against children dating back to 2005.

'Inappropriate' behaviour shuts down Dublin to New York City portal

Less than a week after two public sculptures featuring a livestream between Dublin, Ireland, and New York City debuted, 'inappropriate behaviour' in real-time interactions between people in the two cities has prompted a temporary shutdown.

Bouchard scores late to lift Oilers over Canucks, tie series

After a final frame that saw the visiting Vancouver Canucks claw their way back and tie the game late, a point shot by Oilers defenceman Evan Bouchard with 38 seconds left (until what seemed like certain overtime) iced the 3-2 victory for Edmonton to knot the series.

Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker rails against Pride month, working women in commencement speech

Kansas City Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker railed against Pride month, working women, President Biden's leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic and abortion during a commencement address at Benedictine College last weekend.

King Charles III unveils his first official portrait since his coronation

King Charles III has unveiled the first portrait of the monarch completed since he assumed the throne, a vivid image that depicts him in the bright red uniform of the Welsh Guards against a background of similar hues.

Full List Are these Canada's best restaurants? Annual top 100 list revealed

The annual list of Canada's top restaurants in the country was just released and here are the places that made the 2024 cut.

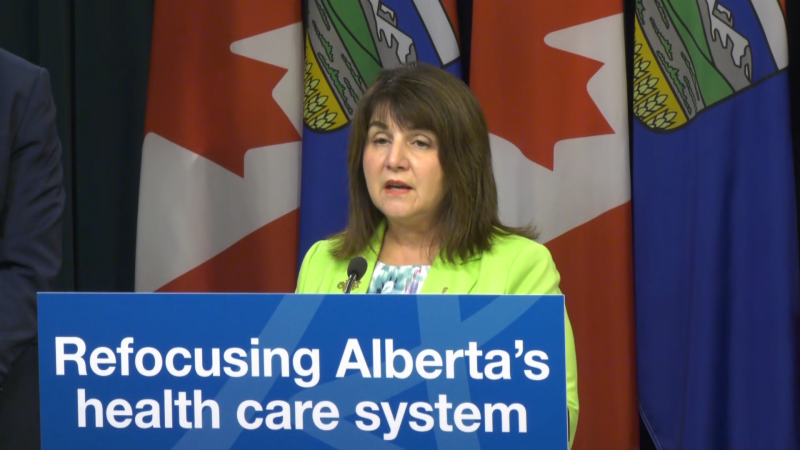

Alberta announces the 4 health agencies that will replace AHS later this year

The province has released more information on its plan to break up Alberta Health Services and replace it with four sector-based health agencies.

Biden administration moving ahead on US$1 billion arms package for Israel, AP sources say

The Biden administration has told key lawmakers it is sending a new package of more than US$1 billion in arms and ammunition to Israel, two congressional aides said Tuesday.