New research published yesterday reveals that putting your trust in Extended Validation ("EV") SSL certificates will not safeguard you from phishing sites and online fraud.

SSL certificates have become quite a common occurrence on the Internet. According to Let’s Encrypt, 65% of web pages loaded by Firefox in November used HTTPS, compared to 45% at the end of 2016.

Anyone can get a free or paid SSL certificate to secure a website via HTTPS. A report released by Phish Labs last week shows that one in four phishing sites currently loads via HTTPS.

EV certificates deployed in 2007 to fight phishing

The people behind the SSL industry knew this abuse was eventually going to happen, albeit they did not know when.

This is why they came up with the concept of "Extended Validation Certificates" in 2007, which are special SSL certificates that are only granted to companies that go through an extended verification process —standardized in the Extended Validation (EV) SSL Guidelines.

These extra verifications include additional paperwork that would create a more extensive paper trail, something that most crooks wouldn't risk leaving behind.

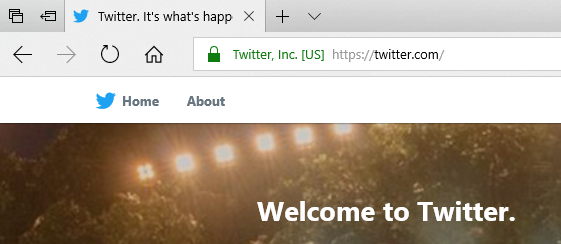

On the other hand, companies that obtain an EV certificate get a reputational boost. In recent years, browsers have started showing the company's name inside the address bar, as a way to reinforce and guarantee the site's identity to users.

EV certificates abused for phishing purposes

But things have drastically changed from 2007 to 2017. The plethora of recent data breaches has flooded the Dark Web with stolen identities.

Back in September 2017, a security researcher named James Burton created a fake company named "Verified Identity."

Through his research, Burton highlighted a flaw in the EV browser trust model that fraudsters could abuse. He theorized that fraudsters could use stolen identities to create fake companies with names that advertise personal safety. The fraudsters could then obtain an EV certificate for their fake company and host phishing sites on websites that show the classic HTTPS green lock and safe words that encourage users to believe they're on a legitimate site.

New research shows even a better way to abuse EV certificates

Yesterday, another security researcher named Ian Carroll took Burton's research to a whole new level when he realized there's no name collision support for the EV issuance process.

Carroll says that a fraudster could incorporate a new company with a name identical to a legitimate business.

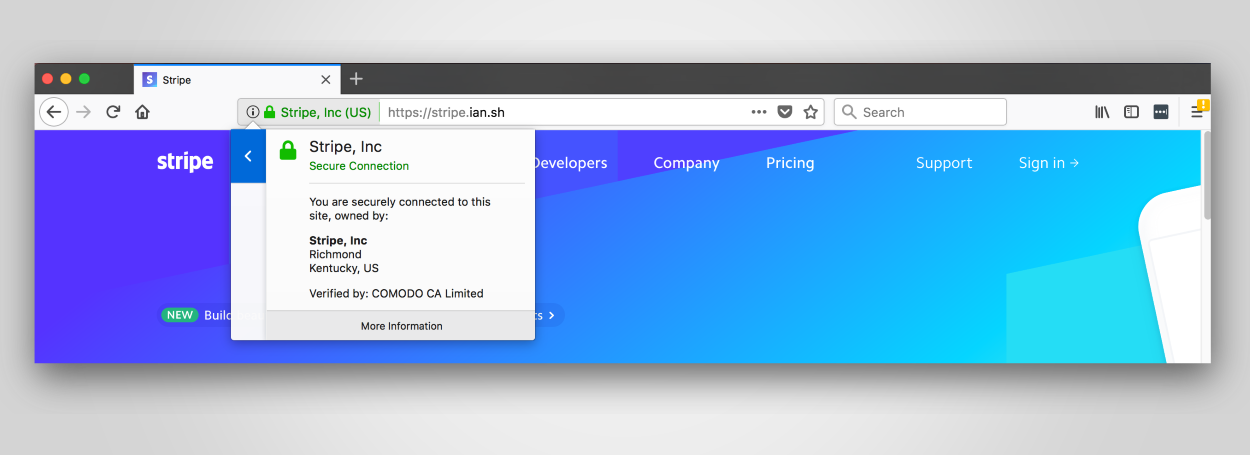

To prove his point, Carroll incorporated a new business called "Stripe, Inc" in the state of Kentucky, an intentional and obvious clone after the real Stripe, Inc (payments processor), which is incorporated in Delaware.

Just like Burton, Carroll had no difficulty in obtaining an EV SSL certificate. But there's a catch. Because of the identical company names, browsers would also pull and display the company's misleading name inside the URL bar, making the fake site look like a legitimate Stripe domain.

Carroll points out that some browsers will show the company's country code and other EV details such as state, city, or street address.

But let's be honest. Who in their right mind knows or memorizes where the real PayPal is incorporated just to fend off phishers.

"Neither of these [details] are helpful to a typical user, and they will likely just blindly trust the bright green indicator," Carroll says.

Furthermore, the situation gets even worse for some browsers. For example, Safari, on both desktops and mobiles, will hide the URL entirely, showing only the company name extracted from the EV certificate. Apple users have no chance at detecting phishing sites hidden under an EV-based, carefully chosen company name.

In addition, recent Chrome versions don't allow users to view certificate details unless they go to a specific location inside the browser's Developer Tools section. While Google engineers have promised to bring back the old certificate viewer, this still doesn't matter, as most users barely know that EV certificates exist and how they work.

EV certificates are definitely broken

Burton and Carroll's recent research shows that determined fraudsters have a solid trick in their sleeve when it comes to concocting convincing phishing pages.

Furthermore, the entire cost of obtaining an EV is around $177, with $100 for incorporating a US company and $77 for an EV certificate. The entire process takes two days and isn't as complicated as most people think.

While not all fraudsters will bother with setting up fake companies just to phish Google credentials, financially motivated crooks that stand to make millions of dollars by breaching banks or other high-value targets will go the extra effort to ensure their phishing pages look as convincing as possible.

"The primary point raised by advocates of extended validation is that obtaining EV certificates would leave behind a significant paper trail of the bad actor's identity," Corrall explains.

"However, there is minimal individual identity verification in the process. Dun & Bradstreet1 is the only entity who attempted to verify my identity, and did so with a few trivial identity verification questions. Purchasing identities with answers to common verification questions is neither hard nor expensive.

"Otherwise, there was no attempt at identity verification from the state of Kentucky or the registered agent I used in the process. This is typical of company formation in the United States. In summary, it would be trivial for bad actors to obtain these certificates," Carroll concluded.

Comments

fromFirefoxToVivaldi - 4 years ago

As for setting up another company with the same name, that may be the case in the US, but most European countries do not allow two companies the share the same name. The EV windows displays the country code, so people would know if it was registered in another country. On top of that, even in US this would require the phisher to set up a company to phish with, which means he'd be much easier to track and jail.

Mozilla is going to undermine the security of online banking in Europe because the US has some poorly designed laws and would allow a small windows of time between the phinishing starts and the website is shut down.

As for that Identity Verified example, this would also make it very easy to track the phisher, so if anyone actually attempted it, it would still be more beneficial to the potential victims.