The Emotes of Twitch

Watching livestreams of games is becoming an ever more common practice. Twitch.tv is the main place for watching these livestreams, as well as for interacting with streamers or other viewers. The interaction between Twitch users in chat channels, many of which can easily contain tens of thousands of viewers, is often accompanied by so-called ‘emotes’. This paper analyses three of these emotes as signs found in the vast linguistic landscape of Twitch’s livestream chats.

Introduction

Gaming used to be reserved for 'nerds', 'socially inept loners' and the 'guy living in his parents’ basement'. However, this stigma has changed in recent years. According to a survey taken in 2014 by LifeCourse, around 73% of Millennials played a video game in the 60 days before taking the survey. Add to that 62% of Generation Xers, and even the Baby Boomers picking up a game, with a little over 40% playing in the past 60 days and it's easy to see that gaming has become very commonplace. In fact, the results of the survey go on to show that gamers actually lead more social lives than non-gamers, indicating that the days of the 'guy living in his parents’ basement' seem to be over. As the popularity of gaming continues to grow, new phenomena tying in with this behaviour flourish. The biggest development? Streaming.

In many ways streaming is the prime example that the old stigma of 'socially inept loner' for gamers was wrong. Streaming refers to the act of playing a game while streaming said gameplay live on the internet. For a lot of young gamers, watching a ‘streamer’ play a game is the equivalent of watching TV for non-gamers. Hundreds of millions of people tune in each month to watch these streams. In contrast to watching TV, watching a stream is more often than not a very social act, as there is live interaction with the content being watched, namely with the streamer, and the rest of the audience. Every stream has its own chat channel that allows this interaction to happen.

With the most popular streamers having up to 30.000 viewers a day, these chat channels are nothing short of communities the size of small cities.

These communities consist of people with all sorts of different nationalities and native languages. The public place where all these multinational communities interact and place their semiotic signs can be called a ‘linguistic landscape’ (Blommaert, 2013).

This paper aims to look at the ‘linguistic landscape’ that are these chat channels, to determine how they function, what kind of signs are used, who uses them, and why. In order to do this, we shall first take a closer look at the overarching ‘place’ that allows this streaming interaction to happen: Twitch.tv, by far the largest streaming site for gaming-related content. Next, we shall take three signs found in the chat channels of three different Twitch streams and look in depth at how each sign is situated in its own ‘space’. Lastly, we shall look at these signs’ indexicality and how they tie together.

A town called Twitch...

Twitch.tv originates from the streaming website Justin.tv created in 2007. Justin.tv started as an online live broadcasting service, with all sorts of content. Users could stream their content for free, ranging from streams about their personal life, to makeup tutorials. However, as sites like YouTube grew and attracted a similar audience, it became clear that most of the content people were watching on Justin.tv consisted of games.

During this time, a lot of popular games were expanding their ‘eSports’ scene. ESports are games with a competitive professional league. Where conventional sports are shown on TV, eSports are predominantly shown on streaming websites. With the growth of eSports, as well as with recognizing their own userbase, Justin.tv changed to Twitch.tv in 2011, now primarily focusing on video gaming. Twitch.tv is now a center for individual gamers streaming for fun, large-scale streamers who make a living off of streaming their gameplays, with tens of thousands of viewers, as well as large organizations streaming professional eSports content to hundreds of thousands of viewers.

This results in 100 million viewers each month and 1 million streamers to watch.

75% of Twitch users are male, and 73% of them is in the age between 18-49 (Twitch Interactive, 2017). The fact that Twitch’s demographic is largely male is no surprise as the amount of female gamers, according to studies, seems to fluctuate between 18% and 41% (Yee, 2017; ESA, 2016). It is suggested that a lot of this variance is due to the genre of games. Since Twitch.tv doesn’t dictate what genre of game can be played, it could be that some genres might be less appealing to watch (such as farming simulators) or that it simply takes some time for these demographics to shift. When it comes to the nationalities of these viewers there isn’t a lot of available information. Since gaming is a worldwide phenomenon and you only need an internet connection to view a livestream we can, however, safely assume that the demographic is very much a multinational one. People from all over the world tune in to watch these streamers. While there are smaller streamers and some larger streamers that predominantly use their native language, English is the dominant language on Twitch.tv.

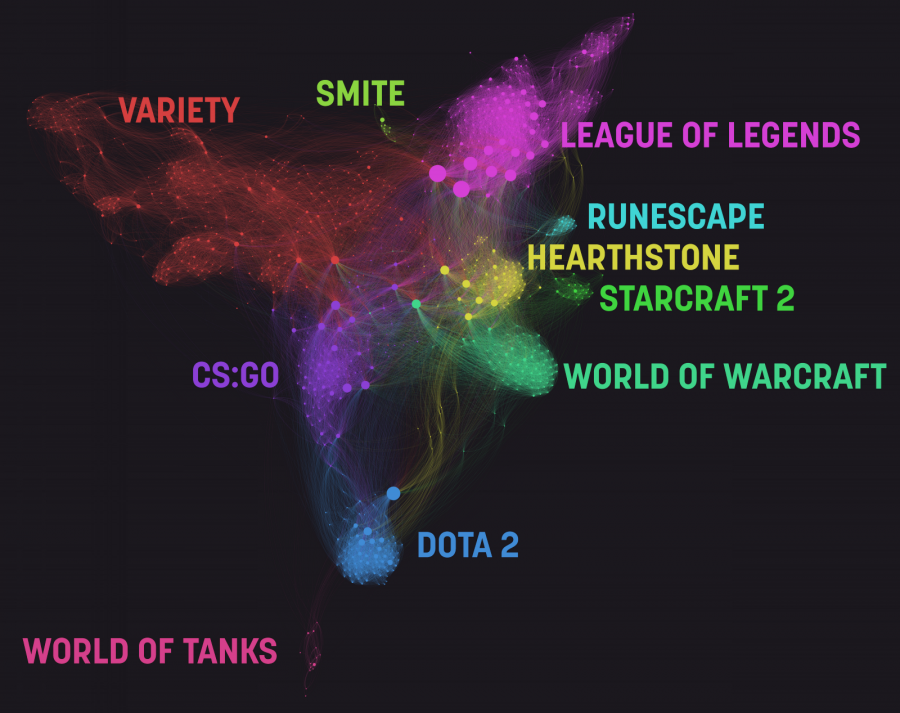

The English spoken in the chat channels is not, however, what one would call “standard English”. As Jan Blommaert puts it: “English ‘in’ a certain place – say, ‘English in Japan’ – needs to be understood as something that is a result of highly complex patterns of mobility, as well as an instrument for mobility – for ‘exporting’, so to speak, Japanese messages to other parts of the world.” (Blommaert, 2012, p. 2) So when we look at the ‘English’ spoken in Twitch's chat, we should really be looking at it like ‘English in Twitch's chat’. In fact, the English spoken in Twitch's chat is not only dependent on the different nationalities and native languages of its speakers, it is also dependent on the different jargons from the games being played in the respective Twitch chat channels. Therefore, the ‘English in twitch's chat’ is different when looking at ‘League of Legends’ chats (the most popular streamed game on Twitch) than when looking at ‘Call of Duty’ chats. Similarly to Blommaert's previous description, ‘League of Legends English’ could be used to ‘export’ League of Legends messages to other parts of Twitch, as well as, in a lesser part, the rest of the world. Twitch chat channels can therefore be very interesting examples of superdiverse communities. Figure 1 illustrates the diversity of communities on Twitch.tv (Star, 2015).

Figure 1. A visual mapping of Twitch and its Communities (Star, 2015).

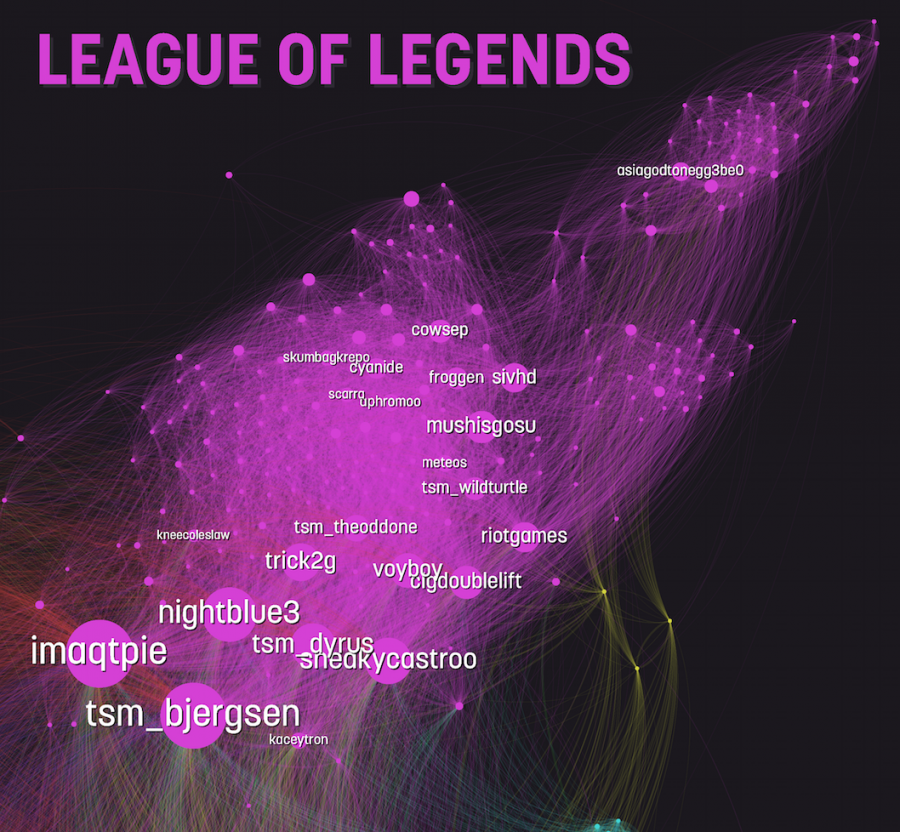

This visual map shows the different community clusters belonging to individual games and their relations to each other. The lines between these clusters are reinforced every time a specific viewer watches two different channels during a time period. The distance between communities therefore actually shows how often viewers from one game cross over to another. We can for example see that League of Legends viewers don’t often watch CS:GO streams and vice versa. When we look into one community, we can see how individual streamers attract viewers and how these viewers move around in the community. An example of this is shown in Figure 2 (Star, 2015).

Figure 2. Streamers and their viewer relations in the League of Legends community (Star, 2015).

In Figure 2 we can see that a streamer by the name of MushisGosu (visible near the center of the figure) has quite some concurrent viewers and a lot of his viewers only watch League of Legends, while a streamer by the name of imaqtpie, who is among those with the most viewers in this community, has a lot of viewers who also watch other games, i.e. they 'travel' over to other communities. This could indicate that imaqtpie has a very diverse group of viewers and his chat is therefore possibly a very interesting linguistic landscape.

As we have seen, Twitch.tv harbours a variety of large interconnected communities, with users moving easily between them. These users speak all sorts of English and mix these varieties between communities, Not only do Twitch's users come from all over the world (Twitch.tv, 2015), for example, and thus speak a variety of English specific to their own country, such as: 'English in Sweden' or 'English in Brazil', they also use community-specific English, such as: game-jargon and specificphrases. This is something we shall examine later on in this article. To look at speech differences between these communities could prove a difficult task, as some of these chat channels are filled with thousands of viewers. However, Twitch.tv also makes use of what is now a common phenomenon in digital communication: emoji. These emoji are used across Twitch and are particularly effective when there are a lot of viewers talking in a chat channel, since they are more easily recognised and understood than masses of text flooding through the chat. Linguistic landscapes are analysed by looking at the visible semiotic signs in its public space (Blommaert, 2012; Blommaert, 2013) and in this paper we will use these Twitch emotes as signs for analysing the linguistic landscape of Twitch.

The visual language of gamers

Emoji, or Twitch emotes as they are called on Twitch.tv, are, much like emoji, graphical representations of an idea or emotion. Different from most modern emoticons or emoji however, is the fact that the majority of Twitch emotes have a history behind them. In fact, the only emotes that have been, and continue to be added, apart from the quite standard emoticons like ‘:)’ and ‘;p’, are emotes with significant history in one or multiple communities of Twitch. With more than 170 Twitch emotes, this makes for a rich history of signs in Twitch communities, and this is only considering the official, free-of-charge, Twitch-wide emotes. Every streamer can create his or her own emotes, available only to viewers that have “subscribed” to the respective streamer. Subscription involves paying €4.99, €9.99 or €24.99 a month, to support the streamer, whilst getting access to special subscriber badges, emotes and other subscriber-only goodies, as well as being able to watch the livestream without any advertisements. The amount of personal emotes that can be created by a streamer depends on the number of active subscriptions this person has, starting with two emotes for someone who doesn't have any subscribers and ending with 50 emotes for 7000 subscribers and more. This means that there is a huge amount of possible emotes on Twitch. These subscriber emotes can be used in the chats of other streamers too, not just in the chat of the streamer one subscribed to, meaning they can be used as powerful tools in the sociolinguistic arena. In this paper, however, we shall look at three Twitch-wide emotes, partly because of the sheer amount of subscriber emotes, and partly because we are primarily interested in exploring the linguistic landscape of Twitch.

In the following sections we shall take a look at three different signs in the form of Twitch-wide emotes from three different types of streamers. These signs have been collected during livestreams of the respective streamers during a period of one week in June 2017.

Imaqtie Orc

The first sign (see Figure 3) we will take a look at is taken from the chat of League of Legends streamer Imaqtpie during one of his livestreams.

Figure 3. The SMOrc sign (TwitchEmotes, 2017).

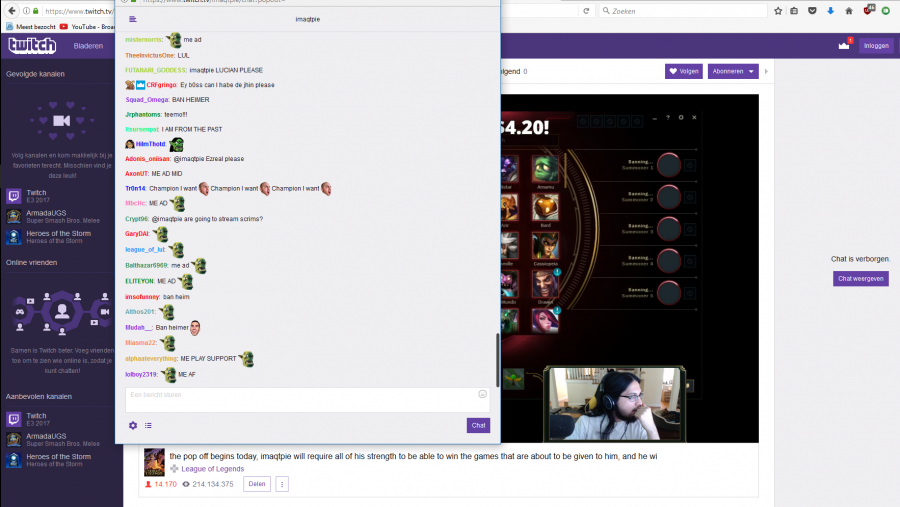

Imaqtpie is one of the largest streamers in the League of Legends gaming community, as well as in the whole of Twitch. With a regular viewer count of up to 30,000, he ranks as the 7th in follower count and 6th in viewer count on Twitch.tv. When looking back at Figure 2, we can see he is positioned at the edge of the League of Legends community. This results in his chat being a superdiverse community, as lots of viewers from different communities flock together in his stream. Imaqtpie started out as a small-time League of Legends streamer in 2010. A year later, he joined a team called ‘Rock Solid’ which, after some competitive success, was picked up by ‘Team Dignitas’, a large international eSports organization. After three years of playing with Team Dignitas, achieving moderate competitive success, he decided to become a full-time streamer. During his time as a professional League of Legends player, he became a big personality in the community, which allowed him to become one of the biggest Twitch streamers of all time. Even though he has recently joined a new professional League of Legends team called ‘Delta Fox’, he still streams regularly, attracting massive audiences. While he attracts a lot of viewers who also watch streamers in other communities, he almost exclusively plays League of Legends. It is therefore reasonable to assume that most of his viewers have some experience or knowledge of this game, even though they don’t exclusively watch these kinds of streamers. The sign we will take a look at is called ‘SMOrc’ and can be seen being spammed by viewers of Imaqtpie in Figure 4 .

Figure 4. The SMOrc sign being spammed by viewers during an Imaqtpie livestream (Twitch.tv/imaqtpie/, 08-06-2017).

SMOrc is an emote of the head of an orc from the game ‘Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine’ released in 2011. The SMOrc sign has been used 36 million times in the chat and is therefore, at the time of writing, the 13th most used emote on Twitch.tv (streamelements.com, June 2017). In the game ‘Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine’, the so called ‘Orks’ are one of the main antagonists. They are a violent race with a culture revolving around warfare. Orks typically have simplistic personalities, with more strength than brains. The SMOrc emote was originally used in the chat of ‘Hearthstone’ (an online card game) streams, when a streamer or his opponent was “going face” (Urbandictionary.com, 2017). In ‘Hearthstone’, a person wins when he or she destroys the enemy’s “face”, which is a slang term for the player’s hero, represented in the game by a portrait of said hero. The term “going face” therefore means to directly attack the opponent’s hero.

The nature of attacking someone in a direct frontal assault is most likely what attributed to the coinciding use of SMOrc, as this type of attack resonates with the nature and typical character of the Orks from “Warhammer 40,000: Space Marine”.

More recently, SMOrc is used as a way for the viewers in a chat to let the streamer know they want the streamer to do something, otherwise they will “riot”. In this case, for a chat to “riot” means users will spam the SMOrc emote. In Figure 3 we can see an example of this. A lot of viewers say the SMOrc emote in chat, seemingly indicating they want Imaqtpie to do something. At this point in the stream, Imaqtpie has to choose which character he will play for the next match of League of Legends. The game is a so called MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena) with two teams of each five players respectively, competing against one another. Each player has a specific role to fulfil, and Imaqtpie normally mainly plays the so called ‘AD’ (attack damage) role. However, in this game he was assigned the role of ‘Support’, and the viewers in his chat use the SMOrc emote to indicate that they want him to play ‘AD’. To try and force playing your preferred role, and forcing others to play your role, after these tasks have already been randomly assigned is seen as very rude and disrespectful in the League of Legends community. This type of bullying behaviour resembles the strength-focused, simplistic nature of Orks, and in turn the character of the SMOrc sign. It is interesting to see how there are two levels of meaning here: the first level of the SMOrc sign usage observed is the ‘standard’ meaning, i.e. the viewers demand something of the streamer, namely for Imaqtpie to play ‘AD’. The second level, however, is the usage of the SMOrc sign as a way of parodying the streamer’s own behavior. When we see some of the viewers saying: "me ad”, they essentially humorously mimic the behavior of Imaqtpie asking his teammates to change roles. This creates an interesting dynamic, as the first type of usage addresses the streamer, while the second type primarily addresses itself; namely the rest of the chat.

Joverainbow

The second sign, Kappapride (see Figure 5) is a popular variation on one of the most characteristic and famous Twitch emotes: Kappa (see Figure 6).

Figure 5. The Kappapride sign (TwitchEmotes, 2017).

Figure 6. The Kappa sign (TwitchEmotes, 2017)

While Kappapride is used a hefty 35.7 million times, ranking it as the 14th most used Twitch emote, the original Kappa is used almost 200 million times at the time of writing, making it the number one most used Twitch emote (streamelements.com, June 2017). In order to understand the origins and nature of Kappapride one therefore inevitably has to look at the origins of Kappa. The Kappa sign is based on a black and white version of a photo of former Justin.tv employee Josh DeSeno. Josh was assigned the task of working on the chat client of Justin.tv and since there were already many faces of Justin.tv staffers available as emotes, he decided to create one for himself. DeSeno decided to name his creation ‘Kappa’, which refers to a turtle-like water demon in Japanese mythology. A Kappa enjoys mischief and playing games. They have a proud, stubborn and fiercely honourable character (Yokai.com, 2017). Similar to the western ‘Troll’, Kappa have been used to warn children about the dangers of lakes and rivers, as they are sometimes said to lure victims into water to drown them. DeSeno had an interest in Japanese mythology, but did not create the sign specifically with the mischievous, tricking character of the Kappa in mind (Goldenberg, 2017). After its realease, the sign quickly became popular. During this time the core of the modern interpretation of the sign was established. Some people caught on to the original character of the mythological Kappa creature, others simply interpreted the smirk on the face of DeSeno as one of sarcasm and irony. The modern interpretation is not far off from that of the character of the Japanese water demon, as Kappa is quite often related to internet ‘trolls’ these days. As Kappa is most commonly used to express irony or sarcasm, internet trolls use it to trick people who don’t know the referential meaning of Kappa into believing that whatever the troll says was meant as truthful. Now that we understand the use of the Kappa sign, we can look at how a variation of this sign, Kappapride, is used. With the immense popularity of the Kappa sign, there have been a lot of spin offs over the years. Kappapride was introduced in 2015 in celebration of the same-sex marriage ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States. Since the rainbow colouring is a symbol of the LGBT pride movement, Kappa received a rainbow-makeover. Because of the nature of the Kappa sign, there were some concerns in the LGBT community on whether the interpretation of this sign was meant as a joke at the expense of LGBT community (reddit.com/r/gaymers, 2016). It seems more likely, however, that Twitch.tv simply wanted to use the Kappapride symbol as a way of expressing solidarity with the movement, as Kappa is the main symbol of their entire platform. To see how Kappapride is actually being used we take a look at Figure 7, which shows the Kappapride sign in action in the chat channel of Brazilian streamer Jovirone.

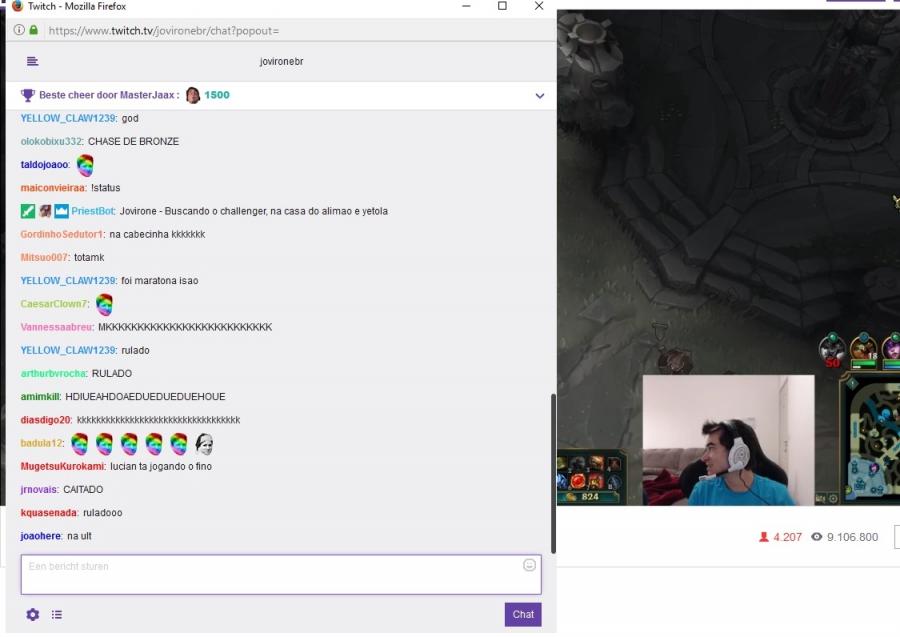

Figure 7. The Kappapride sign used in the chat of the Brazilian streamer Jovirone (Twitch.tv/jovironebr/, 10-06-2017).

Jovirone is League of Legends streamer from Brazil. He is a full-time streamer who has not had any professional competitive experience. He is, however, a very high-ranking player in the Brazilian region, which is one of the things that attract a lot of viewers. We chose to take a look at this streamer to see if in a chat where English is not the dominant language, emotes are still being used in a comparable manner. The Brazilian League of Legends community is quite a tight-knit community. They have their own League of Legends ‘region’, with their own Brazilian teams and competitive circuit. The viewerbase watching Jovirone is therefore likely a less diverse community than Imaqtpie’s. In Figure 7 we see that Jovirone’s champion had just died after having foolishly tried to chase down one of his enemies. This creates somewhat of an embarrassing moment for Jovirone as he looks at his chat to see how his viewers react and notices that they are making fun of him because of his mistake. Jovirone however, aware of his own silliness, is able to laugh it off. It is during this moment that viewers in his chat are using the Kappapride sign. When we take a look at the usage of the Kappapride sign in this situation, we can firstly see that it does not stray far from the usage of the Kappa sign. Since the viewers understand that Jovirone is aware of his mistake, they mock him by attributing him with the Kappa sign, marking his actions that of a ‘troll’, i.e. faking or joking around, even though his actions weren’t actual ‘trolling’. So why use 'Kappapride' when a simple 'Kappa' would’ve been enough? Since the actions of Jovirone were silly to begin with and he is clearly aware of this fact, because he laughed about it, it seems that the use of Kappapride is meant to signify an addition of silliness and frivolity to the original Kappa sign. This adds a layer of complexity to the usage of Kappapride, as the viewers do not simply use Kappa to mock Jovirone and his actions straight up, but also mock the silliness and awkwardness of the situation.

E3 Activated

The last sign we shall take a look at is the Jebaited sign (see Figure 8), added to Twitch in September 2016.

Figure 8. The Jebaited sign (TwitchEmotes, 2017).

This sign is slightly less popular than the signs we have analyzed so far; it isn’t ranked amongst the top 30 most used Twitch emotes (streamelements.com, June 2017). It’s created from a picture of Alex Jebailey; a director of Super Smash Bros.Melee/Brawl tournaments, most notably Community Effort Orlando (CEO). Even though Jebaily plays the ‘Smash’ games at an amateur level, he is known for having a huge ego, which makes him a well-known figure. Jebaited was created as a word play on Jebailey, and is often used to describe the video game tactic of ‘baiting’, which comprises of leading people on or luring them into something. ‘Trolls’ use the tactic of ‘baiting’ as well, when they try to make people react to them. The Jebaited sign is most notably used in the specific phrase or “copypasta” seen in Figure 9.

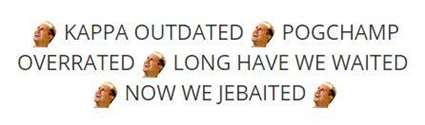

Figure 9. The “copypasta” called “Now We Jebaited”.

This phrase is a celebration of the sign Jebaited as it calls other, more popular, signs ‘outdated’ and ‘overrated’. When considering the large ego attributed to Jebailey, his smile in this sign creates the impression of Jebaited signifying some attained glory. This phrase can therefore be interpreted as a celebration not only of the Jebaited sign, but also of the repetition of the structure in which the phrase presents itself, indicating a glorification of the overarching emote culture on Twitch. To see how valid this interpretation is we take a look at the chat during a livestream of E3, the event for gaming news in the world. E3, or Electronic Entertainment Expo, is a very well-known event by gamers; however, the actual event is not open to the public and only allows 45.000 visitors. Due to the popularity of games around the world, in recent years E3 has created an event stream on Twitch.tv, temporarily creating an E3 streamers oriented community. With near to a million concurrent viewers watching this E3 community last year alone, it is clear to see how popular E3 is (Grubb, 2016). What's interesting for this paper is that this event attracts many different viewers from all types of communities, creating a superdiverse audience. This year, a variation of the phrase “Now We Jebaited” was spammed extremely often during the livestreams. In Figure 10, one such occasion can be viewed during the livestream of the press conference of Nintendo.

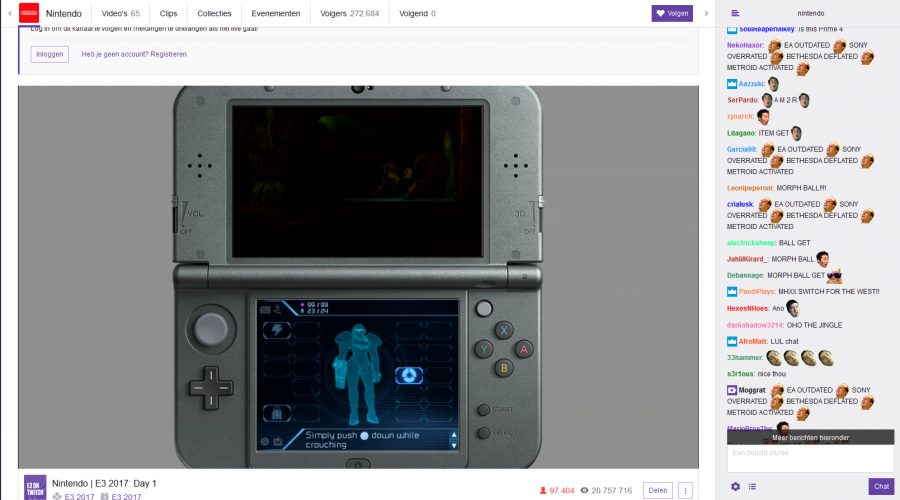

Figure 10. A variation phrase of the Jebaited copypasta being spammed during a Nintendo E3 press conference (Twitch.tv/Nintendo, 13-06-2017).

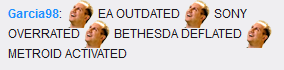

During this point in the press conference livestream, Nintendo is showing their new ‘Metroid’ game, a title that hasn’t had any new games for a long time. People in the chat seem to get very excited by this, and spam a variation of the “Now We Jebaited” phrase, as seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Variation of the “Now We Jebaited” phrase.

This variation calls other videogame publishers, who at this point already have had a press conference, ‘outdated', ‘overated’, and ‘deflated’, while lauding this new Metroid game; ‘Metroid activated’. One interesting dynamic that is observed in this livestream, is that there usually is one figure that represents the streamer who communicates with the chat and vice versa. Since there is no one figure that represents the Nintendo stream, the chat is essentially mostly talking to itself, and in doing so creating a shared meaning and identity that uses this phrase to express disappointment with previous press conferences, a sound approval of the current one, as well as a self-confirming glorification of Twitch chat’s own identity and culture.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to explore the linguistic landscape of Twitch's chat by investigating how it functions, what signs are used in these chats, as well as who uses them and why. An exploration of the diverse communities of Twitch showed a vast linguistic landscape of millions of inhabitants moving through them. An analysis of signs used in these linguistic landscapes showed three very different signs. These three different signs did, however, have one thing in common: they all contained an element of mockery and humour. SMOrc was used by the Twitch chat to mock Imaqtpie’s modest request to his teammates for his preferred role, Kappapride was used to mock Jovirone for his silly mistake, and the Jebaited phrase was a mockery of the ego of a community figurehead, as well as the mockery of half the gaming industry. It could be interesting for future research to try and find signs that do not share this element and investigate their usage in Twitch communities. Apart from this common element, every sign was used in a different way. The SMOrc sign was used as a tool to indicate a demand made by the chat towards the streamer. Kappapride was used as a variation of another sign, in order to express a situation in a more nuanced way than would have been possible with the original sign.

It showed how able a chat was at using these signs and creating new meaning for them in varying situations.

Not only was a chat able to interact and express meaning towards the streamer, using signs, it was also able to forge a temporarily shared internal identity. This was clearly observed with the “Now We Jebaited” phrase. The Jebaited sign fused within the structure of the phrase, formed a complex, flexible sign of its own. It was adapted by the chat during the Nintendo press conference to express personal opinions, but also to create a unity, as hundreds and thousands of participants repeated the phrase. This was a clear example of a shared culture of signs in the linguistic landscape of Twitch. While many signs were universally adapted across Twitch, some signs did indicate a specific origin of the speaker: the Jebaited sign originated from the ‘Smash’ game community, as well as a huge amount of ‘subscriber emotes’, which are only available to those who subscribe to the respective streamer. As signs change and adopt new meanings as viewers move from community to community, it seems that Blommaert’s (2012) description of language as something happening in a ‘place’ is very accurate for Twitch. It is perhaps no wonder these signs are very popular when a Twitch chat can easily have 10.000 participants. With such large amounts of participants, text becomes hard to track, thus promoting the use of signs. As gaming becomes more mainstream, and Twitch continues to grow bigger and bigger, signs will continue to be added, adapted, and changed. Their meaning will change and shift in an ever changing, vast linguistic landscape. One thing, however, could remain a constant in this landscape: there is a good chance the users of Twitch will find a way to mock people with every single one of the emotes available to them. And honestly, who can blame them; they are above all simply a lot of fun.

References

Blommaert, J. (2012). Sociolinguistics & English Language studies.

Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, Superdiversity, and Linguistic Landscapes. Bristol, U.K.: Multilingual Matters.

Entertainment Software Association (2016). Essential Facts about the Computer and Video Game Industry.

Grubb, J. (2016, June 13). Twitch’s E3 livestreams watched by a staggering 925k concurrent viewers.

Goldenberg, D. (2015, October 21). How Kappa Became The Face Of Twitch.

LifeCourse Associates (2014, June). The New Face of Gamers.

Reddit.com/r/gaymers (2016). A new emote on twitch.tv Kappapride!.

- SMOrc. (2017). Urbandictionary.com.

Stats.streamelements.com (2017, June). Top Twitch Emotes.

Star, E. (2015, February 4). Visual Mappings of Twitch and Our Communities, ‘Cause Science!’.

TwitchEmotes (2017). SMOrc.

TwitchEmotes (2017). Kappa.

TwitchEmotes (2017). Kappapride.

TwitchEmotes (2017). Jebaited.

Twitch Interactive, inc. (2017). Twitch Audience.

Twitch Interactive, inc. (2015). 2015 Retrospective.

Yee, N. (2017, January 19). Beyond 50/50: Breaking Down the Percentage of Female Gamers by Genre.

Yokai.com (2017). Kappa.