Hand-washing! It takes minimal effort and is incredibly effective, and yet we still don’t do it properly. In this time of COVID-19, we really ought to change that, James Hamblin wrote in the Atlantic last week, a desperate doctor’s plea for people to do better. “Many people remain dismissive of the most widely accepted, simple advice to slow the spread of most viruses,” Hamblin points out. Nobody, man, woman, or health care worker (yikes), hand-washes well enough.

What’s to blame for our collective failure to scrub for the prescribed 20 seconds, using plenty of soap and friction, after using the bathroom and before eating food? Hamblin suggests it might be America’s “general history of focusing less on evidence-based preventive behaviors than on billable treatments.” Sounds reasonable. But it’s also worth noting that there is a consistent gender gap in hand-washing practices. That gap is self-reported: A survey of American men and women, taken in 2018, asked whether particular hygienic behaviors were important—changing your underwear every day, washing your hands after using public transportation, sanitizing living spaces—and found gender gaps between 8 and 10 percentage points. Researchers see this when they make observations in public spaces, too. In 2003, a study of travelers in North American airports found that 83 percent of women hand-washed after using the restroom, versus 74 percent of men. In three surveys taken between 2005 and 2010, observers watched visitors to restrooms at big public attractions like museums and stadiums in Atlanta, Chicago, New York City, and San Francisco, and discovered hand-washing gender gaps ranging between 16 and 25 percentage points. One study from 2003 even found that a simple sign posted in a campus restroom urging hand-washing greatly increased compliance among women, but did nothing for men.

The hand-washing gap is a gender difference that has a history. There was a horrible window—between the acceptance of germ theory in the late 19th century and the decline of mortality from infectious diseases (thanks to sanitation, vaccines, and antibiotics) in the middle of the 20th—when American women were told that their families’ health depended on them enforcing the strictest standards of hygiene. In her book The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life, historian Nancy Tomes describes the immense pressure on women that the new knowledge of germ theory produced.

The late 1800s were a distressing time for women charged with preventing disease through hygiene. Scientists were learning where many deadly diseases really came from, before figuring out how to prevent or treat them with vaccines or medicines, and messages about the many sources of infection had to have been completely panic-inducing. A 1874 editorial in the reformers’ journal the Sanitarian described all of the parts of the home that could make people sick. It’s a forbidding list: “From the cellar, store-room, pantry, bedroom, sitting room and parlor; from decaying vegetables, fruits, meats, soiled clothing, old garments, old furniture, refuse of kitchen, mouldy walls, everywhere, a microscopic germ is propagating.” After Robert Koch proved that tuberculosis was infectious, and not hereditary, the activist National Tuberculosis Association blitzed people with warnings about contacts in daily life that could spread infection. One example: A National Tuberculosis Association article from 1910, called “Little Dangers to Be Avoided in the Daily Fight Against Tuberculosis,” contained (Tomes writes) “a dizzying array of warnings against drinking cups, paper money, wooden pencils, the prick of an old pin, and the forks supplied at oyster stands.”

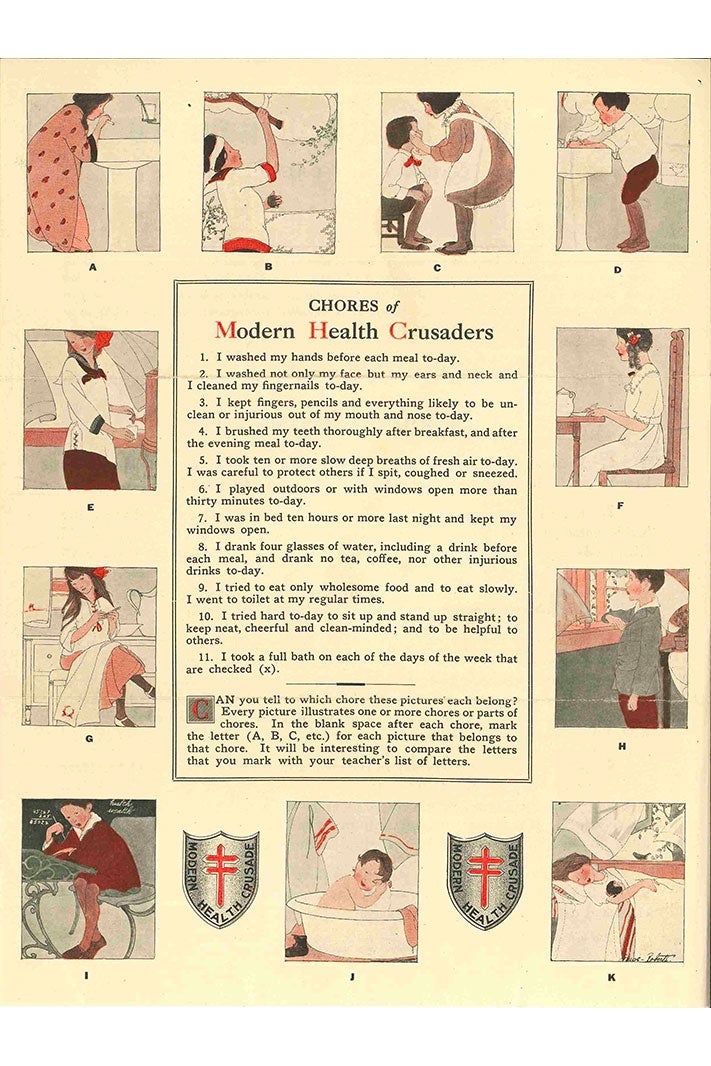

Women were always at the center of hygiene improvement efforts. The public health workers who went to tenements and farms to preach this “gospel of germs” as visiting nurses, social workers, and home economists were often women. And under this new way of thinking, mothers were supposed to be the role models for the entire family—teaching hand-washing, stopping men from spitting in the house, and keeping anyone from kissing their babies. The health department in Newark, New Jersey, sent a bib to every baby born in the city in 1929 that had the legend “I don’t want to be sick, please do not kiss me.” (This is a gift I suspect some contemporary parents would appreciate in this year of bad flu.)

The job of hygiene gatekeeper came somewhat naturally to Victorian women and their daughters, who were used to the expectation that they’d be the moral instructors of their households, but it could still be an unpleasant one. Tomes read correspondence between home economists and women who wrote that older family members mocked them for their new ideas, and refused to stop sharing spoons and plates with their babies or chewing bites of food before giving them to the infants. “Spitting also became a useful tactic for men to annoy hygiene-conscious ladies,” Tomes wrote, even after a full decade of anti-tuberculosis crusaders exhorting men to stop expectorating on the street, on public transport, and even (shudder) inside the home.

Before the introduction of better sanitary regulation of milk and food sold commercially, women were also the ones told to exert consumer pressure—to buy safe food for their families, while also forcing individual vendors to improve their sanitation practices. Home economists told women to choose stores that used individual packaging for food and get baby’s milk from dairies where dairymen were clean and washed their hands frequently—cost savings be damned. Women could use the power of their dollars to force more bakers and grocers to adopt hygienic habits, by avoiding the establishments where bakers allowed mice to run across their bread, or the groceries where cats lazed around on cracker barrels. And when women got the vote, they used it to fund the increases in public health spending that supported the intensive hygiene education campaigns credited with some of the midcentury’s great decline in child mortality, as Grant Miller has found. Voting women took the question of germ control seriously, and made it part of their politics.

A lot of this history can look kind of mockable, from a distance, because the advice sounds frantic, and some of it didn’t wear well. Sewer gas was not, contra Victorian belief, the cause of everyone’s maladies; library books didn’t need to be fumigated with formaldehyde between borrowers; clothing cannot transmit yellow fever; dark rooms don’t breed germs any more than sunlit ones do. But the history is also one of heartbreaking tragedy. The good news of germ theory, for women: Through aggressive sanitation and hygienic practices, it was suddenly possible to save many babies from the infectious diseases that had been the leading causes of death for the almost 2 out of every 10 children who died before age of 5 in 1900. The bad news for these women living after the age of knowledge but before the age of antibiotics: If the babies died in the future, it just might be their mothers’ unhygienic fault.

Many poor women, living in tenements and on farms, were in a terrible position: They had the knowledge, but not the resources, to address the problem of germs. A painful letter Tomes read, between home economist Martha Van Rensselaer and a farmer’s wife she encountered in her outreach work, showed that many women took this lesson of culpability to heart. “Our farm is neat and clean, all but the house, yard, and cellar, and my husband keeps that for refuse,” this wife, converted to Van Rensselaer’s gospel of germ control but unable to execute some of the changes she needed to make, wrote. “Even if I were capable of arranging it like a palace, so to speak, my hands are tied. … Men, men, mud, mud, and my cellar. I wonder we are alive. Poor me, I know if everything had been kept properly my children would be alive and well.”

Over time, what Tomes calls the “institutionalization of germ protection” fixed many of the problems homemakers in the early 20th century had been taught to control by dint of hypervigilance, obsessive cleaning, and meticulous consumer choice. By World War II, we had better hospitals, better municipal services, and more regulated food production to fall back upon. “Increasingly,” Tomes writes, “the housewife’s most important public health duties came to consist of immunizing her children and schooling them in the avoidance of contact infection.” As the century proceeded, fewer and fewer women lost babies to “summer complaint” (acute diarrhea), and the fear of infection faded somewhat. (Polio kept it alive until the announcement of a vaccine in 1953.)

But the legacy of homemakers’ early-20th-century germ anxiety persisted in the commercial sphere, where ads for cleaning products have kept the fear alive. A Lysol ad from 1929 asked “Are your door-knobs safe for little hands to touch?” and added, “No matter how thoroughly you clean, with soap and water, the places little hands touch, germs remain to do their deadly work—to spread the common diseases which every mother dreads.” In 1950, Lysol advertised with a photo of a woman holding a baby, and asked, “Why risk his health with temporary disinfectants?” playing on the long-outdated belief that household dust could carry “disease germs,” even in the “cleanest-looking home.” Even today, in its “Beds get sick too” TV ad, Lysol has scrapped most of the old fearmongering but retained the idea that it’s the mother who will get rid of “illness-causing bacteria” when a child’s bout of sickness is done.

This painful history of womanly responsibility for everyone’s health is still with us, but now it’s a shadow presence, showing up in things like the baffling differences between male and female standards of household cleanliness, and that persistent hand-washing gap. Here are a few examples from news coverage of the topic of hygiene and hand-washing that show just how entrenched the “naggy clean mom” archetype is: “Your mom probably scolded you for playing in the dirt, but doing so may be healthy” (U.S. News and World Report); “Somewhere between the Mom who obsessively wipes down every knob and toy her child might touch, and the Dad who thinks rolling in the dirt is ‘good’ for kids, there’s a healthy medium” (WebMD); “Does it take an outbreak of a frightening, potentially fatal infectious disease like SARS to get people to follow Mom’s advice to ‘wash your hands after using the bathroom?’ ” (EurekAlert!).

The answer: maybe yes. As for me, lately, I’m singing “Happy Birthday” twice, and making my kid do it, too.