Adelaide’s adventures with mid-century modernism

A new exhibition at the State Library brings to life a previously overlooked archive of Adelaide’s 20th-century architectural gems.

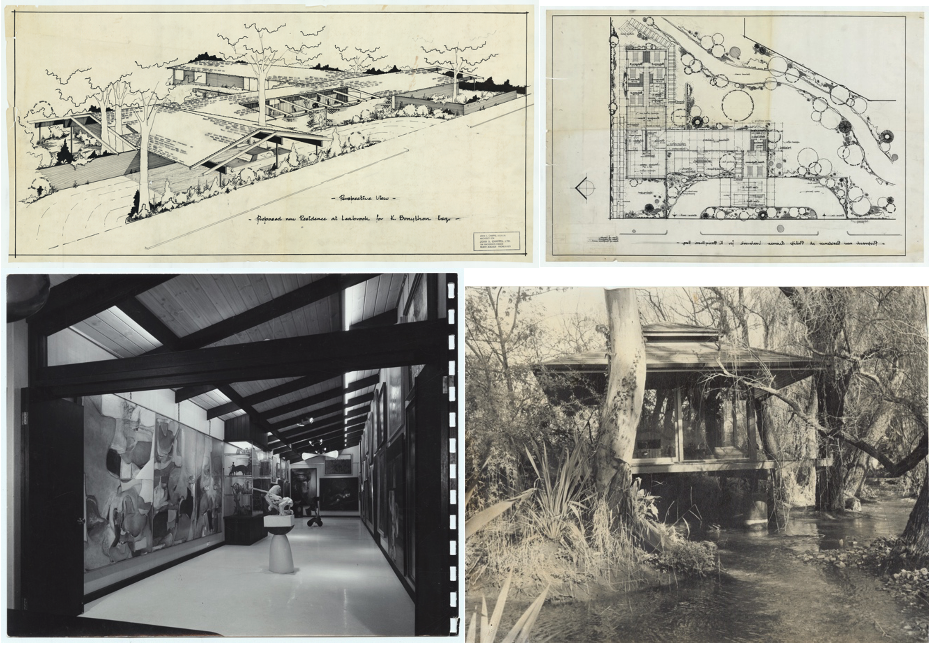

In a move typical of many in Adelaide’s fashionable elite, prominent local lawyer and literary figure Robert Clark left his sprawling Medindie home in 1961 to live in a John Chappel-designed house on 200 acres of secluded scrub at Montecute. Source: State Library of South Australia

Lust for lifestyle: Modern Adelaide Homes 1950-1965

State Library Gallery

Modernism first came to Australia in the early 20th century through migrants, expatriates, exhibitions, newspapers, magazines and books.

The theory and practice of modernist architecture was developed in North America by Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, then taken up even more passionately in Europe by Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius.

A common theme was the rejection of the traditional in favour of the practical. Interpreted differently at different phases of the movement’s lifetime, the mantra “form follows function” saw technology-enhanced minimalism replace historic stylism and decorative design.

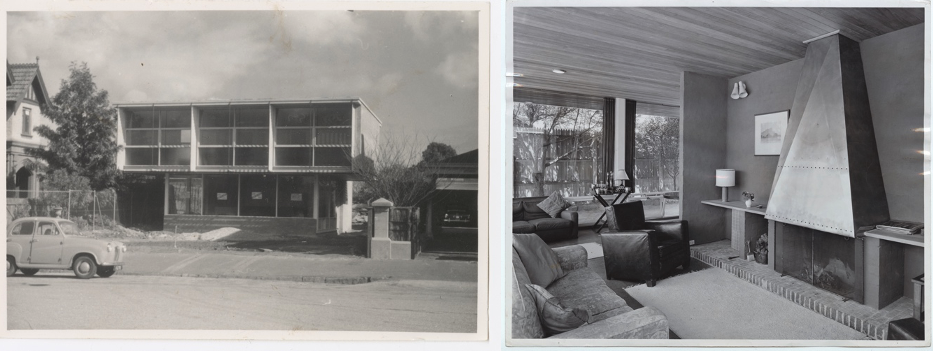

Adelaide architect and academic Gavin Walkley admired and respected his friend Robin Boyd so much he invited him to design his own home in 1956. Source: State Library of South Australia

These ideas found their way to Adelaide when Melbourne architect Jack Hobbs McConnell arrived here in a sports car in the late 1930s, immaculately dressed and accompanied by his boxer dog Blaze. McConnell led younger South Australian architects to embrace the “aesthetic of the unadorned”. John S Chappel, Jack Cheesman, George Lawson, Maurice Doley, Robert Dickson and Newell Platten were among those who started designing houses suited to function and climate, in harmony with their occupants and the South Australian environment.

As architectural correspondent for The Advertiser from 1956 until 1990, John Chappel is central to this exhibition celebrating Adelaide’s embrace of modernism – Lust for lifestyle: Modern Adelaide Homes 1950-1965 is based on the State Library’s extensive collection of his photographs and papers.

In tune with Robin Boyd and others in the Australian modernist movement, Chappel used his position in the media to advocate for a new Australian architecture “not borrowed from another land, but which belongs to our own country, conditions and time”. He was also adept at securing clients to support that vision.

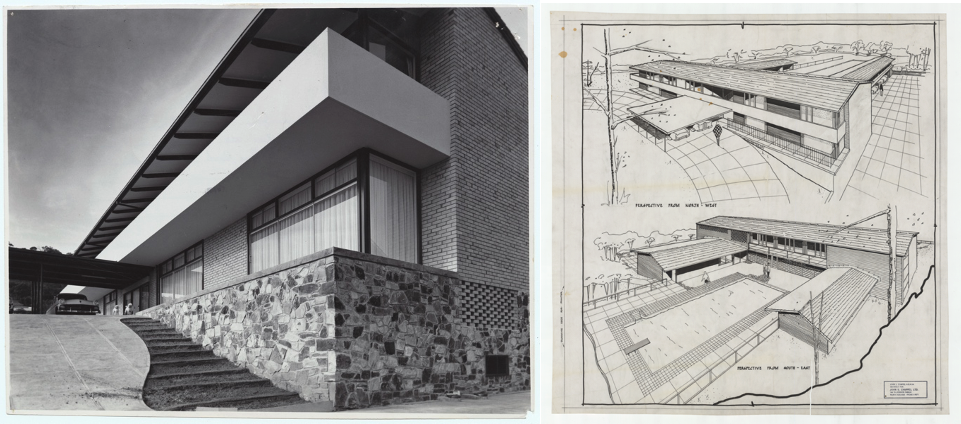

Having journeyed to Frank Lloyd Wright’s home ‘Taliesin’ in Wisconsin, architect Peter Muller emulated Wright’s interest in the horizontal at Michell House on Robe Terrace. Source: State Library of South Australia

According to Adelaide University academic and exhibition co-curator Dr James Curry, a booming post-war economy and emerging consumer culture created a new generation of socially mobile individuals who sought to define themselves through modern architect-designed homes.

“In contrast to the United States, where modernism became increasingly commonplace… modern architecture in Adelaide became associated with the social elite,” Curry explains. This was not only driven by the modernist aesthetic, but also by the allure of a less formal lifestyle, an appreciation of modern art and design, and a new awareness of the Australian landscape.

Bonython House (top and bottom left) and Cleland House (bottom right) are among the many designs in the exhibition that responded to the topography of an Adelaide creek bed – evoking Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic 1939 ‘Fallingwater’ residence. Source: State Library of South Australia

The names associated with the 15 houses showcased tell their own story. There’s the highly recognisable Walkley House on Palmer Place, designed by Robin Boyd for architect and academic Gavin Walkley; Peter Muller’s unassuming yet self-assured Michell House on Robe Terrace, commissioned by a member of the Michell wool family; and Bonython House on tree-lined Second Creek in Leabrook, designed by Chappel for jazz and art aficionado Kym Bonython. Chappel also completed barrister Pamela Cleland’s landmark house and garden at Waterfall Gully.

Successful merchants and migrants joined the ranks of established Adelaide families to embrace the modernist lifestyle, often choosing newly-established suburbs for their homes.

German migrant and importer Gunter Niggemann claimed his house at Tennyson (designed in 1953 by Lawson, Cheesman and Doley) wasn’t much liked by “mostly conservative” Australians, but that in professional circles it received a lot of attention. The house was remarkably in step with 21st-century climate-responsive design, featuring an open-plan living-dining area separated by a breezeway, a western beach aspect with rolling blinds, moving sight screen and adjustable louvres, aluminium and glass windows and concrete floors, and a prefabricated steel frame and roof trusses on a spaced regular module.

Internally, Niggemann House was furnished as a luxurious salon with plush seating, a grand piano and a collection of Chinese jade and ivory ornaments.

Niggemann House at Tennyson (Lawson, Cheesman and Doley, 1953) pre-dated Boyd’s 1956 Walkley House and was in step with contemporary climate response techniques. Source: State Library of South Australia

Scrap metal merchant Alfred Brown chose a north-facing double allotment in Springfield for his Chappel commission, which encompassed three large wings set around a large swimming pool. Described by Chappel as “the largest modern house in Adelaide”, it had seven bedrooms, each with its own dedicated bathroom, vanity bar and toilet, six garages to house the family’s car collection, a bar room, billiard room, dining room, living room and kitchen, with two stair halls, two galleries, a barbecue and swimming pool change rooms.

The double door access to Brown House in Springfield was marked by a ‘porte-cochère’. Originally designed for a coach and horses, it evolved into a sign of wealth celebrating car culture. Source: State Library of South Australia

Minimalism didn’t always win out in this context. Many of these houses embraced luxurious finishes and trimmings – from polished timber, solid brass fittings, marble furniture and fireplaces to the occasional chandelier. John Chappel’s documentation of modernism in Adelaide thus challenges the egalitarian associations of the movement elsewhere.

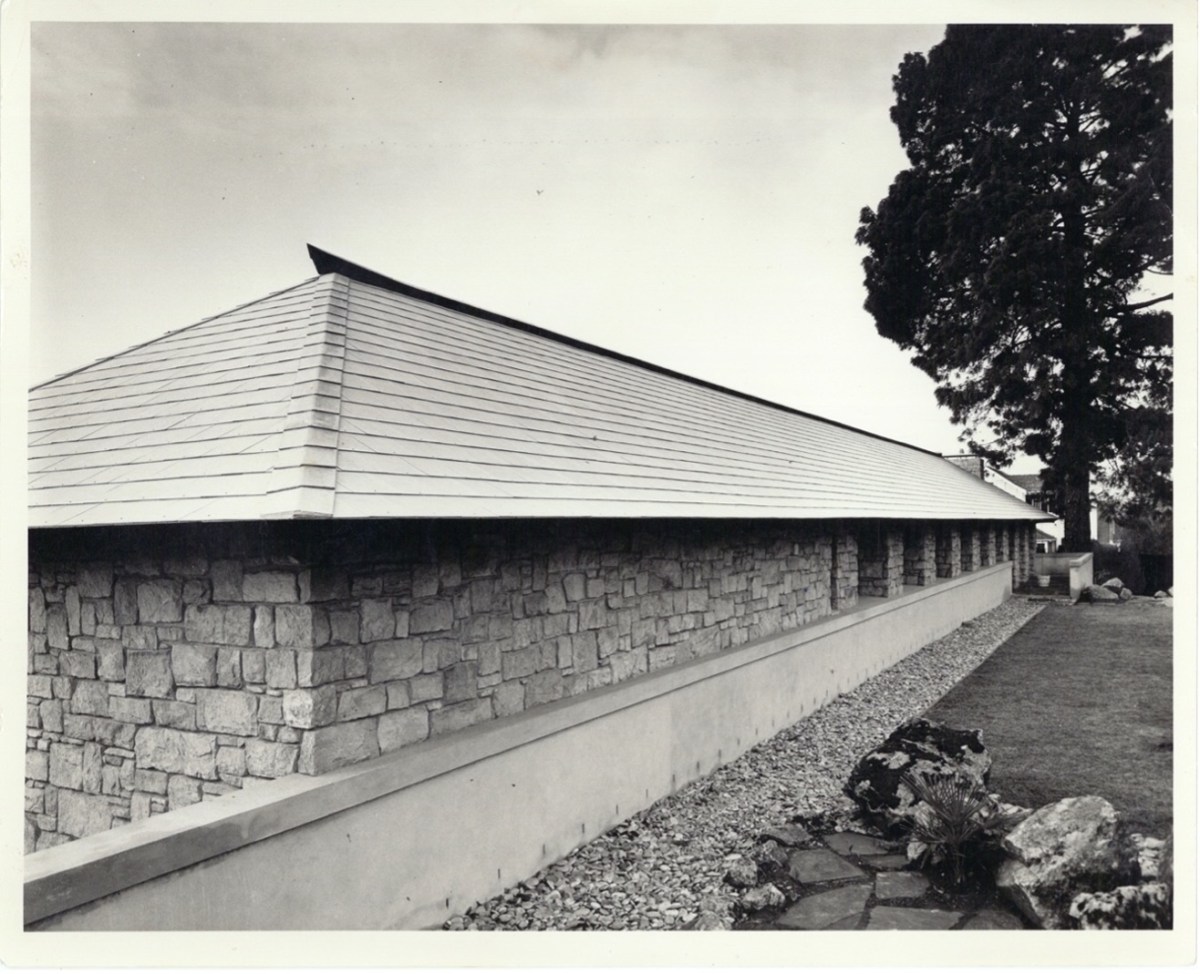

This 1954 home for Arkaba Hotel entrepreneur Istvan Zsolt at Eden Hills was one of Robert Dickson’s earliest projects. Source: State Library of South Australia

Robert Dickson’s design for Hungarian migrant and Arkaba Hotel developer Istvan Zsolt wasn’t overly large, but was nevertheless generous on many levels. Located in Eden Hills, with expansive views across the city to the sea, the house placed a strong emphasis on indoor/outdoor living and boasted a range of entertainment and leisure spaces including a rumpus room, tennis court, barbecue area, terrace, balcony, pergola and swimming pool – at the time a symbol of prestige and luxury.

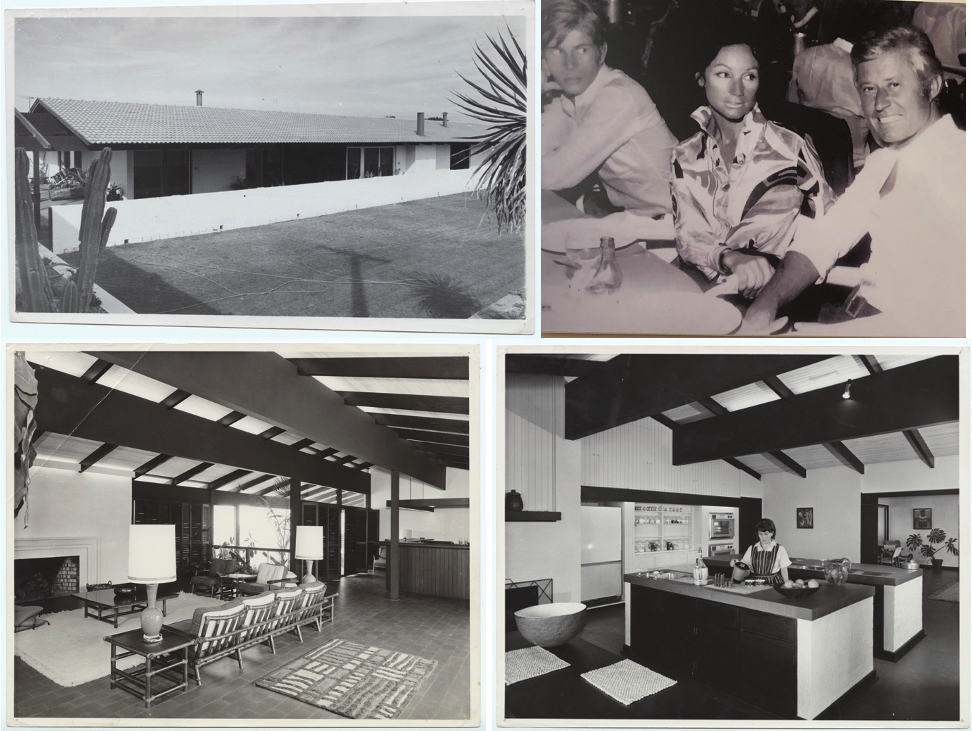

A heated courtyard swimming pool was the focus of family life in Chappel’s adobe ranch house design for celebrated Adelaide car dealer (and Robert Redford look-alike) Robert Billam.

The exhibition interview with the Billams’ live-in nanny, Jessie Plush, unveils a sophisticated lifestyle and a quality-not-quantity approach to the home’s pared-back design and furnishings. In contrast with the “porte-cochère” at Brown House, the motor-court entrance for Billam’s luxury car collection – including an Aston Martin, Ferrari, Mercedes, and Lamborghini – was concealed from view.

This ‘spectacular adobe ranch house’ on the Esplanade at North Brighton was commissioned by car dealer Robert Billam and his wife Andree (top right). The lounge was furnished with rattan furniture from US luxury department store Neiman Marcus, while an industrial-sized kitchen included dual ovens, garbage disposal, refrigerators shipped from the US, and a dishwasher. Source: State Library of South Australia

Billam House was only recently demolished to be replaced by a group of stock-standard concrete townhouses, while John Chappel’s design for his own office in North Adelaide faces a similar fate, highlighting the urgency for heritage listing in South Australia to turn its attention to these fast-disappearing 20th-century gems.

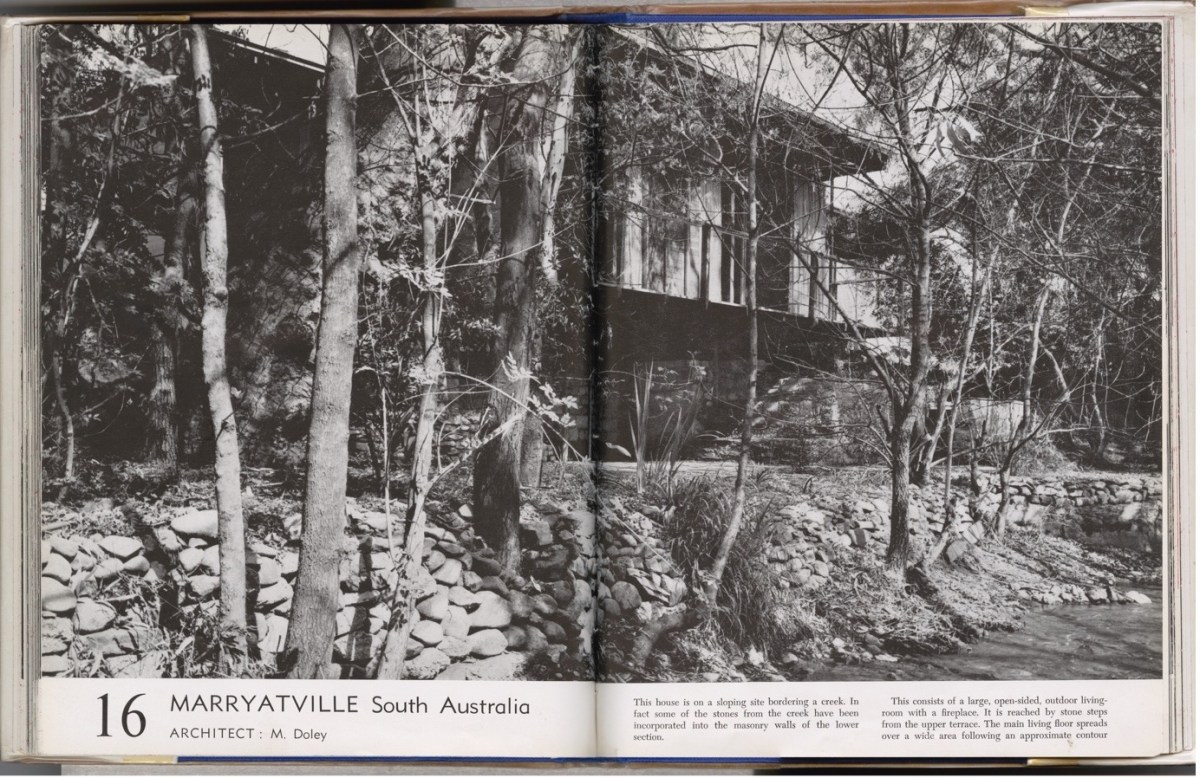

Chappel’s largely monochrome archive is brought to life with the contemporary videos, one of which explores the role of Adelaide’s early landscape designers at Doley House, Marryatville. Phillips/Pilkington Architects worked collaboratively with landscape consultant Viesturs Cielens to maintain the design spirit of this 1966 Institute of Architects Award winner when it was upgraded in 1998.

Doley House at Marryatville is another Adelaide modernist design to integrate the terrain and topography of a local creek into the garden design. Source: State Library of South Australia

Lust for Lifestyle’s exhibition audio provides a suitably mid-century soundscape, while family photographs and newspaper and magazine extracts highlight the role played by the print media in generating an appetite for these new and innovative designs.

Chappel’s articles also played an important role in promoting architects over building designers and contractors – a distinction that could be revisited as Adelaide becomes increasingly dissatisfied with its 21st-century proliferation of lowest-common-denominator new buildings.

Lust for lifestyle: Modern Adelaide Homes 1950-1965 is on until Sunday, July 24, at the State Library Gallery, Spence Wing (Ground floor).