Analytic FC Head of Content Alex Stewart looks at the impact being capped has on player valuations and earning capacity, and asks what that means for players who can choose to represent a number of different nations

Footballers have comparatively short careers, limited by age and, in some instances, even further by injury, bad advice, bad decisions, or bad luck. It is therefore natural that players should look to maximise their income and, intuitively, it seems like international recognition should be a way to advance their career and earning capacity. But to what extent does this hold true, and what does it mean for a player’s decision-making process?

Firstly, it should be fairly obvious that winning international caps increases a player’s desirability. There are several reasons for this: firstly, they have been judged as being among the elite of the pool of players eligible for whichever nation they might represent; secondly, international appearances put players on a bigger, more observed stage (although there are good data to suggest that buying players after strong performances in international tournaments is, at best, a lottery and, at worst, plain stupid); and lastly, caps bring cachet and potentially endorsements, commercial profile, and so on, which can bring benefit to the player’s club as well.

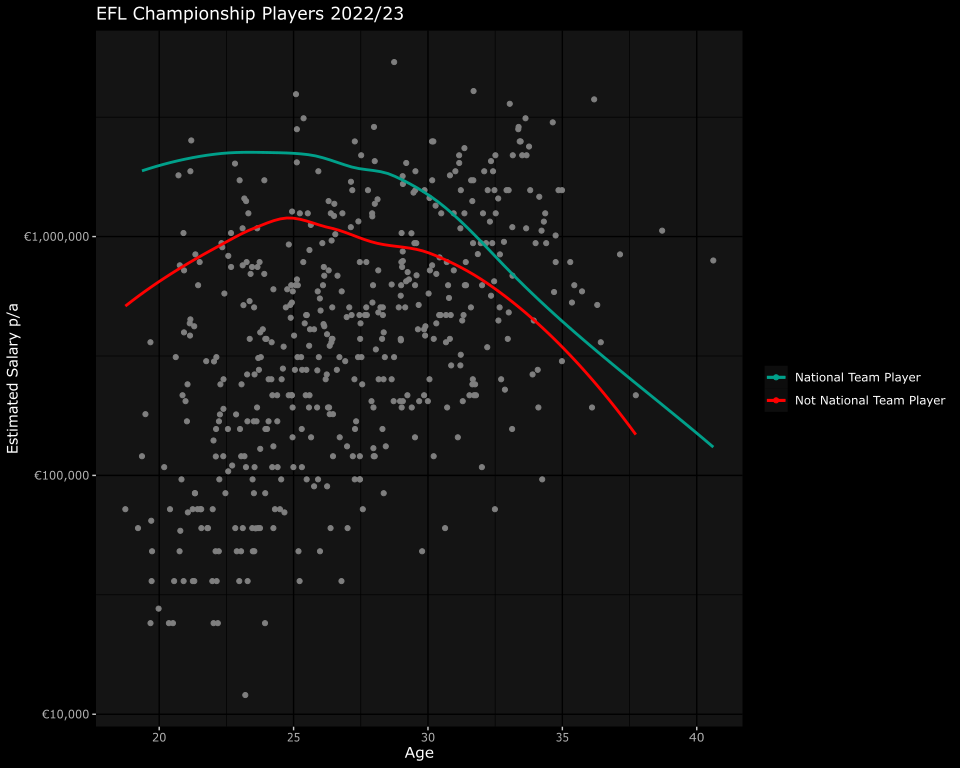

But what do the data say about salary? We looked at players in the men’s EFL Championship in 2022/23 and found some pronounced differences. The median salary increase for being a national team player in the Championship is €269K gross p/a. In younger age groups, this difference is even more pronounced (for example, in the 21-23 age group one would make three times more money as a national team player in the Championship), but the difference of roughly two times seems to hold in the later stages of players’ careers as well.

Assuming an average career from 20 to 33 years in the Championship, extrapolating the total career earnings in 2022/23 money brings €3.4M, while being a national team player from the start would increase this value to €6.7M.

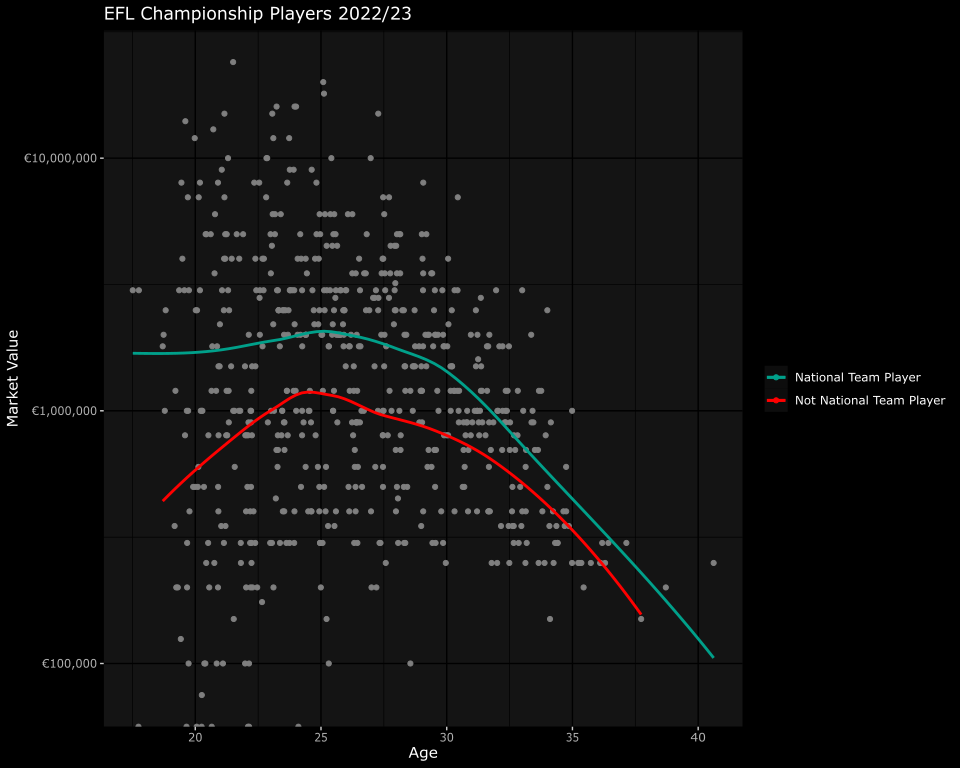

As one might expect, valuations also reflect this trend. On average, being a national team player (including youth national teams) in the Championship is reflected in a median difference in market value of €800K.

Again, in younger age groups, this difference is even more pronounced, with national team players in the 21-23 age group of 177% more expensive than their colleagues who do not play in a national team. In the 20 and under category, the difference amounts to 415%.

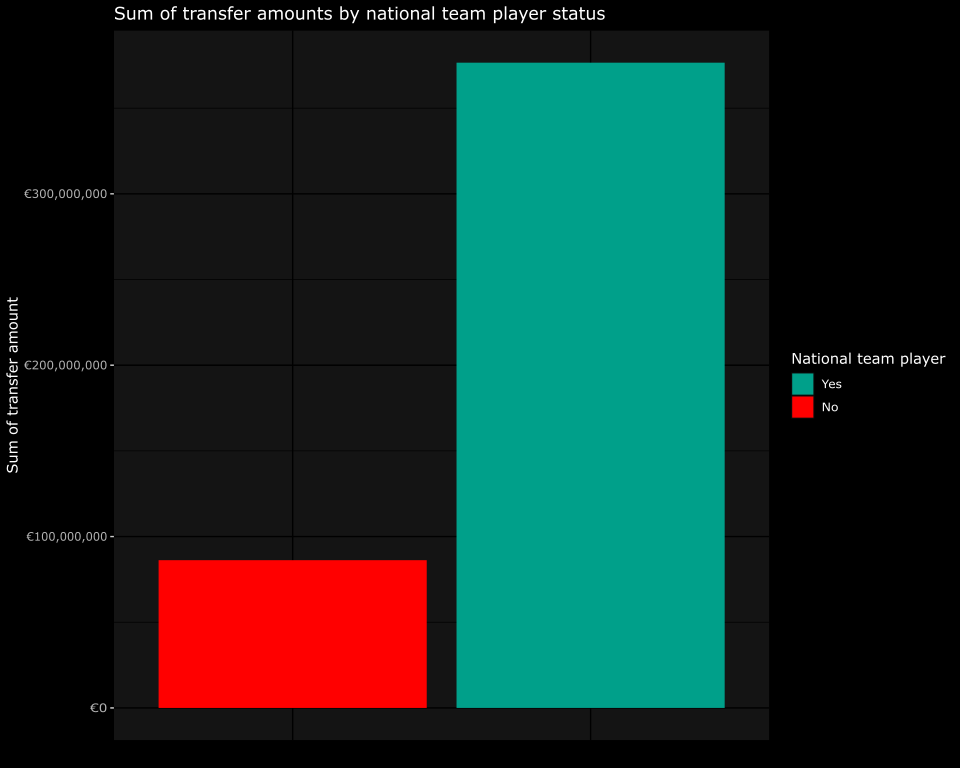

Analysing data for the last three years, the average cumulative transfer amount for international players were more than two times bigger than those transferring without having played for a national team, an average of €1.5M versus €720K. The cumulative fees paid for national team players in the Championship is almost 4.5 times higher.

So far, so obvious, you might say. To a degree, better players getting recognised with caps, and commanding higher fees and bigger wages, is slightly chicken and egg, although our research clearly shows that being capped allows a player to command bigger wages when it comes to negotiating their next contract after having been capped.

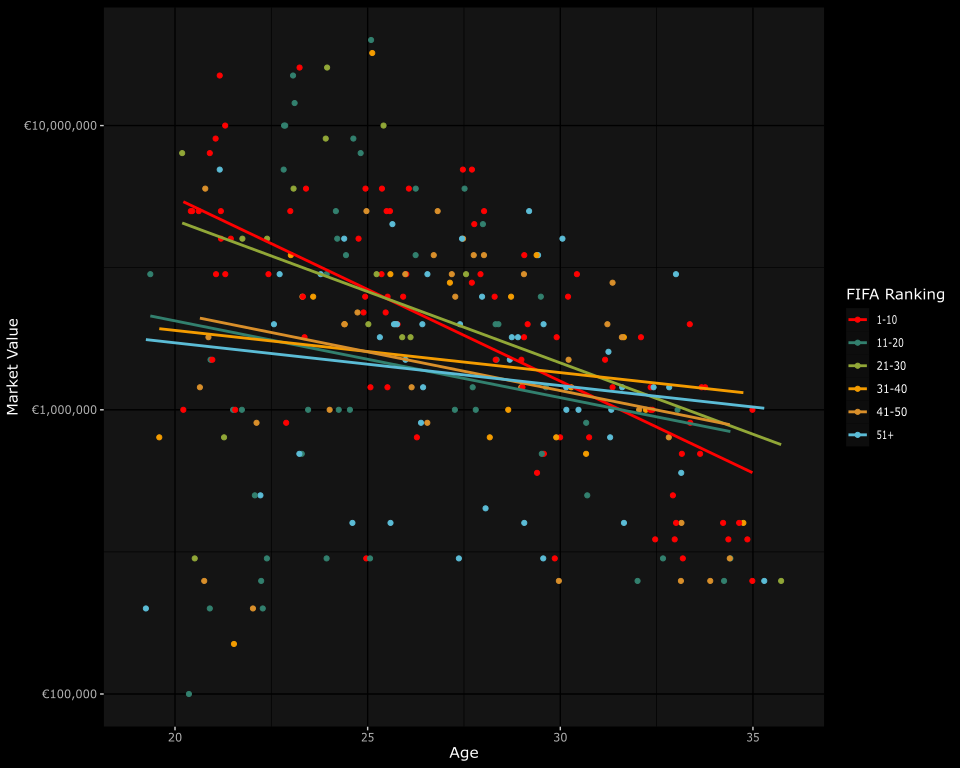

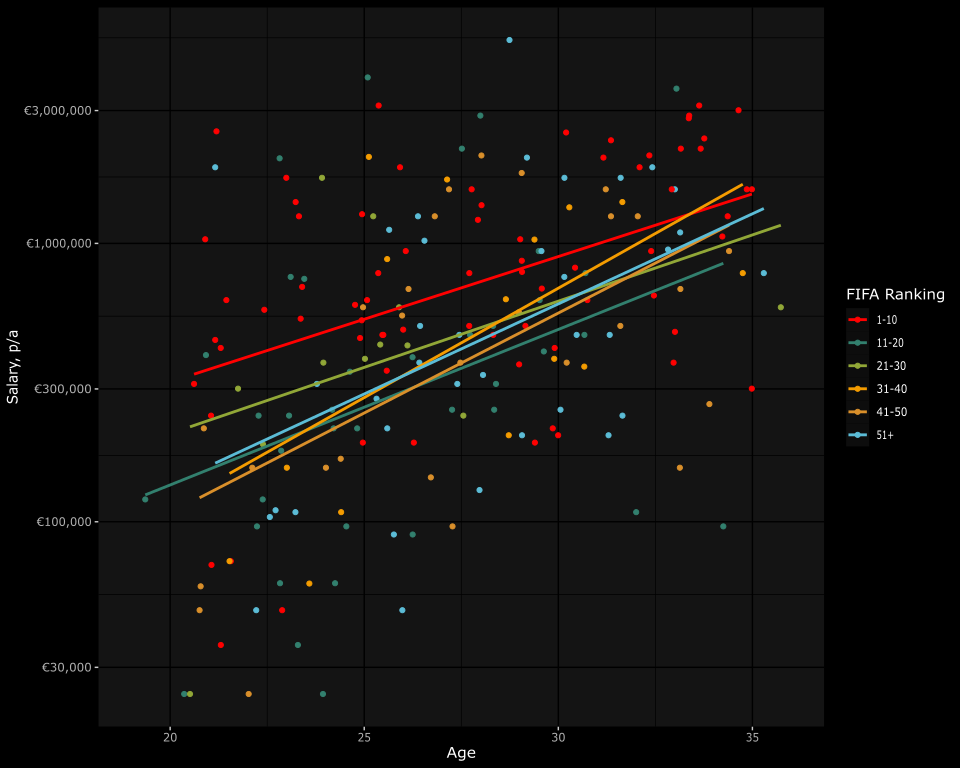

Of perhaps greater interest is to what degree the quality of the international team being represented affects matters. We will come to why that is important shortly, but firstly, the data: in short, while higher ranked nations’ players are valued more and the valuations decline relatively as the ranking does, there is far less relative impact on salary. Let’s take valuations first.

Again, examining the EFL Championship, we can see that the FIFA Ranking bracket from 1-10 reflects the biggest impact in market values for players between 20 and 25, primarily driven by former England U21 players. The median difference in market value in this bracket for top national teams can be around two times more.

Interestingly, there is also a significant presence of lower-value players in the age group of 32+ in the Championship, which might suggest experience playing for the youth English national teams could correlate to longevity in the English football.

Surprisingly, FIFA Ranking bracket 21-30 is the second most affected by national team valuation increase. This is primarily driven by national team players from countries like Chile, Morocco, Tunisia, and Poland. The 11-20 bracket looks somewhat undervalued, possibly because of the big presence of Welsh national team players in that bracket. However, from 31st place in the FIFA Rankings the analysis found no significant difference in market value.

For salary, however, the picture is different. Unlike with player valuation, FIFA Ranking has no material impact on salary (higher average salary values here more likely reflect the reality that better players play for better countries). It is also worth noting that English national team players consistently earn more than players playing in other national teams, which inflates the 1-10 bracket. But, in short, playing in a national team is a much more important factor for a player’s expected salary than the level of the team.

(It’s also worth saying that obviously, this scales for league prestige too – the better quality the league, the higher the wages, but within leagues, this ranking effect holds true).

This is interesting, because it suggests that it is in players’ interests, if not clubs, to select the most available international option to them (although the higher, the better, obviously). This is relevant because FIFA’s eligibility rules have generally trended towards making changing easier (with the exception of residency-alone-based qualification), and international federations have become far more astute when it comes to researching and then making overtures to players who can represent them. French-born players are a fine example of the combined effects of increased immigration and awareness among federations of diaspora players: in 2018, 19 of the 23 players in the French squad were eligible to play for another country, while around 30 players in other squads were born in France (with more than 10 having represented France at youth level). Morocco has been especially astute at leveraging its diaspora populations in France and the Netherlands, and many other nations are actively scouting players who could qualify for them due to grandparents, for example.

Obviously, there are many reasons why a player should choose one nation over another, complex reasons involving identity, a sense of belonging and pride, familial relationships and so on. Money isn’t everything and nor should it be when considering such matters.

But, from a purely financial perspective, what our research suggests is that a player could benefit almost as much financially from choosing to represent a lower-ranked nation than holding out for a higher-ranked one. This is especially acute for younger players, where making such a decision early in their careers could see significant accrued benefits over the course of their playing life.

Of course, as we have said, there is more to making such a decision than simply money, but if one were simply considering whether international players earn more the answer is an emphatic yes, and broadly irrespective of whose shirt they choose to wear.

Header image copyright IMAGO / Propaganda Photo / David Rawcliffe