For nearly a century, the conservative movement has fought for Wall Street’s God-given right to allocate capital as it sees fit.

The New Deal state’s affronts to private industry’s autonomy brought modern conservatism into being. Crusades against “big government” at home and communism abroad brought it into power. A reverence for investors’ discretion, and loathing of political challenges to it, is written into the movement’s holy texts, if not its proverbial DNA.

But this orthodoxy’s age is starting to show.

When conservatives first developed their veneration for free enterprise, the capitalist class was almost uniformly white and male, and predominantly socially conservative. Meanwhile, consumer-facing brands targeted a morally traditional mass public, and long-term investors saw no reason to spurn the American right’s favorite industries.

Economic modernity isn’t what it used to be. Today, some of America’s largest investors are pension funds that aggregate the savings of unions and public-sector employees, and mutual funds that pool the retirement accounts of white-collar professionals. None of these constituencies are remotely as demographically or ideologically similar to the contemporary conservative base as the capitalist class of yore was to the right-wingers of the mid-20th century. Indeed, over the past 70 years, America’s top executives, money managers, and professionals have grown more diverse, cosmopolitan, and socially liberal, even as the GOP base has grown increasingly animated by exclusionary nationalism and culture wars.

At the same time, consumer-facing brands now covet the favor of young city dwellers, both within America’s borders and beyond them. This is because such consumers are more likely to try new products than your average elderly person in rural America, and the former’s brand loyalty is more valuable, since they are less likely to die soon. That reality, combined with the imperative to compete outside the U.S. market, leads many of America’s most visible firms to align themselves, however superficially, with a progressive and cosmopolitan cultural politics.

Finally, the reality of climate change has given private investors both ideological and financial reasons to disfavor the carbon-intensive industries that supply a disproportionate share of the GOP’s corporate funding. Many public employees and socially liberal professionals like the idea of investing in the green transition, while plenty of far-sighted financiers believe that heavy exposure to fossil fuel assets is unwise in the long-term.

The marriage between conservatives and corporate America has, therefore, grown increasingly rocky. Cultural reactionaries have grown ever more incensed at the supposed treachery of their plutocratic coalition partners: For decades, social conservatives have fought to elect politicians who would protect private industry’s profit margins and control of production, only to see such corporations turn cop bashers into icons, demonize firearm manufacturers, institutionalize “woke” diversity trainings, and defund lawmakers who dare to challenge mainstream narratives about the 2020 “election.” Meanwhile, coal magnates have become similarly aggrieved, as capital flees their declining industry.

The Republican Party wants to give voice to these grievances. But for now, its leadership remains financially dependent on big capital’s patronage, and ideologically attached to the cult of free markets. Therefore, Republicans have come to believe — and/or pretend — that their discontents with corporate America derive from a conspiracy to subvert free enterprise, rather than from free enterprise itself.

Hence the GOP’s war on “woke Wall Street,” which is to say, its crusade against “environmental, social, and governance” investing, or ESG.

In recent years, money managers have begun giving greater consideration to firms’ environmental impacts, social responsibility, and internal governance when allocating capital. Companies that provide data showing that they meet certain thresholds for environmental sustainability can secure the designation of being an ESG investment. Asset managers then create environmentally friendly funds by pooling shares in ESG firms, and offer them to investors who want to “do well by doing good,” or else who simply wish to balance out any climate risks in their portfolios by gaining greater exposure to companies that stand to benefit from decarbonization.

The market for “sustainable” financial products is vast. As of 2020, $17.1 trillion of U.S. assets were allocated to “sustainable investing strategies,” while more than 800 registered investment companies boasted ESG assets. That same year, the asset-managing behemoth BlackRock announced that it would start offering “sustainable versions” of its flagship portfolios, use “ESG-optimized index exposures in place of traditional market cap-weighted index exposures,” drop coal producers from its active investment portfolio, and use shareholder resolutions to pressure companies into greater environmental responsibility.

ESG in general, and BlackRock in particular, are therefore natural punching bags for a Republican Party with populist pretensions. Last Thursday, Florida announced that it was removing $2 billion worth of assets from BlackRock’s management in protest of the company’s ESG policies, which allegedly put politics above returns. Louisiana and Missouri had previously divested from BlackRock in October on similar grounds.

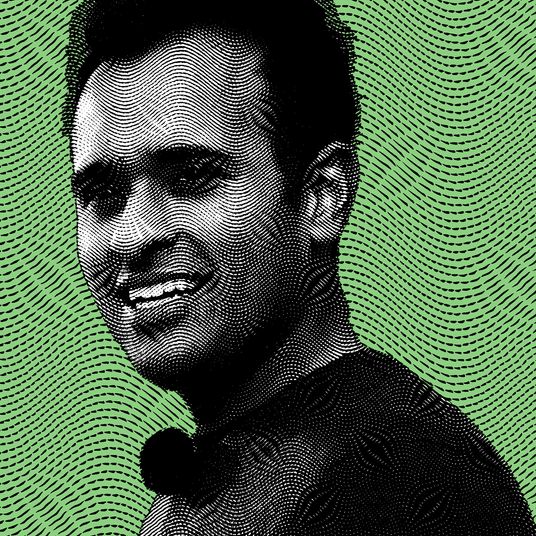

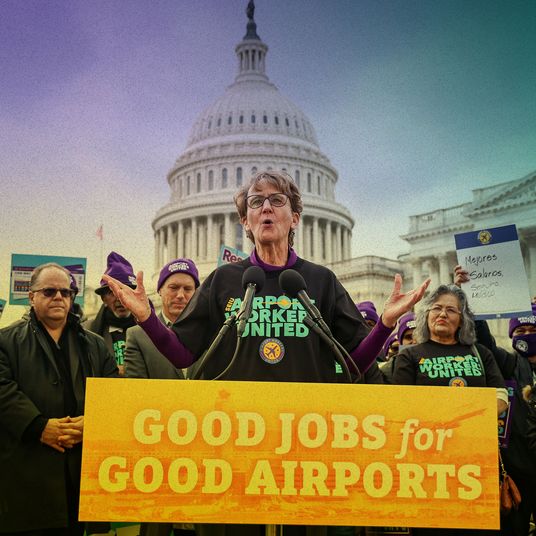

On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, House Republicans are preparing to use their newfound oversight and investigatory authorities next year to, in the words of Kentucky representative Andy Barr, “stop this nonsense of politicizing capital allocation through ESG.”

Barr and his fellow conservatives see ESG as “the weaponization of financial regulation designed to discriminate against American energy companies” and blame it for rising energy prices in the United States.

“We want these mutual fund companies, ETF companies, the members of the [Investment Company Institute trade group] to come before Congress and tell us how they’re going to change course and start prioritizing investor returns again, instead of promoting this fraud of ESG,” Barr told Politico in November.

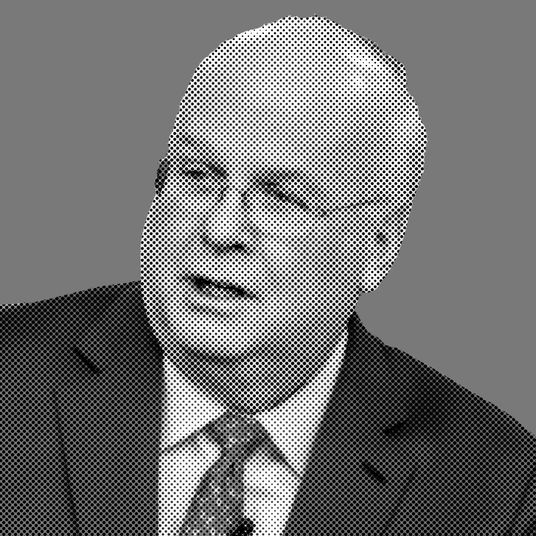

Outgoing GOP senator Pat Toomey echoed Barr’s sentiments, encouraging his colleagues to crack down on far-left finance. “Many liberal politicians are pressuring banks to use both their balance sheets and their influence to address issues wholly unrelated to banking, such as global warming, gun control, voter rights, and abortion,” Toomey said in a recent statement. “Several large banks have been far too willing to acquiesce to these demands by embracing a liberal ESG agenda that operates outside of representative democracy.”

In other words, Republicans claim that liberal activists and a small number of “woke” money managers are systematically betraying the will of investors, forcing corporations to perform socially liberal gestures and starving fossil-fuel companies of capital, thereby undemocratically subverting the conservative agenda and driving up energy costs for ordinary Americans.

There are several problems with this story.

First and foremost, it simply is not the case that a well-placed liberal cabal has imposed ESG on the broader capitalist class.

Ideology, not insight, has led Republicans to this conception of the ESG phenomenon. The notion that bleeding-heart corporate managers might prioritize social goals above the interests of their investors is a familiar threat in the conservative imaginary, and one that can be neutralized through ideologically congenial means. Milton Friedman first warned of the perils of socially conscious managers in 1970, when he articulated the “shareholder theory” of business ethics. In short, Friedman argued that in “a free enterprise, private property system, a corporate executive is the employee of the owners of the business” and therefore has a “responsibility to conduct the business in accordance with their desires” — and no one else’s. The solution to the problem of activist managers was, thus, to align management’s incentives with those of shareholders, while giving the latter more oversight of the firm’s affairs.

Confronted by the rise of ESG, Republicans instinctively seek to place the phenomenon into the Friedmanite frame. But it just doesn’t fit.

BlackRock is not rolling out “sustainable” portfolio options in defiance of investors’ desires, but in response to them. In a recent survey of 550 firms by Bloomberg, 62 percent of respondents said that they were incorporating ESG concerns into their business “at the behest of their clients.” A separate poll of large investors conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that 88 percent believed that “asset managers should be more proactive in developing ESG products.” This consensus reflects both the ideological inclinations of left-leaning investors such as blue-state pension funds and the financial imperative to insulate portfolios from climate risk.

It is true, as Senator Toomey suggests, that private investors set capital-allocation priorities “outside of representative democracy,” even though their decisions have implications for our collective life. But conservatives aren’t arguing that primary authority over investment should therefore lie in the hands of the democratic state. Rather, they’re insisting that investors’ decisions should be free from political interference … while trying to interfere in investors’ decisions.

The second flaw in the right’s narrative is that their story actually treats ESG’s proponents with too much credulity. The ESG movement has not actually had a large impact on fossil-fuel firms’ access to capital. This is partly because the system for classifying firms as “ESG” is easily gamed. A recent study from Columbia University and the London School of Economics compared the governance records of U.S. companies in 147 ESG funds with those of U.S. companies in 2,428 non-ESG funds. It found that firms in the ESG portfolios actually had worse labor and environmental records than those in ordinary portfolios.

For its part, BlackRock offers investors plenty of opportunities to profit off the climate’s degradation. For all its ESG advocacy, the asset manager had about $260 billion invested in fossil-fuel companies as of February 2022.

More fundamentally, though, divestment just isn’t a very effective form of activism. For any entity to divest from an asset, it must sell that asset to another buyer. When BlackRock sells off its coal holdings, someone else takes them on. Whatever ideological trends gain traction with America’s large investors, if a given business promises good returns, someone is going to invest it; global capital markets are very large. To the extent that U.S. coal firms are losing access to capital, it isn’t because of liberal activists but because of their own failures to compete on price with natural gas and renewables. Once again, the problem facing conservative champions of aggrieved interests is not the subversion of capitalism but capitalism itself.

Much the same can be said of the right’s complaints about energy prices. The GOP is not wrong that energy would be cheaper if America fully exploited its copious fossil-fuel endowments. But the primary impediment to fossil-fuel production in recent years has not been any shortage in the capital available to dirty energy firms or even federal restrictions on drilling. The obstacle has been fossil-fuel investors, who’ve forced oil producers to honor Milton Friedman’s doctrine and put shareholders first: Instead of recycling their profits into expanded production, fossil-fuel companies have prioritized paying out dividends to shareholders, many of whom suffered losses during the 2014 oil-price collapse and wished to be made whole.

Finally, as already noted, consumer-facing brands do not amplify liberal cultural sentiments because they care more about virtue signaling than profit-making; they do so because young city dwellers are both culturally liberal and a major profit center.

In sum, the right’s problem isn’t that large asset managers are betraying the desires of investors; it’s that investors and consumers in the modern economy do not desire what the right wants them to. That is not a problem that conservative orthodoxy can solve. So conservatives are focusing on an imaginary problem that is amenable to their movement’s timeless truths.