Windows Defender, the anti-malware software that's built in to Windows, is going to start removing utility software that tries to scare users into upgrading, starting in March.

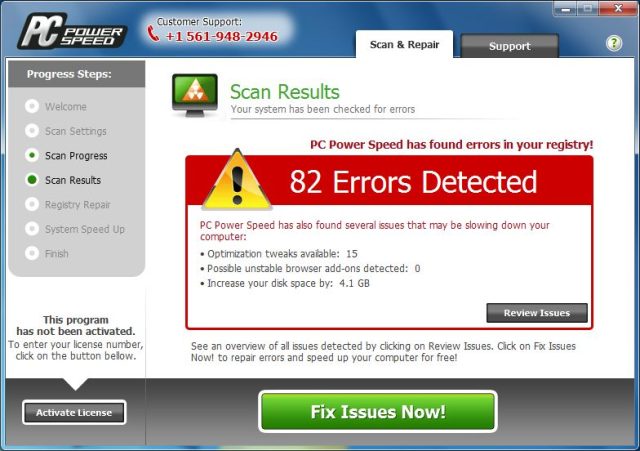

The Windows software ecosystem has a large variety of software of dubious merit that claims to detect and diagnose faults. These programs often offer a free version that purports to find problems and a paid version that can supposedly repair those problems. Frequently, the problems detected by this software are either nonexistent or misleadingly described, spuriously blamed for crashes or poor performance.

Under Microsoft's new policy, any software that the company deems to be coercive will be a candidate for removal. Coercive elements include software that's particularly alarming or exaggerates the risks, software that says the only way to repair the problem is to upgrade, and software that tells users they must act within a limited time. Direct payments will be penalized, but so too will apps that require people to take surveys or sign up for newsletters.

This is a welcome move, if a bit late. This kind of scaremongering crapware has been around for literally decades and has rarely had much legitimacy to it. Bad actors have instead preyed on the trust and lack of knowledge of Windows users, exploiting fears around security and stability to sell software that at best does nothing useful. At worst, these programs actually cause problems, deleting required registry entries or removing useful files. The decision to brand such programs as unwanted has been a long time coming.

Microsoft's first action against such software took place in 2016, when it started penalizing software that either misclassified files (for example, by deeming desirable system files as "junk" to be removed) or provided no meaningful information about the "errors" that it detected. Under the new policy, even software that should happen to accurately diagnose and describe genuine problems will be penalized if its upsell effort is too aggressive.

Listing image by Karl Herler

reader comments

148