It’s still early days for Instacart the company, and even more so for Instacart Advertising, its budding ads business.

It’s still early days for Instacart the company, and even more so for Instacart Advertising, its budding ads business.

But Instacart is at the forefront of a movement among data-driven companies over the past two years to launch ancillary ad platform businesses, including direct competitors like GoPuff, partner competitors like Kroger and unrelated product or payment companies.

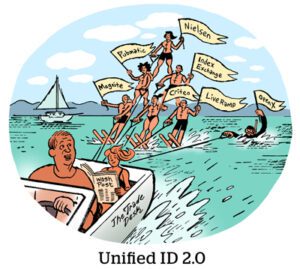

The sailing hasn’t always been smooth, though.

In 2019, Instacart kicked off its advertising ambitions with the addition of paid search options for brands in its online grocery service.

But that test-and-learn attitude was put on hold when the company was tossed into the deep end by the pandemic. Instacart launched a self-service ad platform in May 2020 to monetize a huge surge of first-time customers in quarantine.

The pandemic is finally abating, but the potential for ads on the platform is still ripe.

“Instacart presented the opportunity to work with a product engineering team and customers to build a brand-new ad business from the ground up,” said Instacart sales VP Ryan Mayward, who joined the company last March after a nine-year stint in ad sales at Amazon.

Call it a feedback loop or a flywheel, but Amazon is a clear example of how fast an ad business can grow when the ad tech is connected directly to purchases. Instacart is looking to capture some of that magic.

Why advertising?

Instacart needs a healthy ads business to make grocery delivery economics work.

Grocery is already a low-margin industry – and that’s when people go to a store and do their own shopping. Using Instacart adds the cost of shoppers and home delivery.

But, as opposed to when new customers use the app, Instacart doesn’t need to hire more employees when advertisers use its new self-serve platform, which means every additional ad dollar helps relieve the strain on grocery delivery to turn a profit (which it doesn’t).

Instacart has demonstrated its dedication to growing its ad business through several high-profile hires. The company poached Amazon Advertising head Seth Dallaire as CRO in 2019 and former Facebook ad industry leader Carolyn Everson was named president last year.

Everson and Dallaire both departed Instacart in 2021 – Everson over alleged misunderstandings about the scope of her role and Dallaire was poached (again) by Walmart, where he’s now CRO – but Instacart responded in turn.

In December, Instacart hired Stephen Howard-Sarin, former VP of strategy and transformation for Walmart Connect (Walmart’s ad business), to lead its retail media group.

Platform basics

It’s easy to sum up Instacart’s current ad offering. Brands can pay to list a featured product in search results, on the homepage or in personalized lists of suggested products on the post-checkout page.

The ads sell on a cost-per-click basis in a second-price auction. Instacart started with a first-price auction in 2019, Mayward said, but switched to second price because that’s how CPG marketers purchase programmatic retail media elsewhere.

Though its ad tools are basic right now, Instacart does have some nifty differentiators.

For one thing, Instacart sees sales across many grocers, which allows it to provide advertisers with a broad array of metrics, such as market share, household penetration and share of shopping baskets that carry their product, said Himanshu Jain, VP of product management at CommerceIQ, an Instacart Ads partner.

With those analytics, Instacart has established itself as a default for CPG brands to invest in ecommerce grocery and delivery, because it’s easier than enlisting retailer-specific platforms one by one, Jain said.

Although startups rarely compete with the likes of Amazon and Walmart for marketer mindshare, Instacart has cleared that hurdle at least.

Opportunity or illusion?

But Instacart’s advertising capabilities still need to catch up to the possibilities.

Though, to be fair, Amazon, now a behemoth, also started slow and simple with just sponsored product search results.

Instacart is “laser-focused” on core CPG brands, Mayward said. Instacart added CVS in 2020 and Walgreens last year, which helped attract non-food advertisers like L’Oréal, he said. But, at this point, Instacart isn’t making an active push for non-endemic brands, the way a clothing company for kids might use the Amazon DSP to target people who buy baby food.

The big retail media players such as Amazon, Walmart, Target and Kroger all have audience networks that target customers across the web or on social media. Instacart can’t add non-endemic advertisers because it sells only owned-and-operated media.

“It’s a fascinating area to discuss, but no plans to share,” Mayward said.

Instacart also has no video units. Mayward said video will be a priority for testing this year as a way for brands to present themselves using richer media.

In 2020, Amazon started testing sponsored videos in some search results, often for well-known brands trying to distinguish themselves from cheaper knockoffs.

On the affiliate program front, well, Instacart doesn’t have one. Recipe publishers or influencers who could drive CPG sales have no way to monetize the traffic to Instacart.

Instacart could also partner with other major platforms to monetize its data, though. Kroger, for instance, signed a deal with Roku in 2020 to attribute CTV campaigns based on store sales.

Although there’s a lot that Instacart doesn’t have in place yet, it’s been able to knock together a meaningful ad business already. The company earned $300 million in ad revenue in 2020 and has a goal to reach $1 billion in 2022, a source told The Wall Street Journal last year.

Big vs. small

One of the most important questions for Instacart Advertising is whether it will be a more valuable product for big CPG brands or newer ecommerce companies, smaller regional brands or third-party sellers.

As always, there are huge advantages to being, well … huge.

Campbell Soup Company was a big direct brand customer that joined Instacart Advertising in 2020. As a brand with hundreds of millions of dollars in retail media commitments, it gets the first crack at new Instacart ad products, like test driving an offer for free samples during the holidays.

Meanwhile, when Noops, a plant-based pudding company, started reaching a national distribution footprint last year, it made sense to start advertising on Instacart, CEO and founder Gregory Struck told AdExchanger.

“Oftentimes, being on the platform just isn’t enough,” Struck said. Noops has to be careful to turn an ROI on its ad investments when it’s trying to compete with Kraft-Heinz’s JELL-O brand, a 400-pound gorilla in the pudding category with so much more to spend.

But there are pros and cons for every brand.

Mayward said that challenger brands or specialty products like vegan, gluten-free and keto have very strong use cases because they can buy targeted keywords.

Challenger brands also benefit because customers browsing ecommerce grocery options are “confronted with a new selection” and willing to try new products, he said. A smaller brand can elevate itself on Instacart more easily than it can buy or earn shelf space in stores.

Driscoll’s, for example, the leading berry brand, is a direct advertiser on Instacart, but must develop new ways to stand out in ecommerce, and on Instacart in particular, VP of brand and product marketing Frances Dillard told AdExchanger last year.

Driscoll’s has invested tens or hundreds of millions into breeding the plumpest blueberries and reddest strawberries that stand out in store aisles. That ROI doesn’t transfer to a JPEG of Driscoll’s berries next to a JPEG of some other berries.

Another consideration for advertisers is the fact that Instacart’s most compelling analytics, like granular data on in-category market share or household penetration, are dished out based on the percent of overall sales allocated to advertising, said CommerceIQ’s Jain.

In other words, smaller brands aren’t boxed out of the best data by minimum advertising thresholds – it’s about what percent of their sales are reinvested into ads.

The competition conundrums

Aside from attracting Fortune 500 type brands and the long tail of regional and SMB companies, Instacart must also navigate tricky relationships with its retail co-opetition.

Walmart and Target are investing in their own ecommerce grocery and delivery services. Both still partner with Instacart, but at some point may in-house those sales rather than sacrifice a cut to a middleman vendor, just as has happened with Walmart and Target’s respective ad platform businesses, said Forrester principal analyst Sucharita Kodali.

The next tier of grocery chains, like Kroger and Albertsons, have grocery delivery and ad platforms that compete with Instacart too.

“If Instacart gets too greedy or cannibalistic, grocery chains could delist and the pendulum could swing back to the grocers’ own sites or apps,” she said.

It’s a difficult question for Instacart, because creating valuable products for advertisers will invariably create tension with retailers.

When Campbell’s tested Instacart’s free sample ad product in November and December, it didn’t just offer samples to people who regularly purchase soups or broth or who hadn’t bought soup recently. Instacart targeted shoppers that previously purchased another company’s broth, and offered them the Campbell’s freebie before they added their regular product to the cart.

Some retailers and rival brands may see that happen with loyal customers and say: “Hey, Instacart, what the frozen foods is this about?”

But Instacart can offer a major selling point to big brands as a window across the grocery category.

“The biggest differentiator for Instacart compared to a Kroger or even Amazon is that we can look across retailers and potentially use it to learn how loyal people are to a certain retailer,” said Trace Rutland, digital hub director for the Ocean Spray brand.

For example, are people who buy Ocean Spray in Kroger stores and via the Kroger ecommerce platform susceptible to another brand’s advances on Instacart, or vice versa?

Ocean Spray wants that data transparency from Instacart – and is willing to pay for it.

Although grocery chains will likely feel differently about Instacart potentially channeling shoppers to different stores when multiple grocers carry the same product – or if Instacart starts targeting the purchase habits of loyal customers.