When some 8,500 ranchers, stockers, feeders, and meat-packers began arriving at the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center, in San Antonio, for the annual National Cattlemen’s Beef Association conference and trade show this past February, they had reason to celebrate. Per capita U.S. beef consumption had grown for four years straight. Many consumers were buying more expensive grades of meat, while chefs were transforming humbler portions—the sirloin culotte, the bavette, the brisket—into signature dishes in some of the country’s most renowned kitchens. And thanks to new tariff-lowering trade pacts with Japan and the EU, the U.S. beef industry was poised for international expansion. “Demand is unlimited,” declared Bill Fielding, CEO of Flatonia-based HeartBrand Beef, as I stood savoring a tiny toothpick portion of his company’s decadent Wagyu ribeye.

And yet a sense of unease hung over the convention. Over the previous year, long-running concerns over beef’s impact on the environment and human health had gathered new strength. Blue-ribbon scientific panels affiliated with the United Nations and the Lancet medical journal warned that global red meat production was an outsized contributor to climate change and advocated that diners reduce their consumption. Buzzy documentaries such as Netflix’s The Game Changers—coproduced by action-movie mainstays Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jackie Chan, and James Cameron—extolled the benefits of going vegan. Politicians had seized on the issue too, with a Green New Deal fact sheet highlighting the problem of “farting cows” and Republicans firing back that Democrats were scheming to “take away your hamburgers” or, in the words of U.S. senator Ted Cruz, “kill all the cows.”

Even some who owe their livelihoods to beef have argued against the way much of the industry works. In the 2019 cookbook Franklin Steak the renowned Austin barbecue chef Aaron Franklin and his co-author Jordan Mackay wrote that the current beef supply chain “does not produce much good meat and is also negative in terms of animal welfare, public health, and the global environment.”

And then there’s the threat posed by fake meat. Two California-based start-ups, Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, have publicly declared war on animal agriculture—“a prehistoric and destructive technology,” in the words of Impossible’s mission statement. Sales of plant-based meat products have surged, and the products have appeared everywhere from Burger King (home of the Impossible Whopper) to Costco (eight-patty packs of raw Beyond Burgers). Giant food conglomerates such as Kellogg’s and Nestle are rolling out their own entries, and the Swiss investment bank UBS has projected that global sales in the category will grow almost twenty-fold in the next decade. It’s not that veganism is rampantly on the rise but simply that consumers are eating a wider variety of proteins. A recent Yale survey on climate change and the American diet found that although just one percent of Americans said they were vegan, more than half were willing to eat more plant-based meat and less beef.

At the NCBA conference, the marquee session is typically a state-of-the-industry address by the data and research firm CattleFax. This year, CattleFax’s CEO, Randy Blach, took the stage to preach the good news in front of a replica of Gruene Hall’s iconic white clapboard facade. But toward the end of his speech, he sounded a darker note.

“I see a lot of you in the room that didn’t live through what we went through from 1980 to 1998,” he said, referring to the industry’s decades-long slump after nutritionists and the U.S. Senate fingered beef in the late seventies as a major culprit in the rising incidence of heart disease and cancer and recommended a dietary shift to poultry and fish (see “What’s Harvard’s Beef With Texas A&M?”). A PowerPoint slide on a screen above Blach showed a plummeting trend line. “Look at these numbers,” he said. “Beef demand was cut in half. Cattle inventory went down twenty million head.”

Now Blach pivoted to the present. “I challenge you that if we don’t handle this sustainability message, this is what we could be dealing with again,” he said. “I believe this is our greatest risk as an industry.” Blach encouraged beef producers to fight back. “We’re always on the defensive,” he said. “We’ve got to take the offensive.”

The industry, seeking to avoid the fate of milk—whose sales shrank 10 percent from 2017 to 2019 alone, while sales of plant-based milks such as soy, oat, and almond grew 14 percent in the same period—had already backed the REAL Meat Act in Congress, which sought to keep plant-based burgers from being sold alongside actual animal protein in the grocery-store meat case. NCBA lobbyists gave conference attendees wallet-size cards with talking points “correcting cattle’s climate record.” The cards cited the efficiencies of the U.S. beef cattle industry and the widely agreed-upon fact that it has reduced its methane emissions by 30 percent since the mid-seventies, just before onset of the so-called “war on fat.” But beef’s critics aren’t going away because of a few talking points, particularly after the coronavirus pandemic decimated poultry, pork, and beef packing plants, infecting nearly 40,000 industry workers and killing 180 as of early August.

In the months after the NCBA conference, I wanted to see how beef producers at every level—from boutique ranchers and butchers to sprawling feedlot and slaughterhouse operators—were responding to the climate threat, the COVID-19 threat, and the threat that plant-based meats and consumer concerns pose to their bottom lines. Many sectors of the beef industry disagree vehemently with one another, sometimes to the point of wishing for the other’s demise. But I found them all in a mad dash to out-innovate, out-price, and just plain out-argue the forces that would replace them. They share a broad goal: to ensure that beef remains at the center of the dinner table.

Back to the Land

“Look at that animal wallowing over there,” said Taylor Collins, a trim and exuberant 37-year-old entrepreneur and rancher, as we sat in a Kawasaki Mule in one of his back fields. A bison calf—a couple-hundred-pound ball of shaggy brown fur—dropped to the ground and started rolling in the grass like a Labrador playing in a suburban backyard.

One hundred bison surrounded us. Most had their heads bowed as they grazed through the pasture. Two bulls—one, Collins said, had genetics tracing back to the herd that famed ranching pioneer Charles Goodnight kept along with his cattle—stood back, eyeing us warily. Another calf pranced over to the Mule and started nuzzling its head against the corner of the bed. Anyone would have been tempted to pet it.

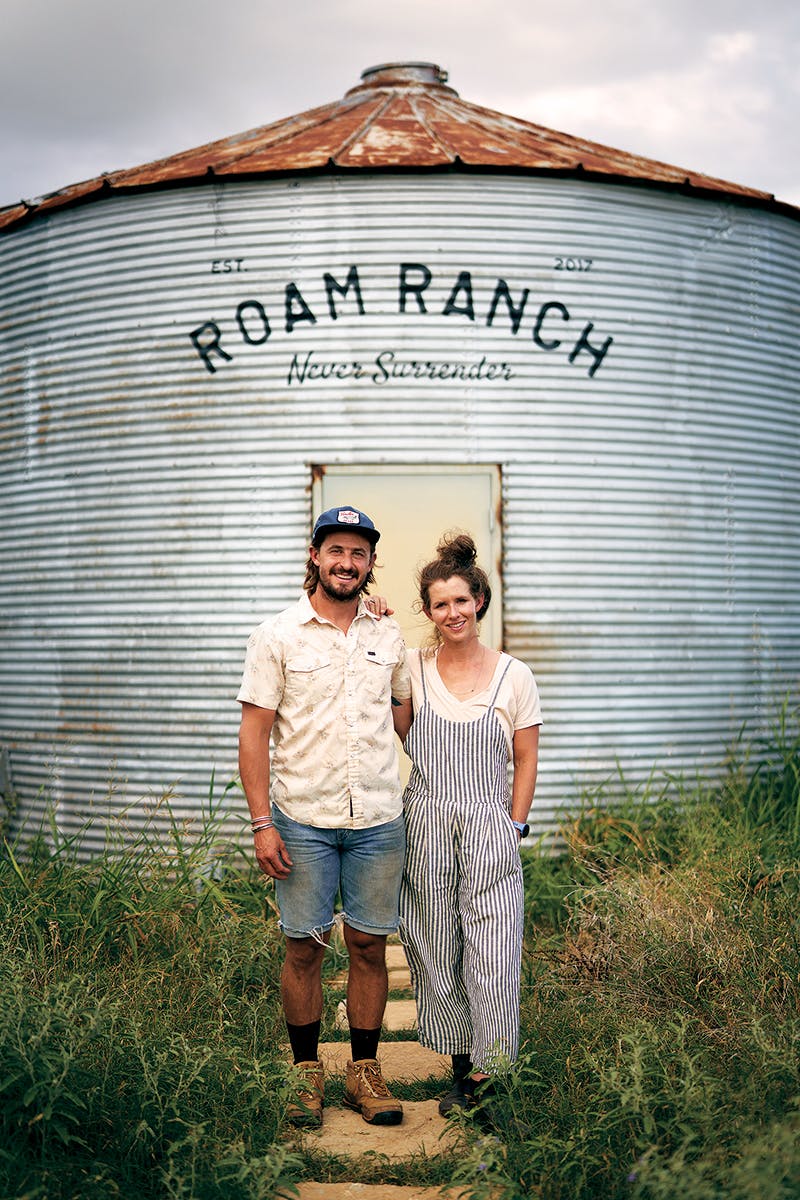

Collins and I were touring Roam Ranch, the thousand-acre Hill Country property where he and his wife and business partner, Katie Forrest, raise bison, pigs, turkeys, chickens, and honeybees. Just setting foot onto the place evokes the romantic ideal of Texas ranching. The gently rolling, oak-studded land hugs the Pedernales River just a few miles outside Fredericksburg, and the animals graze on native forage, just as they did generations ago. (Collins and Forrest are committed enough to the pastoral ideal that they’ve chosen to raise bison, which were in Texas long before Spanish settlers brought cattle north from Mexico.) But Roam Ranch isn’t only a throwback. Collins and Forrest have conceived it as a kind of demonstration project to show that eating red meat and saving the planet can be compatible goals.

It’s a notion that flies in the face of a lot of established wisdom. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization has concluded that livestock production is responsible for 14.5 percent of all human-caused greenhouse-gas emissions, and beef is that sector’s top contributor, responsible for a little less than half of animal agriculture’s total footprint. Research has shown that cattle take up a disproportionate amount of land (leading to deforestation, particularly in the developing world), belch too much heat-trapping methane (which is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide), and eat too much food for the amount of meat they give us (cattle need four times as much feed as chickens to gain a pound). Their food, meanwhile, is often grown in resource-intensive ways, requiring huge quantities of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. And waste from the feedlots where the vast majority of U.S. beef cattle spend their final months can be an air- and water-pollution nightmare.

Collins and Forrest concede most of these points, but they think climate scientists and vegan activists have arrived at the wrong conclusions. (They are former raw-food vegans themselves.) Instead of junking beef entirely, they believe we should strive to eat “better beef,” which must come from cattle raised in a radically different way. This starts with grazing ruminant livestock—cattle, bison, and their cousins—from birth to death entirely on grass and eschewing chemical fertilizers, growth hormones, and antibiotics. But the new approach goes much further. Collins and Forrest think that cattle and bison should take up more land, not less, so long as we use them to remake our entire agricultural system—revitalizing degraded soils, restoring grasslands, eliminating monoculture row crops, and, in the process, helping to trap more carbon and mitigate climate change. The strategies to arrive at these goals come from a simple premise: that a good farm should mimic nature.

At Roam Ranch, bison are treated more like wild animals than like typical livestock. Cows aren’t artificially inseminated (standard practice in the beef industry, where prize bulls continue to father offspring decades after their deaths); male calves aren’t castrated; no calves are weaned (“there are still some year-and-a-half-year-olds trying to milk,” Forrest told me). But Collins and Forrest’s biggest emphasis is on how the bison graze. In the wild, ruminant animals face predators, and that constant threat helps drive them to gather in herds that stay on the move and avoid the overgrazing that depletes soils and causes erosion. Collins and Forrest initially thought about emulating this part of nature by installing high fences around Roam Ranch and controlling their herd’s grazing patterns with a pack of wolves. (“Then we thought, ‘What if all the wolves get out?’ ” Collins said.) Instead, Forrest and Collins use a portable electrified fence to move their herd around, sometimes several times a day.

This system creates a virtuous cycle. As the bison move through the fields in compact herds, they leave behind their manure, which fertilizes the soil and attracts dung beetles and earthworms, which spread the stuff around and amplify its impact. Then birds swoop in to eat the insects and chewed-up seeds, other birds swoop in to eat those birds, and soon an entire robust ecosystem begins to come alive. As underground microbial life increases, so does the amount of carbon stored in the soil—which enhances its ability to retain water.

Collins and Forrest didn’t dream up these ideas on their own. Serial entrepreneurs, they spent their pre-ranching careers launching grocery-store food products with a healthy hook and scored a major hit with Epic Provisions, a meat-based protein bar company, which they sold to General Mills in 2016 for a reported $100 million. During their Epic years, while trying to reconcile meat eating with their environmentalism, they came across the work of a Zimbabwean ecologist named Allan Savory who popularized the idea that ruminants, if grazed in high densities and moved frequently, could restore overgrazed lands and begin to reverse climate change. Many soil scientists think Savory’s claims are exaggerated (in a controversial TED Talk, he argued that applying his technique to degraded grasslands worldwide could reduce atmospheric greenhouse gases “to preindustrial levels”), but his core idea has become a central tenet of a growing global movement called regenerative agriculture.

A peer-reviewed 2018 study by Michigan State scientists found that an Upper Midwest ranch using Savory-like “adaptive multi-paddock grazing” was able to sequester 3.59 metric tons of carbon per hectare, which more than offset the emissions of the ranch’s grass-fed cattle during their finishing stage. In other words, the ranch—methane-spewing cattle and all—was a carbon sink. Another study of White Oak Pastures, a farm in Georgia, found similar results. General Mills, responding in part to prodding from Forrest and Collins, has said it will “advance regenerative agriculture” on one million acres of farmland by 2030, and Whole Foods anointed regenerative agriculture its number one food trend of 2020. Lew Moorman, one of the founders of Soilworks, a San Antonio–based start-up that is investing in regenerative farms, told me that regeneratively raised beef was “one of the few win-win-win things I’ve ever come across.”

Last year, Collins and Forrest and some of their former Epic employees started a new venture, Force of Nature Meats, which sells packaged beef, bison, elk, venison, pork, and wild boar from similarly minded producers in Texas and beyond—including White Oak and Roam. It’s not cheap. Force of Nature ground beef costs $8.99 per pound, nearly twice as much as the national average for conventional ground beef. But Collins and Forrest envision a future where regeneratively raised meat is widely available and price comes down with scale.

“My dream would be to turn all of our semi-arid crop production land into grazing land again,” Forrest told me. “Like, exactly what it was supposed to be, which is grasslands.” That would mean a reduction of much of the corn production in the United States (a third of which is currently used for animal feed) and likely an increase in the population of ruminants that could actually digest the grasses on all of that reclaimed pastureland.

Regenerative agriculture isn’t settled science. While it’s clear that good grazing practices and other regenerative techniques can boost soil health, reduce erosion, and increase water retention, it’s unclear exactly how much carbon the soil sequesters and for how long. Regional variability also hasn’t been fully studied, and the research showing net-carbon-negative beef was conducted in relatively lush climates. Jason Rowntree, a Kingwood-raised, Texas A&M–educated professor at Michigan State who has led much of that work, told me that it would be “considerably more challenging” to get the same results in more arid climates. But even with the uncertainties, Forrest and Collins are certain the system is far better than what’s currently in place.

“When we went vegan, one of the big driving factors was seeing feedlots,” Collins said. “You just know there’s something wrong when cows are standing in two to three feet of shit. It doesn’t take an enlightened individual to know that there’s something wrong with this.”

Forrest nodded in agreement. She had another dream: “to get rid of feedlots,” she said. “Like, altogether eliminate feedlots.”

Maximum Production, Lowest Cost

Two young black Angus steers—not much more than a year old but already behemoths weighing more than one thousand pounds each—were standing on a pile of packed dirt and manure. They craned their necks skyward, soaking in the warm light. “Look at those guys right there,” said Paul Defoor, the 46-year-old CEO of Cactus Feeders, nodding from under his white hat. “Looking up at the sun, relaxing.”

Defoor sat in the cab of a gleaming white Ford Super Duty pickup as we drove through the middle of Cactus’s feedlot in the Panhandle town of Stratford, five hundred miles north of Roam Ranch and a stone’s throw from the Oklahoma border. We were in the midst of one of the densest concentrations of cattle on the planet. The Texas Panhandle is the epicenter of the state’s beef industry and anchors the southernmost portion of the South Plains beef belt—an area of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas where around half of the 34 million cattle harvested last year in the United States were fed and slaughtered. The Stratford feedlot is a key part of this industry, a metropolis teeming with 85,000 heaving beasts divided up neatly into two hundred pens organized in a checkerboard grid that sprawls out seemingly to the end of the earth.

Defoor comes off as almost lab-generated to be the CEO of one of the biggest cattle-feeding corporations in the world. A native of southeast Texas, he earned a PhD in ruminant nutrition from Texas Tech and looks and sounds like a movie cowboy, tall and trim with a singsongy voice and a fondness for folksy turns of phrase—“no two ways about it”—interspersed with scientific explanations of cellulase enzymes and rumen-hosted bacteria. He is proud of the massive machine that Cactus has built. The Stratford feedlot is just one of ten similarly sized Cactus facilities. Over the course of a year, Cactus is responsible for fattening up about one in every 25 steers and heifers slaughtered in the United States.

All of these Cactus-fed cattle spent the first seven or so months of their lives on what are known as cow-calf operations, traditional ranches where the animals graze on grass and follow the rhythms of nature. There are more than 700,000 of these ranches in the United States—around 130,000 in Texas—and as a rule they are small mom-and-pop concerns (the average Texas herd size is 34 head) that barely break even. (The running joke is that cow-calf ranchers “spend $1,000 to make $750.”) But when calves in the conventional beef system are weaned from their mothers, they enter a supply chain that’s very different from anything the bison at Roam Ranch will see. First, most weaned steers and heifers will move to a stocker operation, where they’ll spend another few months among thousands of other adolescent cattle maturing on grass. Then, when they’re around ten months old, they’ll be sold to a feedlot.

Critics of feedlots see them as the epitome of factory farming—a perversion of our agricultural roots. A ruminant mammal that has evolved to roam around a large area and eat grass is instead confined to a pen and implanted with growth hormones. It’s fed corn, which it wasn’t designed to eat. That raises its risk of digestive maladies and requires the use of large quantities of prophylactic antibiotics. The animals’ concentration in a relatively small area raises the risk of air and water pollution from the huge quantities of manure, the spread of disease in the animal population, and the possibility of antibiotic-resistant bacteria wreaking havoc on the human population. And the entire system is built upon industrial corn, which requires copious amounts of fast-depleting groundwater for irrigation. (An Environmental Protection Agency study of the beef industry found that irrigation for feed crops accounted for 96 percent of total water use in cattle production.) Corn farming also requires synthetic fertilizers to boost output (they cause nitrous oxide emissions and runoff and degrade soil health), and fossil fuels for fertilizer production and to power farm and transportation equipment.

“Feedlots for beef are absurd from an ecological point of view,” said the author Michael Pollan (The Omnivore’s Dilemma) when I spoke to him in February. “They may not be from an economic point of view. You have a system that is rational by one measure but completely insane by another.”

Defoor sees the feedlot system as rational by all measures, a triumph of efficiency that allows for the “most ideal use of the natural resources.” And as we drove around the Stratford feedlot, staring up at the hulking steel structure in which corn rations are milled, Defoor made it clear that this system was a highly calibrated industrial machine with every input tracked and optimized to the third decimal point. Cactus’s distinctly unsentimental official creed underscores this ethic: “Efficient Conversion of Feed Energy Into the Maximum Production of Beef at the Lowest Possible Cost.”

Yes, cattle are fed corn, Defoor said, but around 50 percent of their feed comes from agri-industrial waste, largely from the production of corn ethanol (an industry that wouldn’t exist without federal support, but that’s another story) that would otherwise end up in a landfill. Yes, cattle get hormones and steroids to force them to bulk up faster, but the “FDA corroborates that they’re safe,” and they save acres of corn. “You’d need maybe fifteen percent to twenty percent more feed to make the same amount of food if you didn’t use them,” Defoor told me.

Corn-fed cattle also produce less methane than grass-fed ones, mainly because corn is easier to digest. They also live shorter lives. Hormone-implanted, grain-finished cattle can reach their slaughter weight at sixteen to eighteen months, which means they spend fewer months belching methane than grass-finished cattle that don’t reach slaughter weight until close to thirty months. (Research is well underway to develop dietary supplements, among them a species of red seaweed, that may reduce cattle’s methane emissions even further.)

Defoor can cite plenty of data to back up his arguments. Since the mid-seventies, the U.S. beef industry has learned how to produce the same amount of meat with nearly forty million fewer cattle and has dramatically decreased its carbon footprint in the process, according to the UN. And the American system compares favorably to less-intensive cattle industries in the developing world. Every pound of beef produced in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa costs nearly three times more in greenhouse gas emissions—mostly because of less-efficient feed, older slaughter ages, and deforestation to create more pasture.

Brazil, which has the second-largest beef industry in the world and exports heavily to Asia, grazes much of its cattle on vast pastures carved from what until recently was Amazon rain forest. With the global appetite for beef projected to nearly double in the next few decades as economies in Asia and Africa continue to develop, the World Resources Institute has calculated that the planet might need an additional 1.5 million square miles of pastureland—an area larger than India—to meet demand.

Modern Texas cattlemen like Defoor have their own endangered future to face. The Panhandle is drying up. The Ogallala Aquifer, which supplies nearly all of the region’s water, has diminished rapidly in the past two decades, largely a consequence of irrigating land where rainfall is insufficient to support the farming of most crops. (That description today fits most of the land in the western half of Texas, which, before groundwater irrigation, was devoted mainly to grazing.) Tilling the land and the overuse of synthetic fertilizers, meanwhile, has diminished the soil’s ability to retain water, which has exacerbated the problem. “Only with the advent of the ability to pull water from the Ogallala has any civilization with the exception of the Comanches been able to thrive here,” Defoor told me.

While we were driving through the grid of feedlots, Cactus’s beef division president, Tres Hess, stopped the truck next to a field of wheat, where a few small cattle were grazing. “As our water table continues to drop, we’ve tried to find other uses for our land,” Hess said. “This ground in the past has been used to grow corn and cotton.”

The field wasn’t unique. Cactus no longer grows corn, which it determined requires too much water. And all of the company’s fields are now pastures for pre-feedlot stocker cattle, which cycle through a version of a rotational grazing that, while far less intensive than what Collins and Forrest are doing at Roam Ranch, follows similar principles. Defoor said Cactus’s goal was to “keep the sun off the dirt” by using cover-crops year round. Transitioning the fields to grazing is boosting soil health, he explained. He calculated that increasing the soil’s organic matter by one percentage point would allow it to retain an additional 20,000 gallons of water per acre—the equivalent of three inches of rainfall. He thought Cactus could increase the soil organic matter of its fields by at least twice as much.

Cactus still fattens up its feedlot animals on huge quantities of corn grown elsewhere, and it’s certainly not switching over to small, multispecies, chemical-free farming, but it is also rebuilding the soil of its own fields and doing it at a scale—50,000 stocker cattle—that is far beyond the reach of an operation like Roam.

“Have you heard this term regenerative agriculture?” I asked Defoor. “Do you think that’s what you’re doing?

“No doubt that’s what we’re doing,” he said.

The Slaughterhouse Four

A Holstein cow—enormous and aged—ambled down the ramp of the big cattle truck at Caviness Beef Packers, joining a few hundred other animals in a temporary holding pen, blissfully unaware that she was only a few hours from her death.

The Holstein hadn’t come from a Cactus feedlot, or any feedlot at all. She’d spent her mature years at a dairy. But she was no longer producing enough milk to justify the cost of her feed, and her owner had sold her for slaughter to Caviness, which is based in the Panhandle town of Hereford, the self-proclaimed “beef capital of the world.” Since the Holstein hadn’t been “finished,” her meat wouldn’t grade high on the USDA marbling scale; her fate was to become a thousand pounds of hamburgers and sausage.

The end would come quickly. She would leave her holding pen in an hour or two, enter a maze-like concrete chute, and eventually arrive at the exterior wall of Caviness’s knocking room. As soon as she stepped inside, a young guy with bulging arms would be standing on a platform above her, holding a metal contraption that looked like a stage klieg light. The man would touch the end of the contraption to the center of the cow’s forehead, a little above the eyes. He’d press the trigger and launch a metal rod a few inches into the Holstein’s skull, and her life would be over. She would drop immediately onto a conveyor belt, her tongue flapping out of her mouth as chains were affixed to her feet. A few moments later, as she entered the factory floor hanging upside down, another worker would slash her carotid artery, sending blood gushing to the floor.

I’d asked to tour Caviness because I knew it was something of a rarity in the industry, a multigenerational family operation—it’s run by Terry Caviness and his sons, Trevor and Regan—that serves both the conventional beef supply chain and smaller producers. Caviness slaughters and processes around two thousand animals a day, including older ones, like that Holstein, that are no longer profitable to keep alive, and finished cattle from ranchers and feeders. If you’ve ever bought all-natural or grass-finished beef from Whole Foods in Texas, it was harvested at Caviness. If you’ve ever ordered a 44 Farms brisket or a HeartBrand Akaushi ribeye at an upscale barbecue joint or steakhouse, it was harvested at Caviness. If you’ve ever enjoyed a hamburger at P. Terry’s or Hat Creek, it was harvested at Caviness.

Whenever advocates of regenerative agriculture talk about creating a new beef system—one that looks more like nature than a factory—it doesn’t take long before they have to grapple with a seemingly insurmountable problem. As Nicolette Hahn Niman, a rancher and lawyer who wrote the 2014 book Defending Beef, put it to me, “The slaughterhouse is the bottleneck of the sustainable meat movement.” Instead of a robust system of small and mid-sized regional slaughterhouses that would enable beef cattle to be harvested all over the country, the beef industry has built enormous slaughterhouses close to the nation’s feedlots, which means that a disproportionate number are in the corn belt. Four large corporations—Tyson, Cargill, JBS, and National Beef—control 85 percent of the U.S. beef packing industry, operating plants that can slaughter and process as many as five thousand animals a day—almost all of them sixteen-to-eighteen-month-old cattle straight off the feedlot.

This highly concentrated system at once forces uniformity on suppliers and unlocks great economies of scale and global trade. At Caviness, a series of three giant metal levers strips the hide clean off the carcass to be prepared for shipment to leather-goods factories in China and Mexico. A worker with a vacuum tube sucks out the animal’s spinal cord, a precaution put in after the spread of Mad Cow Disease. The animal’s underside is sliced open to extract the stomach, intestines, kidneys, and liver, and some of the organs are placed into boxes affixed with labels in Arabic and sent to Egypt. The meaty sides eventually end up in the deboning room, where several hundred plant workers standing in close quarters slice and hack at steadily diminishing hunks of muscle and fat that hurry by on a conveyor belt. The trimmings get made into ground beef blends. The flat of the brisket and the eye of the round go to jerky makers. The subprimal cuts are vacuum sealed and placed in cardboard boxes bound for supermarket or food service–owned facilities, to be sliced up further into steaks or other consumables. The work is grueling, and employees on the line wear earplugs to block the rattle of the machines, which also makes conversation nearly impossible.

Packing plants’ deep reliance on human labor (“the physical work of deboning is the same way it’s been done since God made the first cow—with a hand knife,” Terry Caviness told me) eventually became a major story line of the COVID-19 pandemic. I visited Caviness on a Wednesday in mid-March, when the country was still hoping it might avoid widespread outbreaks. Within weeks, packing plant workers were getting sick in huge numbers, and packing plants became the bottleneck not just of the sustainable meat movement but the entire conventional beef supply chain. That’s the thing about centering the process around such enormous plants: Slow down the line at just a few of them and there are ripple effects on price and inventory at supermarkets and burger joints across the country. Some Wendy’s locations had to stop selling beef. The episode was ugly: One industry representative blamed the out-of-control spread in facilities on the living circumstances of immigrant employees being “different than they are with your traditional American family.” (Many meatpacking workers live in communal apartments and homes and send remittances back to their families in their native countries.) Soon a coalition of groups concerned with human welfare, not animal rights, was urging consumers to avoid meat. Caviness itself saw 10 percent of its 1,150 workers test positive for COVID-19 as of the end of July.

Even before the pandemic, disparate voices within the industry were calling for a rethink of the packing plant system, complaining that the Big Four have hoarded too much of the profit in the beef supply chain and that the dearth of competition at the top has made it almost impossible to make money at the bottom. (The Department of Justice, meanwhile, has reportedly subpoenaed the Big Four beef packers as part of an ongoing antitrust probe.) A lot of ranchers want out. The average age of a farmer or rancher in the United States is now nearly 60, and one analysis posited that there would be zero ranch operators younger than 35 by the year 2033. The margins are slim to nonexistent, the work is nonstop, and rising land values have often made it more profitable to sell out to wealthy urbanite weekenders.

Wendel Thuss, a 41-year-old Austin-based cattleman and entrepreneur, told me he was convinced that the future of ranching depends on moving past the Big Four. When I met Thuss at the NCBA conference in San Antonio, he was conspicuously urbane, skinny and slight. He looked more like an aging indie rock drummer than a rancher. “I’m not wearing the uniform,” Thuss said. “I like to say I’m all cattle and no hat. I get away with it because I own a lot of cattle.”

Thuss has started a cattle-sales smartphone app called AgEx that offers ranchers new avenues to sell their animals outside of the auction-barn system that leads into the big feedlots and packing plants. He thinks the Big Four’s hold on the industry is expiring. “They’re like Sears, Circuit City, or the taxicab medallion holders—the world has shifted around them,” he said. In their place—or at least alongside them—he envisions the rise of a new system of medium-sized, independently owned cooperative packing plants. Facilities like that would enable more producers to adopt a business model in which they’d own their animals from birth to slaughter, assuming more risk but also more potential upside.

Like Forrest and Collins and Moorman, Thuss radiates an entrepreneur’s optimism in the face of long odds. But the pandemic offered a preview of what his dream might look like. Small packing plants have been booming lately. Davey Griffin, a Texas A&M extension professor who is the executive director of the Texas Association of Meat Processors, which represents independent slaughterhouses, told me that since the start of the coronavirus crisis, “every time I turn around I get another phone call from somebody who wants to know more about starting a new plant.” Hannah Null, a former corporate senior manager at Walmart who now runs the Bluebonnet Meat Company, in Trenton, with her brother, Ben Buses, told me that in normal years they book slaughter dates two or three months in advance; nowadays, with more local customers looking to buy beef from pasture-raised animals, they are completely scheduled through May 2021.

The trend is barely a blip to the major meat-packers at this point. You’d need 250 Bluebonnet Meat Companies to make up for the production capacity of just one Caviness, which is itself less than half the size of some Big Four facilities. And it’s anything but guaranteed that a bunch of small plants would somehow be cleaner and safer, in aggregate, than a handful of giant ones.

When I was at Caviness, Terry and Trevor drove me out to a field next to their plant that was covered with tarps that ballooned up from the ground. They looked like tennis domes. They were, in fact, collecting methane from the wastewater-filled lagoons beneath them. The recaptured gas would be pumped back into the plant and used as an energy source.

Terry told me he thought the industry was making a “better, more wholesome product” than when he began working beside his father, Pete, in 1969. Trevor emphasized that the scale of the slaughterhouses means that they can invest in infrastructure and access the worldwide market, monetizing every ounce of the animal. The industry might not be perfect, but it’s doing more with less, he said, which he called “the definition of sustainability.” To him, beef is a simple proposition that is perfectly served by the current system: “Consumers want consistency and quality. Prime is prime, choice is choice—the rest is just branding and marketing.”

Beefing Up the Options

“For the last forty years, we’ve had this mantra of ‘bigger is better, more efficient is better,’ ” said Matt Hamilton. I’d just shaken his hand, and already he was running hot. “Is it FDA approved? Is it USDA approved? Yeah? Well then, Hoorah! Hoorah!”

Hamilton, the 44-year-old owner of Local Yocal Farm to Market, a butcher shop in downtown McKinney, is no country hippie. He’s well steeped in the ways of conventional agriculture. He grew up on a farm in Oklahoma and majored in agricultural economics at Oklahoma State, and many of his friends have gone on to work in Big Beef. The Saturday afternoon “Steak 101” classes he teaches in downtown McKinney helped land him an endorsement deal with a cowboy-hat company. But he thinks American beef has gone too far, too fast, and it’s time to take a step back.

“We have three flavors of beef,” Hamilton said, once we’d entered his store. “Because some people want the Ferrari and some people can only afford a Toyota.” He nodded to a ribeye, a tenderloin, a New York strip, and some ground beef occupying one side of the glass meat case. This meat, his Toyota—and Hamilton wanted to make clear it was a nice Toyota, maybe even a Lexus—came from 44 Farms–sired Angus steer slaughtered, sliced, and sealed up at Caviness. It had prized genetics, had been raised without antibiotics or growth hormones, and has been championed by renowned chefs like John Tesar in Dallas and Chris Shepherd in Houston. Next to the Angus was Hamilton’s Ferrari, the Wagyu, a “world-class beef experience” with otherworldly marbled meat from cattle whose genetics could be traced back to Japanese herds.

At the other end of the case was Hamilton’s grass-finished beef, all of it harvested from a heritage breed of cattle called the Murray Grey. Hamilton had raised the animals personally just a few miles away from Local Yocal’s front door. In Hamilton’s car analogy, the Murray Grey beef is something akin to a Lotus—temperamental, not for everyone, but capable of astonishing performance with the right driver and conditions.

Hamilton is an evangelist for this meat, and grass-finished beef needs evangelists. Mention grass-finished beef to most cattle people, and they’ll frown in disgust. Grain-finished beef is tender and fatty. Grass-finished beef is leaner and chewier, not well suited to the American palate. Hamilton, of course, doesn’t see it like this.

He will wax poetic about how grass-finished steaks—particularly his grass-finished steaks—are as complex and nuanced as Napa Valley cabernets, while conventional feedlot beef is as sweet and simple as supermarket white wine. He will offer up disquisitions on the right breed and forages necessary to make grass-finished beef that’s sufficiently fatty and tender, and he’ll be the first to tell you that making good grass-finished beef is tricky—more dependent on the weather and individual ranchers’ expertise than are the consistent, scientifically calibrated products coming out of places like Cactus Feeders. He also knows that most Americans who’ve tasted grass-finished beef haven’t had the good stuff, since the grass-finished segment of the market has been dominated by cheap imports from Australia and South America.

Hamilton’s butcher case is a good encapsulation of his vision for the beef industry. He’s a businessman who wants to reach as many people as possible, and he is open to different models of beef production even as he holds up his local, pasture-raised, grass-finished steaks as the epitome of good eating. What Hamilton doesn’t like is what he calls “the freight train”—Big Beef, with its addiction to yield-enhancing drugs and cost-cutting measures. He’s frustrated that independent ranchers don’t have much choice in how they operate. He doesn’t like that Americans are willing to eat meat from hormone- and antibiotic-treated animals just because it’s cheaper and the feds have given a thumbs-up. He doesn’t like how disconnected American food has become from its sources. “They did a study and found there can be 130 strains of DNA in one hamburger,” he told me, wearily, as we were leaving the butcher shop. (It’s true.)

Hamilton has a romantic view of how to set things right, and he’s built a small business empire based on it. He has the butcher shop and raises his cattle, and he invested in a local packing plant and, most recently, opened a restaurant, the Local Yocal BBQ and Grill, in an airy warehouse with Wagyu on the menu and a wall of whiskeys behind the bar. The idea is locally raised meat, sold locally, by local people making good wages.

In the back of Local Yocal, Hamilton showed me an entire side of his grass-finished beef that was hanging from a meat hook. This was once a common sight at American butcher shops. Now it’s almost impossible to find. To get a side of beef, Hamilton had raised the animal in McKinney, then taken it 25 miles northeast to be slaughtered at Hannah Null’s eight-cow-a-day Bluebonnet Meat Company. Hamilton likes harvesting his meat this way, but the numbers don’t add up. At Bluebonnet, hides and kidneys don’t miraculously get shipped off to China and Egypt for a profit. Another company must be paid to cart those bits away. At a place like Caviness, Hamilton could earn hundreds of dollars for the “drop,” meaning he’d get his meat harvested, essentially, for free. But Hamilton couldn’t send his grass-finished cattle to a bigger packing plant even if he wanted to. He doesn’t raise enough animals to get in the door.

The result of all that, of course, is that Hamilton’s beef is as expensive as it is exquisite. When I placed a mail order for some of his grass-finished filet mignon, it cost $38 a pound. I could get conventional USDA Prime of the same cut at Costco for less than half the price, and it would taste great. Still, Hamilton’s business is successful, and since the pandemic shutdowns began in March, sales at his butcher shop have doubled. Other boutique producers around the country, from local organic farms to far-flung ranches offering mail-order meats, are also experiencing booming sales. This hardly means that the end of conventional beef is here. The big packing plants are now slaughtering more animals than at the same time last year, making up for the earlier COVID-19–related slowdown. The USDA projects the country will produce 27 billion pounds of beef in 2020, a drop of less than one percent from last year, and nearly all of that is conventional beef.

But the pandemic has exposed systemic flaws. The rise of plant-based meats and a steady drumbeat of bad press have opened more people’s eyes to alternatives. If small packing plants are booked solid a year out, then maybe some of those would-be entrepreneurs calling Davey Griffin really will build new facilities to harvest local beef. If Hamilton can double sales at Local Yocal Farm to Market, then maybe that signals enough consumer demand that other butcher shops will begin offering an alternative to the conventional supply chain—eventually nudging down the price. If the ideas of regenerative agriculture continue to spread, then maybe more water- and soil-depleting cornfields will become water-retaining, soil-enhancing grasslands. And maybe more of the organizations transforming those lands will be Big Beef pillars like Cactus Feeders, for whom renewing natural resources may be as much of an economic necessity as an ecological one. Why couldn’t every one of those solutions coexist on the industry menu, even if they don’t show up together on one plate?

As we were enjoying a lunch of Wagyu sirloin, Hamilton told me he worries that the industry doesn’t appreciate that the next generation, twentysomethings like his daughter, have choices that previous generations didn’t. Young adults could ensure a future of burger nights here and abroad, or they could look at the problems of beef and bunch up their noses, as folks did in the eighties, only this time they could turn to Beyond Meat or whatever comes after that. “We’ve got to say to that person, ‘We’ve fixed our problems, it’s okay to eat beef, and here’s why it’s okay.’ ” He locked eyes with me as he chewed a bite of his velvety steak. “If we don’t adapt and create the products that the next generation wants, we’re not going to have a beef industry.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Quest for Better Beef.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- The Wild West of Wagyu

- Longreads