The Deep Roots of Sexual Policing in America

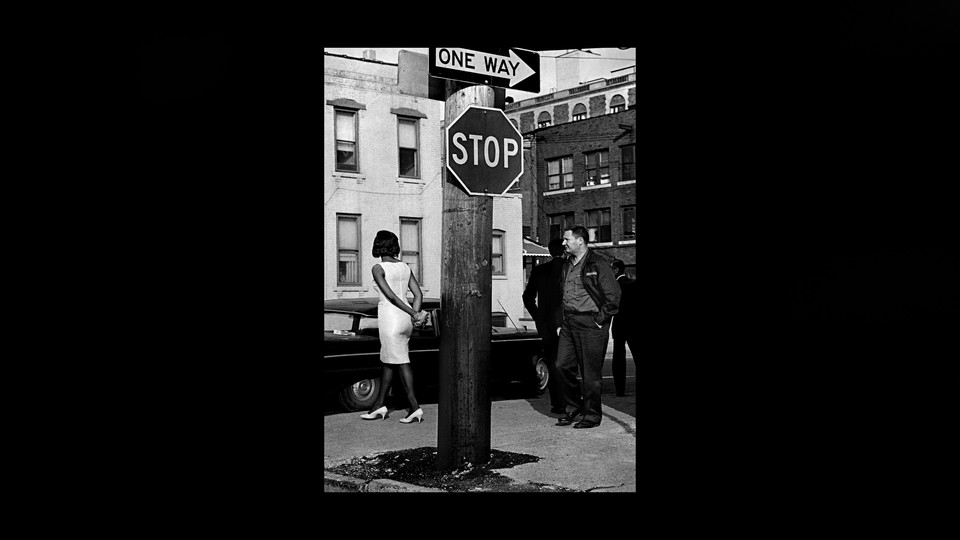

A new book explores the way anti-loitering laws targeted Black women.

Misdemeanors—minor offenses typically punishable by no more than a year in prison—account for more than 80 percent of criminal cases in the United States. In three large municipalities, just 4 percent of a typical police officer's shift is spent on violent crimes, while the majority of their time is devoted to duties like responding to traffic incidents or other disturbances, according to a 2020 New York Times analysis. So why are the police often portrayed, and imagined, as crime fighters?

This mismatch has done more than bolster the police’s public image; it has also served as a rationale for policy choices. Police are equipped with military-grade weapons acquired through federal programs. They are inappropriately trained to be warriors when they should be learning how to act as social workers or street-safety monitors. Unsurprisingly, officers adopt a battle-ready mindset when responding to domestic disturbances or conducting routine traffic stops, too often with devastating consequences.

The historian Anne Gray Fischer offers a surprising explanation for the disconnect between the myth and reality of policing in her book, The Streets Belong to Us: Sex, Race, and Police Power From Segregation to Gentrification. She argues that the “legal control of people’s bodies and their presumed sexual activities,” especially when it came to Black women, supported the notion that aggressively pursuing public-disorder offenses, such as disturbing the peace or urinating in public, would prevent more serious crimes. This is essentially the theory behind what is known today as “broken windows” policing, a key law-enforcement strategy. Fischer argues that it was the sexual policing of Black women that laid the legal groundwork for “mass misdemeanor policing” and legitimized the police’s broad powers to exercise discretion.

The history that Fischer traces in her book is revelatory for several reasons. Most accounts of crime and punishment focus on men, particularly Black men, not women. Sex work itself wasn’t widely criminalized until the early 20th century, when moral crusaders, alarmed by unfounded fears that white women were being forced into prostitution, banded together to abolish what they called “white slavery.” As the term suggests, officials at the time were not concerned with the degradation of Black women, who were arrested for prostitution at far lower rates than their white counterparts. Moreover, many police leaders maintained that vice wasn’t a real crime, and didn’t prioritize morals enforcement. The Streets Belong to Us shows how dramatically attitudes toward vice and crime changed over the course of the past century.

According to Fischer, two trends coincided in the mid-20th century that turned law enforcement’s attention to Black women’s sexuality. First, white people in cities throughout the country decamped to the suburbs, so by 1965, many urban areas had large Black populations. Second, sexual mores loosened up, requiring the revision of Progressive-era laws that had criminalized nonmarital sex, “with or without hire.” As a result, a new distinction emerged between legal and illegal sexual conduct based on race. For middle-class white women, sex outside of marriage tended to be understood as a private activity and decriminalized (albeit considered a psychological disorder), whereas for Black women, who were associated with the “ghetto” or “slum,” it remained criminalized and came to be seen as an example of public disorder.

Certainly, police targeted Black men too. But, Fischer argues, municipal authorities zeroed in on eliminating sex work in order to lure investment and tourism back to cities, which by the 1970s were suffering from deindustrialization and suburbanization. Political leaders and private developers alike believed that commercial sex caused street crimes by attracting muggers and robbers. They would not have challenged a New York police captain’s unsubstantiated claim that “if it weren’t for the street girls, the crime rate would hardly exist.”

Fischer uses Los Angeles, Boston, and Atlanta as case studies to illustrate how cities nationwide cleaned up their downtowns for development in the late ’70s and ’80s. First, they passed laws against loitering for purposes of prostitution. No longer did officers have to gather evidence of actual prostitution to arrest women; now they could apprehend them just for standing on the street or talking with a man. As a New York court explained when justifying this discretionary power, for “any trained law enforcement officer, it would be a simple task to differentiate between casual street encounters and a series of acts of solicitation for prostitution, between the canvas of a female political activist and the maneuvers of a Times Square prostitute.” Vague laws that allowed the police to determine the difference between a lawful and unlawful presence in public made arrests much easier to make.

With anti-loitering ordinances in place, city leaders then insisted on their strict enforcement, and arrest numbers shot up. Although Fischer’s book doesn’t provide statistics consistently across time or across the three cities—to be fair, crime statistics are spotty—the numbers that do appear are telling. Fischer found that arrests for morals offenses skyrocketed throughout the country in the 1980s. In Los Angeles, prostitution-related arrests almost doubled from 1974 to 1984. Statistics from Atlanta highlight the racial disparity in morals enforcement: From January to August 1983, 234 white women were charged with disorderly conduct or prostitution-related offenses, compared with 778 Black women. These figures, however, don’t capture the harassment, physical abuse, and sexual violence that women, especially Black women, experienced. In the 1970s, advocates for sex workers’ rights alleged that police had burned women’s hands on the hot hoods of running cars or raped them. Black women were also picked up by police, and then stranded in all-white neighborhoods that were hostile to integration.

Officers paid an inordinate amount of attention to low-level public-disorder offenses because business owners and city officials demanded it. But the police were more than willing partners. The early-20th-century idea that professional police shouldn’t waste their time on vice patrol was forgotten once officers realized that making prostitution-related arrests sent the message that they were serious about crime. Governments at the local, state, and federal levels reaffirmed that message by financing specially trained and equipped anti-crime tactical units that mainly patrolled for disorderly conduct. The most significant source of funding came from the federal Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, established in 1968, which disbursed almost $10 billion to state and local police departments before it was abolished in 1981.

Fischer explains how poor Black women shouldered the costs of gentrification and police militarization. Her book goes on to make an even stronger causal argument: Modern police’s discretionary power was “built on women’s bodies.” Misdemeanor morals policing, Fischer points out, predated the “broken-windows” theory that George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson introduced in a 1982 article published in the Atlantic. But in fact, Kelling and Wilson maintained that what they called broken-windows policing had been occurring for centuries. “Young toughs were roughed up, people were arrested ‘on suspicion’ or for vagrancy”—predecessors to anti-loitering laws—“and prostitutes and petty thieves were routed,” they explained. Stop-and-frisk was used to similar effect in poor and minority neighborhoods. The historian Robert M. Fogelson provided an example of this controversial practice in his 1977 book, Big-City Police: In the 1950s, the police in San Francisco launched Operation S (for “saturation”), which entailed mass stops, questioning, and frisks, as well as arrests for vagrancy.

Sexual policing wasn’t the only historical predecessor to broken-windows policing, nor was it the only legal precedent. From the early to mid-20th century, many judges and legal scholars suspected that vagrancy laws were overly vague, giving arresting officers too much discretion, and the Supreme Court effectively overturned them in 1972. In response, states and municipalities passed laws against “loitering with intent” to commit prostitution, as Fischer examines, which was another attempt to authorize proactive, preventative policing. Later, during the War on Drugs in the 1980s and ’90s, some cities began prohibiting “loitering with intent” to engage in drug activity. Morals enforcement, in other words, provided the legal template to legitimize the kind of policing that was once considered constitutionally dubious.

So, too, did the Supreme Court’s decision in Terry v. Ohio (1968), which permitted stop-and-frisk if an officer believed that an individual was armed or about to commit a crime. Allowing police to take action based on their suspicion that any crime is afoot bestows an even broader grant of discretionary power than laws prohibiting prostitution-related conduct.

The origins of discretionary policing may not lie solely in the late-20th-century practice Fischer highlights in her book, but it is nonetheless an important, and often overlooked, part of the history of modern law enforcement in the U.S. While movements like #SayHerName highlight police violence against Black women today, The Streets Belong to Us shows us its deep roots in our history, our laws, and our cities.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.