Ottawa police are hiring 80 officers. But, as public scrutiny of policing grows, who wants to be a cop?

"We have to evolve as the workforce evolves as well. Policing traditionally hasn't done that."

Article content

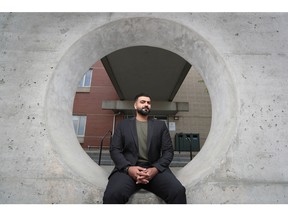

Ahmad Zeim Ali remembers the first moment he knew he wanted to become a police officer. He was working as a screener at the Ottawa airport, unsure of his career path, when a sergeant with the Ottawa Police Service told him he would make a good cop.

It wasn’t a career Zeim Ali had considered. He grew up in Ottawa community housing, in a neighbourhood where many teenage boys, himself included, didn’t always have positive interactions with police.

“A lot of kids my age, they hated the police,” he said. “It’s almost as if I needed to hear that in order to encourage myself to think about pursuing a career in law enforcement.”

Now, Zeim Ali uses the experiences he had as a teenager as motivation. He wants to be a positive force in the community where he grew up, and he wants to do so by being a good cop.

“I want to go back to where I grew up and just approach kids and ask them questions and have just a normal conversation and show them that this uniform, I’m not a scary person, I’m just like you, I want to have a talk with you, I want to know what your concerns are and we go from there,” he said.

Zeim Ali is one of possibly thousands of candidates vying for 80 open officer positions with the Ottawa Police Service this year. As police services face increased scrutiny and community pressure to change, police recruiting is changing, too.

Potential hires increasingly look like Zeim Ali: experienced, bilingual, rooted in the communities they will eventually be patrolling, and, despite more negative portrayals of police in media and online than ever before, motivated that they can improve the institution from the inside.

In 2020, a storm of criticism surrounded the police after George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis. Sgt. Maria Keen, a veteran OPS office involved with the service’s recruiting efforts, recalled how, at that time, there were fears inside the OPS that the service would struggle to recruit.

“My supervisors, people were worried, saying, ‘How are we going to overcome this? Are people going to apply?'” Keen said. “My answer and my recruiting methods at that time were to say to people: ‘Be part of the change.’ If you feel strongly that police officers aren’t doing what they’re supposed to be doing or you’re critical of them, be part of that change.”

By the end of 2020, the OPS had received 2,700 applications, Keen said; recruiting had actually increased.

“We took down a lot of the barriers to applying. That probably helped,” she said, “because we were trying to broaden our recruitment efforts to marginalized communities, racialized communities, people who normally didn’t think of policing as a career, because we want to reflect the community.

“I’ve been here 30 years,” Keen added. “The Ottawa police has always wanted to hire people to reflect our community and of course, in the 30-some-odd years I’ve lived here, the face of Ottawa is changing. There’s more diversity in our city than when I first moved here, so of course, we want to do that. The hurdle is, does the community want to embrace that?”

The OPS’s 2020 and early 2022 classes were its most diverse ever; more women and minorities are now patrolling Ottawa’s streets.

But there is a growing concern in police departments across Canada about their ability to continue to attract — and retain — young officers. At a police services board meeting on May 30, OPS leaders explained some of the challenges they were having with recruitment. Among them: a difficult work-life balance marked by rotating shift work and a desire to have recruits commit to a potential lifetime career.

“We have to evolve as the workforce evolves as well,” acting chief Steve Bell told the board. “Policing traditionally hasn’t done that. It could market itself as, ‘Come work for us for 30, 35, 40 years. We’re your career cradle to grave.’ That doesn’t resonate in the workforce the way it used to.

“We would love for you to stay with us for a long period of time, but we also realize most people will do two or three careers in their lifetime. We have to be adaptive to that and be responsive to that because I think we cut off some of our recruiting opportunities when we say to people, ‘If you don’t come here for 30 years, we don’t want you.'”

Now more than ever, potential recruits are aware of how difficult it is to be a police officer. And it is a job made more difficult, union leaders say, because of low staffing, which is reaching a crisis level in Ottawa, according to Brian Samuel, the interim president of the Ottawa Police Association.

“We’re getting busier because the city of Ottawa is growing exponentially,” Samuel said in an interview. “We’ve been telling the police service for the last five years: ‘You need to hire more, you need to hire more. There’s a staffing crisis, you’re going to have a staffing crisis.’

“The hiring didn’t meet up to the standards to replace both through attrition and just through new hires.”

As hiring opportunities for the OPS become increasingly rare, there is competition for job postings. Zeim Ali has applied to the OPS in the past, but was unsuccessful. He’s hoping this year that his experience, which includes a police foundations diploma from Algonquin College and extensive volunteering in his community, will set him apart.

Experience in volunteering, now sometimes referred to as community engagement, is key to getting hired in the modern policing world, according to Jill Reeves, program coordinator and academic advisor at Algonquin’s Police and Public Safety Institute.

Officers, like in the OPS’s neighbourhood resource teams, are increasingly expected to build bridges with communities that may have negative views of police — whether from personal experiences or from witnessing police brutality on social media and in the news.

In her classroom, Reeves said she doesn’t shy away from hard discussions. “I think that we’re very honest,” she said. “I’ve definitely noticed a trend where students are coming to me better and better informed about what is in the news … They don’t shy away from those issues at all.”

During their time at Algonquin, in addition to a plethora of courses about criminal justice, sociology, victimology, and fitness courses, police foundations students are encouraged to “get out of their comfort zones,” Reeves said, “and learn as much as they can about communities that may interact more with the justice system than others.”

But, even with police foundations as a background, it may take years working another job — like security — before an aspiring police officer is accepted. The application process takes motivation, Zeim Ali said, a quality he said he was not lacking.

Before coming to Canada, he spent his childhood in war-torn Iraq and remembered how, amid the presence of bombs and missiles, his family fled to the woods, living off of dates and bread. He arrived in Ottawa in 2004 and feels a deep sense of connection with his community.

“This country and this community have given me so much,” he said, “but most importantly to me, my family, it has given us a home, a safe place to go to sleep without worrying about bombs going off or planes flying above. I owe it to this country and my community to serve it.”

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.