Before Emoji, There Was The Print Shop

How a collection of simple graphics from the early days of the personal computer shaped today’s visual shorthand

Once upon a time, long before there were smartphones or emoji, computer graphics were crude, pixelated, and often came screeching out of a dot matrix printer.

Those who wished to use their computers to express themselves visually and without text had limited imagery. Three decades ago, there was no crying cat. There was no smiling poo. There was no suggestive eggplant. But in these otherwise dark ages, we had The Print Shop, a cultural phenomenon that infused an otherwise text-based world with images—part of a long tradition that can be traced from the rare emoticons of the 19th century to Zapf Dingbats to The Print Shop to emoji.

In 1984, The Print Shop was among the first class of publishing programs for personal computers. It was stationary software, in a way, designed for making banners, signs, greeting cards, and so forth—forms of communication that are, generally speaking, more about displaying a message than one-on-one communication, where emoji thrive. (That being said, performative emoji use is an art all its own.) Emoji was first created, according to its inventor, Shigetaka Kurita, as a way to add more texture and nuance to phone-based text. In the early 2000s, cellphone weather reports particularly bothered him, Kurita told Ignition magazine, because they were all text-based with none of the icons—like sunshine or clouds—that he expected on other platforms.

Looking back, the relative lack of variety notwithstanding, The Print Shop’s image library wasn’t so different conceptually than today’s emoji. In my estimation, with the help of the Internet Archive’s emulated version of The Print Shop’s 1984 edition, about 80 percent of the collection of graphics from back in the day has a modern emoji equivalent. A lot of it is what you’d expect—holiday-themed imagery, for instance, and other designs that could be conceived as broadly applicable.

For instance, there is birthday cake:

A top hat:

And an apple:

The Print Shop also had a heart, a gift box, a jack-o’-lantern, a menorah, a Christmas tree, a rose, ice cream, champagne, a candle, a light bulb, a piano, a trumpet, music notes, a skull, a sailboat, a train, a money bag, an alarm clock, a question mark, a yin-yang, and several other images that have carried over to the world of emoji. But there are some key differences between these visual worlds. The most obvious is the lack of people in The Print Shop. The top-hat figure, above, is representative of how awkwardly The Print Shop handles humans. Similarly, the software’s graduate is faceless:

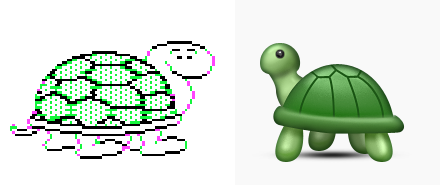

The only images with faces, in The Print Shop’s universe, are the animals—which raises another distinction. Both Print Shop and emoji deal with this category, but emoji creatures are (for the most part) more realistic, while The Print Shops’s critters are almost entirely cutesy and anthropomorphized.

Except, of course, in one disturbing example from the 1980s. After a screenful of smiling beings—dog, cat, teddy bear, turtle pig, bunny, penguin, dove, butterfly—you get a carcass:

Which, to be fair, also exists in emoji form, only it’s grouped with food—not animals:

And though emoji clearly wins in numbers, The Print Shop had a few unique images of its own: a stork, a holiday wreath, a cupid, a drum, and a butterfly. The Print Shop still comes out on top in some other regards. It has a cooler robot than the Apple iteration of the emoji version:

Same goes for The Print Shop rocket, which appears to be in the process of launching:

I also prefer The Print Shop’s spacescape, which is less Earth-centric or star-focused than similar views of space depicted in emoji.

More broadly, both take a similar and decidedly nostalgic approach to technology. The Print Shop has an antique car and a quill and scroll; emoji has a CD, a pager, a VHS tape, a hard disk, and a fax machine.

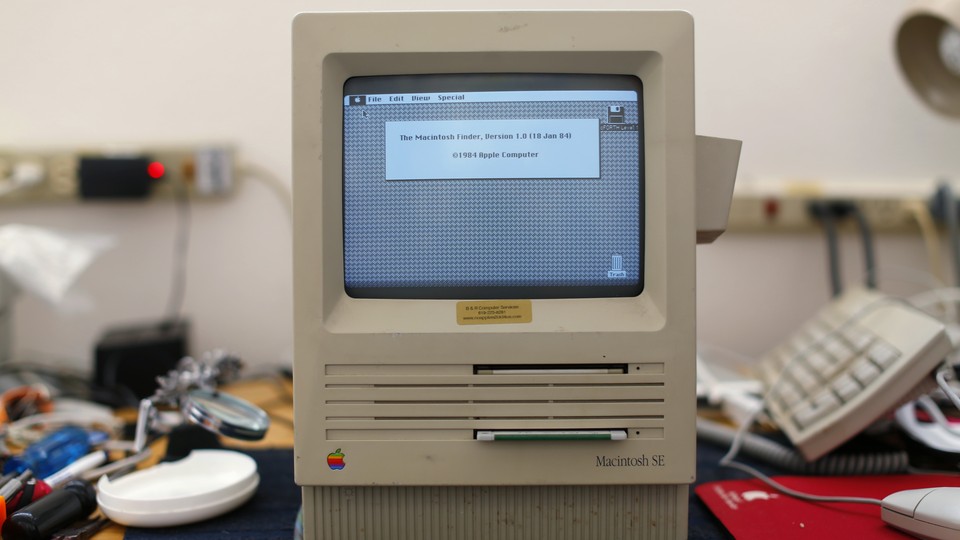

The Print Shop’s image library also has a delightfully old-school floppy disk. Of course, at the time when the software was popular, floppies were still new. My favorite technology imagery from Print Shop is probably the computer, which, incidentally, features the closest thing to a modern-day emoji on its screen.

In 1984, when The Print Shop was released, graphics were a new and playful aspect of computing—one that at least one prominent tech critic at the time declared a passing fad. (He predicted, wrongly, that The Print Shop would never sell.) After all, the shift from text-heavy to graphical video games didn’t begin until around 1979. And the first graphics-oriented software for business presentations came out around the same time as The Print Shop.

Today, text and imagery—emoji, specifically—are coalescing, both in personal conversations and professional ones. Whether that represents the emergence of a new kind of language is up for debate. But the implications for human communication mean new shades of nuance, added layers of meaning, and, in some ways, a throwback to a time when computerized graphics were new.