Blood utilization has become a more focused effort over the last decade. Accrediting bodies like the Joint Commission have asked hospitals and health systems to actively monitor overutilization of patient therapies. One of the top five most commonly overutilized therapies has been blood transfusions, as identified by the American Medical Association.1 The American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely program addresses waste in healthcare. One of the Choosing Wisely initiatives “Why choose two when one will do?” is to teach clinicians to only order blood products when truly necessary, and only one unit at a time.2

The Department of Health and Human Services National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey (NBCUS) has identified a decreased trend in blood collections over most of the last decade.3 Evidence supports that this trend is most likely due to the decreased utilization of blood transfusions in hospitalized patients in the United States since 2011 because of nationwide efforts to help quell the use of blood products when they may not be medically necessary.4

A multitude of studies have supported the Choosing Wisely recommendations of a more restrictive, rather than liberal, transfusion practice in stable patients. The studies have found this approach to be more effective, and ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.5,6,7,8

Orthopedics specialties, for example, have seen substantial decreases in the use of perioperative blood transfusions since implementing wide use of an inexpensive drug called tranexamic acid, which helps decrease bleeding associated with certain surgeries.9

Not without risk, blood transfusions can lead to other problems, namely transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), and other transfusion-specific adverse events; immunomodulation; increased rates of healthcare associated infections; and increases in the hospital length of stay.4,5 Increased hospital stays can lead to poor patient outcomes, decreased Medicare reimbursement rates, and an overall increase in patient-care costs.

The roles of institutional blood utilization committees — in addition to monitoring usage/wastage statistics and crossmatch/transfusion ratios — have evolved in recent years in response to the utilization efforts discussed here.

Like other institutions, Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center, formerly known as the University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro, also has a committee that focuses on the overutilization of blood products. Historically, the committee has achieved its goals by:

- Peer-to-peer discussions, which help to educate providers on the most effective uses of blood products or alternatively, treating the patient medically (i.e., using iron therapy in applicable patients as a first line therapy rather than transfusing the patient with red blood cells)

- Evaluating blood product utilization by individual provider

- Real-time intervention on blood orders that do not meet established transfusion criteria

- Asking providers to help justify possible unsubstantiated use of blood products

The use of electronic blood ordering and added layers of control, like clinical decision support (CDS) or a ‘best practices alert’ (BPA), may be the next growing trend to support a restrictive transfusion approach.5,1,7 Best practice alerts prompt providers to think about whether their orders meet transfusion criteria while they are placing an order. BPAs may include hard stops if a blood transfusion order has not met criteria, such as if the laboratory level (i.e., hemoglobin) at which transfusion is recommended is not met. These hard stops provide immediate feedback to the clinicians. For those institutions utilizing house staff or hospitalists to help manage hospitalized patients, follow-up reports provide feedback to attending physicians, who are ultimately responsible for treatment orders.2 Stanford University, for example, reported a 24% reduction in RBC transfusions once CDS was implemented.1 Studies show that a restrictive blood transfusion strategy also leads to equivalent, or better outcomes, such as a reduction in cardiac events, repeat bleeding, bacterial infection, and total mortality.10,11

Our program

Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center began an aggressive real-time blood utilization program in July 2016, which has been shown to be one effective approach to better blood utilization.12 Prior to initiating our utilization program, like many hospital transfusion services, the 355-bed nonprofit, academic medical center had an existing type-and-screen transfusion policy, shown to be effective in more efficient inventory management and, therefore, decreased blood product wastage.8 Without the benefit of clinical decision support, our transfusion service team members added the real-time program to actively screen blood transfusion orders to determine if established transfusion guidelines are met. The medical director of the transfusion service provides a phone consultation with the ordering provider each time a blood product is ordered for transfusion if the guidelines for transfusion criteria are not met. At the conclusion of the consultation, a recommendation to transfuse (or not) is made.

Our hospital uses the following transfusion guideline criteria for non-bleeding inpatients:

- Red Blood Cells: patient Hgb

- Platelets: patient platelet count <= 10,000/µL

- Plasma: patient INR >/= 1.6

At one-year post-implementation of this program, red blood cell utilization had decreased by 17%.

In addition to the real-time screening, we retrospectively review a report from our laboratory information system (LIS) each workday, which lists all blood transfusions, along with pre- and post-transfusion lab values (i.e., hemoglobin, INR, fibrinogen).

Finally, we gather monthly LIS reports on blood utilization sorted by physician, and the committee recommends which providers may need further review, and after further chart review, possibly asking the provider to write a letter justifying the reasons for transfusion.

In addition to our ongoing work to improve usage of RBCs for transfusion, we developed a formal study.

Our goals were to find out if:

- The trend of RBC transfusion reduction has continued to trend downward over a two-year study period compared with the six-month baseline.

- There had been a corresponding trend of increased inpatient iron therapy during the same timeframe.

- There had been a corresponding increase in utilization of laboratory anemia-related tests.

We collected data for the study from July 2016 to June 2018, comparing it to baseline data, which we collected from January 2016 to June 2016.

While improving transfusion medicine services was the primary goal, another benefit of this project and formal study may be an increased awareness about the roles of pathologists, pharmacists, and laboratorians in performing interdepartmental patient care. Care of the patient — with appropriate laboratory testing, iron therapy, and when necessary, RBC transfusions — may result in better outcomes and shorter lengths of stay.

In addition, during our program evolution, we have discovered that our pathology group is one of very few such groups in the U.S. currently billing a professional component for this important work in appropriate patient care.

Proper role of transfusions

Many studies and journal reviews in recent years note a focus on smarter blood utilization; that is, reserving the precious blood supply for patients who need it most, when other therapies have failed, rather than using blood transfusion as a first-line therapy to treat anemia in hospitalized patients. These studies and other efforts, like the Choosing Wisely program, have helped curb overutilization of laboratory testing and blood transfusions, leading to an overall decrease in blood collection in the U.S. and a concurrent decrease in demand for those products. There are some concerns that a negative result of this downward trend may be a more fragile blood supply. That could be a problem if the nation’s blood supply cannot meet temporary increases in demand, such as when disasters occur, resulting in numerous massive transfusions.

Study methods

We measured the total number of RBC transfusions monthly, gathering data from the LIS and capturing it in an Excel file. The total number of iron therapy patients was measured monthly by culling information from the pharmacy information system and capturing it in an Excel file. The total number of laboratory tests, including iron, retic count, and ferritin, were measured monthly from the LIS and captured in an Excel file. All data points (RBC usage, iron therapy usage, laboratory test data) were compared to baseline data in six-month increments, and overall.

We wanted to answer the following questions:

- Has iron therapy increased during the study period, compared to baseline?

- Have red blood-cell transfusions decreased during the study period, compared with baseline?

- Has the usage of anemia-related laboratory tests increased during the study period, compared with baseline?

Anticipated Complications

Complications of completing the study are limited to the resources available for data gathering and organizing. In addition, the hospital information system was upgraded in June 2018, which corresponded with the final month or our study. As such, pharmacy data for June 2018 was tallied from two separate computer systems: the legacy system for June 1-8 and the new system for June 9-30.

Conclusions

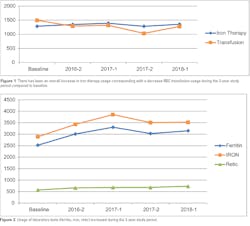

Our study data showed that iron therapy has increased on average 4.2%, compared to baseline. Blood utilization decreased 17%, compared to baseline, over the 2-year study period. (See Figure 1). In addition, there was an increase in medically related assessment of patients compared with baseline, over the 2-year study period.

All laboratory tests showed consistent increases in usage, with an average of 22.8% compared with baseline, when looking at all three tests: ferritin, iron, and retic count combined (see Figure 2).

Overall, our blood utilization program has been effective in both decreasing unnecessary transfusions and increasing use of laboratory testing that can help guide providers to possibly choose more effective treatment options for patients. In future studies, it may be valuable to look at patient length of stay and overall morbidity and mortality to better understand the relationships before and after implementation of a blood utilization program.

References:

- Goodnough LT, Shah N. The next chapter in patient blood management: real-time clinical decision support. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Dec;142(6):741-7. doi:10.1309/AJCP4W5CCFOZUJFU.

- Savage W. Implementing a blood utilization program to optimize transfusion practice. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:444-7. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.444.

- Shehata N, Forster A, Lawrence N, Rothwell DM, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A, et al. Changing trends in blood transfusion: an analysis of 244,013 hospitalizations. Transfusion. 2014 Oct;54(10 Pt 2):2631-9. doi:10.1111/trf.12644.

- Chung K, Basavaraju S, Mu Y, van Santen K, Haass K, Henry R, et al. Declining blood collection and utilization in the United States. Transfusion. 2016 Sep;56(9):2184-92. doi: 10.1111/trf.13644.

- Murphy MF, Goodnough LT. The scientific basis for patient blood management. Transfus Clin Biol. 2015 Aug;22(3):90-6. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2015.04.001.

- Wanderer JP, Rathmell JP. Perioperative transfusion: a complicated story. Anesthesiology. 2015 Jan;122(1):A23. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000457227.87496.c8.

- Goodnough LT, Maggio P, Hadhazy E, Shieh L, Hernandez-Boussard T, Khari P, et al. Restrictive blood transfusion practices are associated with improved patient outcomes. Transfusion. 2014 Oct;54(10 Pt 2):2753-9. doi:10.1111/trf.12723.

- Alghamdi S, Gonzalez B, Howard L, Zeichner S, LaPietra A, Rosen G, et al. Reducing blood utilization by implementation of a type-and-screentransfusion policy a single-institution experience. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Jun;141(6):892-5. doi: 10.1309/AJCPX69VENSKOTYW.

- Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, Danninger T, Mazumdar M, Opperer M, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349: g4829 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4829 (Published 12 August 2014).

- Bloch EM, Cohn C, Bruhn R, Hirschler N, Nguyen KA. A cross-sectional pilot study of blood utilization in 27 hospitals in Northern California. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Oct;142(4):498-505. doi: 10.1309/AJCP8WFIQ0JRCSIR.

- Salpeter SR, Buckley JS, Chatterjee S. Impact of more restrictive blood transfusion strategies on clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Med. 2014 Feb;127(2):124-131.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.017.Epub 2013 Oct 7. Review.

- Tuckfield A, Haeusler MN, Grigg AP, Metz J. Reduction of inappropriate use of blood products by prospective monitoring of transfusion request forms. Med J Aust. 1997 Nov 3;167(9):473-6. DOI: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb126674.x.