In the United States, workers work among the longest, most extreme, and most irregular hours; have no guarantee to paid sick days, paid vacation, or paid family leave; and pay more for health insurance, yet are sicker and more stressed out than workers in other advanced economies. U.S. companies fret about rising health care costs—health spending per capita in the U.S. increased nearly 29 fold in the past 40 years, outpacing the growth of the economy—and institute wellness programs like lunchtime yoga, meditation, anti-smoking, or obesity prevention.

But Jeffrey Pfeffer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, says companies are completely missing the point. Offering lunchtime yoga to stressed-out workers ignores the real reason why workers are so stressed out in the first place—management practices like long work hours, unpredictable schedules, toxic bosses, and after-hours emails. It’s not individual workers making bad choices about their health that’s making them so sick. It’s the way corporate America expects workers to work. And in his new book, Dying for a Paycheck, he argues that the costs have become so great that it’s time for companies and the government to take responsibility and create real change.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Brigid Schulte: In your new book, you maintain that the workplace has become “shockingly inhumane” for everyone—white-collar workers, blue-collar workers, low-wage workers, managers. How so?

Jeffrey Pfeffer: My colleagues and I looked at 10 different workplace exposures and their effects on health—things like economic insecurity, work-family conflict, long work hours, absence of job control. We found that they account for about 120,000 excess deaths a year in the United States, which would make the workplace the fifth leading cause of death and costs about $190 billion dollars in excess health costs a year. So many of these workplace practices, like work-family conflict and long work hours, are as harmful to health as secondhand smoke, a known and regulated carcinogen. I chose the title of the book intentionally. We are literally killing people. People are dying for a paycheck. And I think it’s unconscionable.

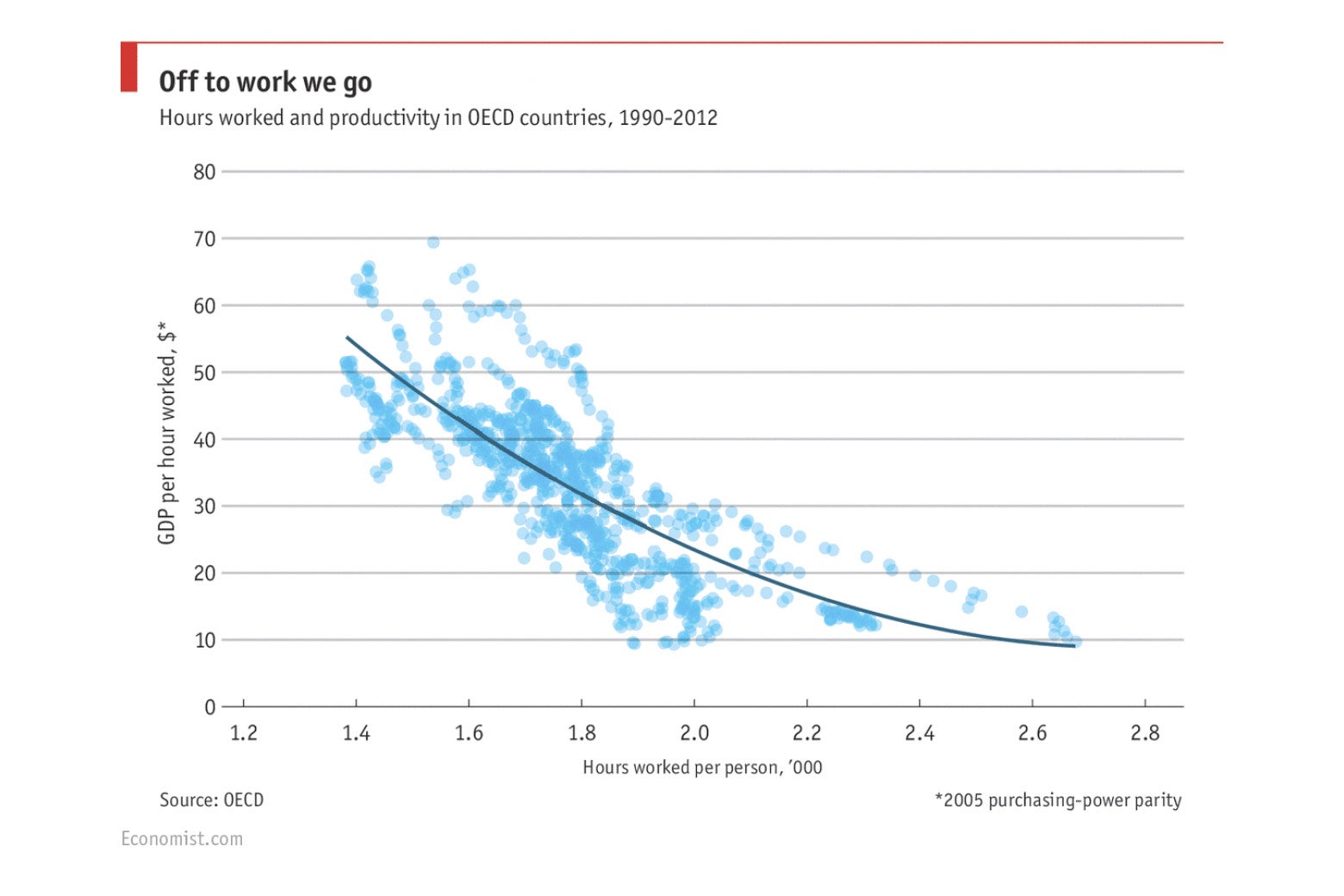

We found that workplaces are a source of the health crisis, which is being observed all over the world, as health care costs are rising. The irony is, of course, that most of what we’re doing at work that’s making people physically and mentally ill is also not helping companies or economic systems. The Economist magazine ran this interesting chart in which they show productivity on one axis and work hours on the other. There’s this nice linear negative relationship—the more hours a country’s working, the lower the productivity.

These studies have been done at the industry level as well and show the same thing. So the idea that you’ve got to work all these crazy hours in order to be productive is just not true. It’s completely empirically incorrect. Same with layoffs. They don’t benefit companies. Job control and micromanaging doesn’t benefit companies. So we’ve created a lose-lose situation in which people are suffering and companies aren’t benefiting. It’s just pretty bad.

Why would we foster work systems that both punish workers and lose companies money? What you’re describing sounds irrational.

That’s correct. Companies know that their health claims are going up. And the next sentence is, “What are you going to do about it? Your health is your responsibility not mine.” We have created the world’s most toxic environment for which we take no responsibility.

In the U.K., the government began to look at work practices and health in much the same way that other countries look at and control environmental pollution. Because when you dump your stuff into the air and water and somebody else pays to clean it up—you’ve externalized the costs. The government in the United Kingdom began measuring lost work time and the cost of stress and began to ask, “Why should we be paying to clean up the health mess that you’re creating by the way you treat your workforce?” The Health and Safety Executive, which is the UK’s equivalent to OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] in the United States, recently reported that in 2016–17, 12.5 million workdays were lost due to workplace stress, anxiety, and depression. So this is economically significant. Other governments are beginning to look at this, and sooner or later, I think they’re going to say to businesses, “You cannot just pass these costs off onto the larger society.”

You cite surveys that show high levels of worker disengagement, presenteeism, distrust of management, and burnout, and one that found 7 percent of workers were actually hospitalized because of workplace stress. How did our work environments get this bad for everyone?

It’s been getting worse gradually over time. Forty, 50, 60 years ago, layoffs used to be a response to economic downturns. Now, when [Brazilian private equity group] 3G Capital engineers the merger between Heinz and Kraft and lays off 20 percent of the workforce, it’s seen as a routine part of economic life. But the evidence suggests that suicide rates more than double for people who were laid off, that heart attacks go up 40 percent, according to one study. And studies show downsizing does not positively affect economic performance.

We’ve also seen a rise in scheduling software and the “just in time” workforce for managers who don’t want to add any extra people on the retail floor or in banks, ostensibly to save labor costs. But that kind of scheduling is quite stressful for workers, because you don’t know what your work hours and therefore what your income is going to be from one week to the next. You don’t know very far in advance when you’re going to be working, so that makes it hard to plan for your other family obligations.

Work hours have gradually increased over time, as has the idea, with technology, that you should be always “on.” You know, it’s funny, most of the people who check their email off hours—81 percent of people according to one survey do—these are not emergency-room physicians. There’s actually there’s nothing going on that requires you to be on. But people think they need or are expected to be. People are not taking vacation in the United States. It’s unbelievable that 25 percent of workers don’t get any paid time off. Workers are going to work sick. Forty, 50 years ago, CEOs saw themselves as balancing the interests of employees and customers and shareholders and the community. And now it’s all just about the shareholders.

But honestly, when you look at working conditions throughout history, they’ve always been pretty awful for just about everyone but those at the top. Think about coal miners and black lung. Serfs in medieval times. Could you argue, cynically, that this is just the way of work?

Well, we did abolish slavery, and we did abolish child labor, though they were economically profitable. OSHA has, over the years, really made the physical aspects of work substantially safer so that there are not as many people dying in workplace accidents on construction sites or on oil rigs. We’ve cleaned up a lot of the physical aspects of work. But we have not cleaned up the psychosocial aspects of work. When people moan about excessive health care costs, I say you better start at the workplace, because if you don’t fix what’s going on in the workplace, we will never fix health care costs.

You have five recommendations for the way forward in your book: measuring health and well-being, calling out what you call the “social pollution” of these toxic work practices, implementing policies that reflect the true cost of management decisions, confronting the truth of difficult trade-offs between employer profits and employee health, and insisting that business and political leaders prioritize human sustainability.

I think change is going to take a while. It may take some kind of social movement, or maybe litigation. But the lesson from the quality movement and the lesson from management in general is that what we don’t measure we’re never going to get better at. So companies should be measuring what their workplace practice effects are on their employees. If you’re a self-insured employer, go to your benefits administrator and ask for data on employees use of antidepressants, sleeping pills, ADHD, drug use, medical claims. Just as studies were done to measure the effects of CEOs on productivity in the auto industry years ago by some colleagues of mine, you could measure the effect of CEOs on drug use. We ought to measure this and hold people accountable.

I also believe that people need to begin choosing their jobs carefully and stop rationalizing, “Well you know I’m only going to do it for a short time,” or “I’m young, it won’t affect me,” Or “I can put up with this, I’m tough.” For the last 40 years, human resources departments in their policy manuals say you are responsible for your own health. So you have to take responsibility for your own well-being.

But isn’t that too much to ask of individual workers? To put the onus on them to change the system?

It may be. I understand it’s a hard thing to ask, but it’s pretty clear that most organizations have, for the most part, abdicated their responsibility.

Workers with education and resources may have more ability to change the way they work or the choice to leave toxic work environments. What about workers who don’t?

They’re in even worse shape. In the last two years, average life expectancy in the United States has gone down and health inequalities are rising. People with less education have less access to health insurance. They are much less likely to have job control and are much more likely to face economic insecurity, which increases stress. It’s one of the reasons why we have these enormous health disparities. And the only thing that’s going to fix it is a policy that says, “We are tired of this, this is unacceptable, and there is a level we should not fall below.” Already, the discrepancy between the counties in the United States with the highest and lowest life expectancies is 20 years. Twenty years!

You end your book with a conversation with a nun about how this is really all about what we value as a society. In other words, what is work for? And how can we keep it from crowding out the rest of life, like time for families, health, even leisure?

My friend, Nuria Chinchilla, a business professor in Barcelona, says, “You live in a country where everybody talks about valuing life. Yet what they only seem to care about is just the beginning and the end of life, not the middle.” That’s exactly correct. At the end of the day, we ought to value human life, value not just environmental but human sustainability. More people need to have a sense of stewardship over the lives of their employees, who’ve placed their well-being in leaders’ hands, and take that responsibility seriously. The worst thing about this is that I don’t think anybody cares. And on the day we start caring, we’ll do something. Until then, nothing is going to happen.