Today’s post is by author Wendy Lyons Sunshine.

Just as mountain climbers need a sturdy harness and strong rope to reach the summit, writers depend on robust digital tools to carry us through to a book deadline.

For my latest book, I wanted tools that would let me efficiently juggle a great deal of content and citations. The first choice for my toolkit was Zotero, a citation manager that lets you grab information with a single click of a browser extension, conveniently links text, notes, and tags to the citations, and outputs formatted citations with a few clicks.

But settling on a word processing choice was trickier.

My wish list

I spent a few years as a technical writer, hammering out data-heavy documents and ushering them through multiple revision and output cycles. When you’re elbow deep in hundreds of pages, continually moving graphics, tables, and chunks of data, the last thing you want is to format, mouse, scroll, or cut and paste more than necessary. The right tool offers shortcuts and flexibility. Our group relied on specialized software called FrameMaker to boost efficiency and maintain quality.

For my own book, I imagined a tool that could likewise weave together varied content: personal narrative, as-told-to stories, case studies, heavily cited exposition, and graphics. At minimum I wanted:

- Auto-generated outlines

- To easily jump forward or back among chapters and sections

- To easily reorganize material in a modular manner, using high-level drag-and-drop (like cut and paste, but on steroids).

Fortunately, the first two capabilities are easy to find. Google Docs and Microsoft Word, for example, both support heading styles and outlining capabilities. My wish for the third capability got me flirting with Scrivener.

Scrivener’s allure

Professional writer colleagues rave about Scrivener’s drag-and-drop flexibility, and I felt compelled to give it a look. After a tutorial, I noodled around with a dummy draft. Scrivener’s “bulletin board” with “notecards” did appear to be a powerful organizational tool, making it easy to focus passages and rearrange content.

What daunted me, however, was how to output a draft and incorporate revisions. From what I could deduce, Scrivener outputs to standard formats, but real editing must be done within Scrivener. That meant any changes that I or someone else marked on a draft (output to Word, for example) had to be input into Scrivener, instead of just accepted into the document. Perhaps I missed something buried in Scrivener’s menus, but I couldn’t see any way to easily and productively collaborate on drafts with my editor.

Stumped, I took a fresh look at Word. Could it be coaxed to approximate Scrivener’s powerful visual and modular drag-and-drop feature?

Ultimately, yes. The trick is inserting many descriptive, often temporary, headings in combination with Word’s styles and navigation pane. Here’s how it works:

Getting Word to behave more like Scrivener

Insert descriptive headings throughout the manuscript. You might insert a heading above each:

- Chapter

- Section

- Scene

- Figure or illustration

- Sidebar

- Any unit of content that needs to be easily identified or moved.

The goal is to clearly identify where a chunk of content begins. By default, that chunk ends where the next chunk (denoted by a heading of the same level) begins.

Assign styles

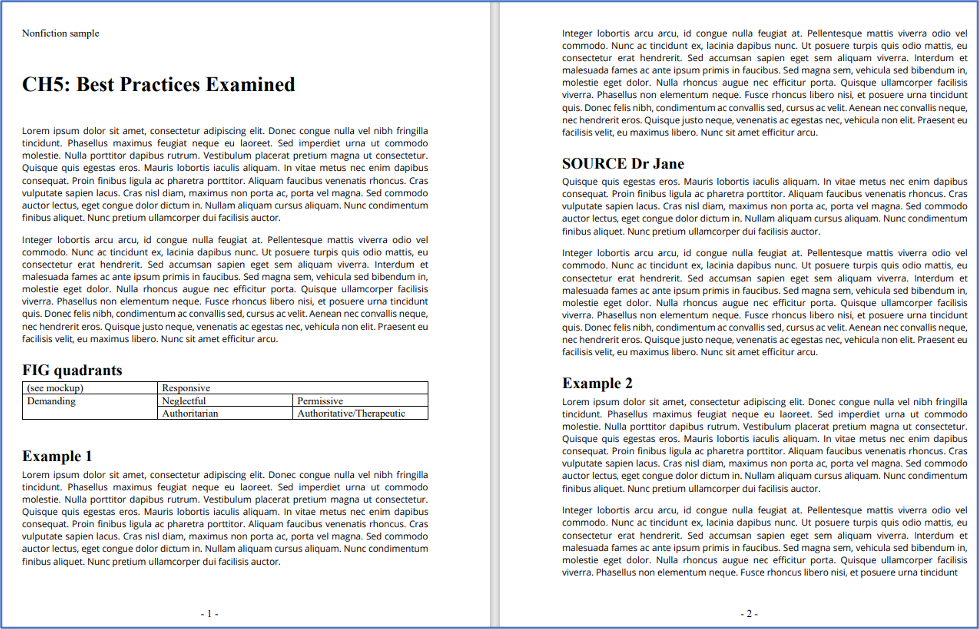

Open Word “Styles” and assign each of the descriptive headings a standardized heading style. Assign “heading 1” style to chapter titles, then assign “heading 2” to other types of content. (This keeps the hierarchy as flat as possible to begin; more levels can be added later, after you get the hang of it.) Here’s an example of a nonfiction manuscript set up this way:

Open the Navigation Pane

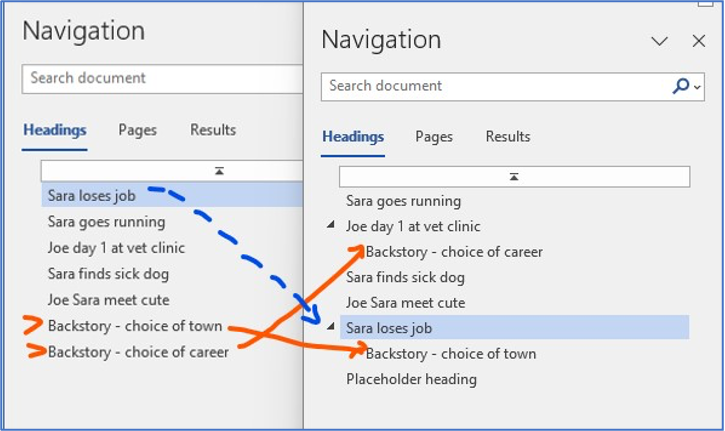

Now that headings are set up, open the navigation pane via View > Show > Navigation Pane. The Navigation Pane will display vertically along the left of the screen. For the sample pages above, it would look like this:

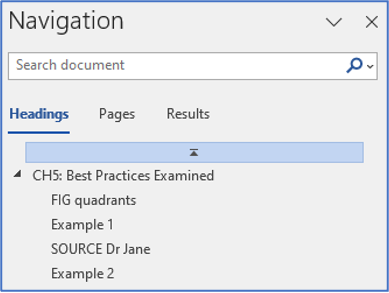

Use the Navigation Pane two ways. First, you can navigate to specific content by clicking on that specific heading. Second, and most wonderfully, you can reorganize content by dragging and dropping the headings. Navigation Pane headings behave much like Scrivener’s index cards and are easily shuffled around.

Dragging a heading moves all associated content together in one bundle. This works beautifully across a large document and is far easier than trying to cut/paste/or drag blocks many pages apart.

Craft headings strategically

By crafting brief, standardized headings, you’ll make it easy to scan and browse the Navigation Pane. I sometimes use ALL CAPS to make certain information more prominent.

That’s why in the sample shown above, chapter is shortened to CH#. This leaves room to see more of the full title in the pane and also to scan visually for chapters across the entire book. Source interviews are <SOURCE – name>, and graphic elements are identified as <FIG – descriptor>.

For fiction

Fiction writers can adjust this approach for their needs by crafting headings to describe POV, scene, location, interiority, backstory, etc.

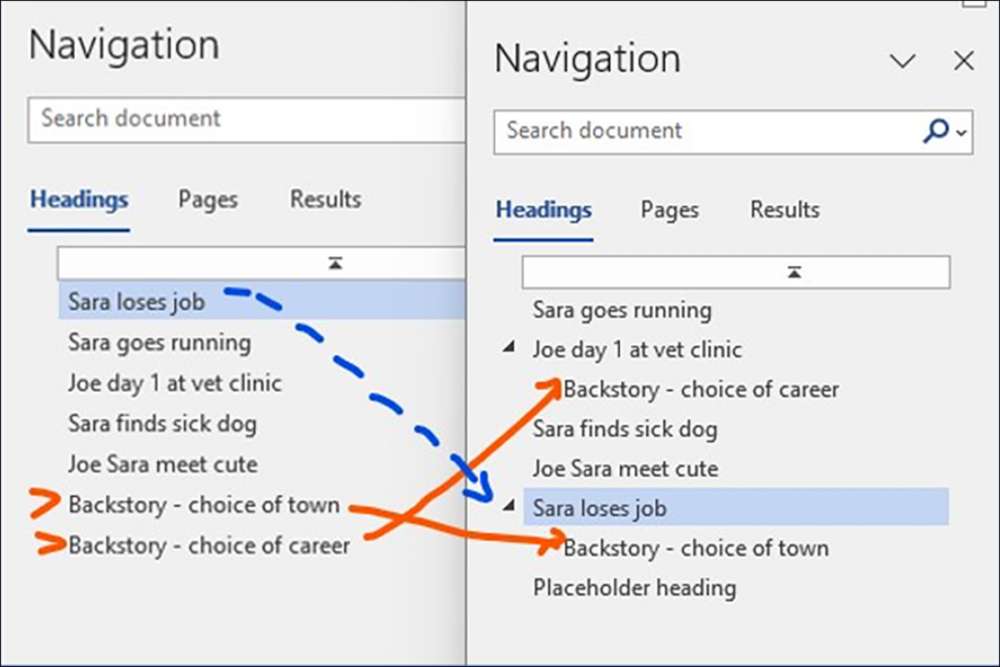

Below, on the left, is an imaginary raw fiction manuscript set up this way. On the right, content has been dragged and dropped into an alternate sequence using the Navigation Pane. Notice that on the right, backstory segments were nested or “demoted” by changing from Heading 2 to Heading 3.

Getting creative

At one point during my book’s evolution, I wanted to keep an eye on word counts. The Navigation Pane helped there, too. First, I checked a chapter’s word count, then embedded that total into the heading format of <word count – chapter number – name>, such as “750 CH8 Attunement” or “5000 CH2 Science of Family.” Then I could scan for chapters that were complete versus those that needed more content.

Last steps

When the draft was ready for final production, all I had to do was strip out superfluous headings and replace abbreviations with the full spelling.

Despite the extra effort of inserting headings and stripping them out later, this strategy was a huge help. It allowed me to play with my book’s structure and track where I had located case studies, visuals, and so on. It reduced scrolling and prevented messy cut and paste errors. As a final bonus, I didn’t have to master new software while under deadline pressure!

Final note: If you run into trouble, double check Word’s advanced settings to make sure that drag and drop is enabled via: File > More… > Options > Advanced > Allow text to be dragged and dropped.

Wendy Lyons Sunshine is an award-winning journalist and author of Tender Paws: How Science-Based Parenting Can Transform Our Relationship with Dogs, published by HCI/Recorded Books. Tender Paws grew out of Wendy’s collaboration with leading child welfare experts on two books, including the classic bestseller, The Connected Child: Bring hope and healing to your adoptive family.

Good thoughts — there’s a lot of structural information you can set up in Word that way.

I take a different approach, because I like keyboard shortcuts and jumping around as fast as possible. So I use Word’s Find/Replace tool to search for Formatting: Centered, which means that once I’ve run that search once, each tap of Control-PageDown moves me ahead to my next scene break (with its centered asterisks) or chapter heading.

Thank you for this! I’d not played around enough with the different heading styles. I use this for my outline document. Under each chapter/scene title, I note the changes or ideas I want to incorporate in the story document.

Also, I like to have the outline’s main doc open as table of content. Through the paragraph arrow, I can checkmark the box so titles stay “collapsed” by default. This is helpful for my outline where I highlight the headings: blue = good to go, green = need to grow, etc and I can see at a zoomed out glance how the story is progressing.

Excellent! This is the way I always work in Word, making full use of styles and references. I also use this to format chapters.

I came across the utility of nav pane almost by accident, but your tips for making it more useful will fix some of the problems I’ve run into. I’ve also used it for organizing research. My primary source is a colonial newspaper, and I copy the transcriptions into Word with date of publication as the heading so I can look at nav pane and find what the newspaper was saying around the events I’m writing about.

I wish I’d know this when editing my non-fiction, instead of the clunky cut-and-paste moving I did! But I’m definitely going to add these tips into my fantasy MS. Thank you for making it easier!

Wendy — Another problem you may not have gotten to with Scrivener is that it doesn’t play nice with Zotero, as I found out when writing my book, especially after exporting to Word (and then having to reimport).

I loved Scrivener for its many other tools and features, especially its ability to organize, categorize and retrieve material. The outlining and cork board features, IMHO, are still more intuitive than the method you suggested in Word. I liked Scrivener enough to craft my “final” draft, which turned out to be the first of many, many “final” drafts.

At some point, it felt more comfortable revising (with editor’s notes) in Word, which plays beautifully with Zotero and automatically generates TOCs in several format.

Mel – that’s interesting. How do you integrate Zotero with Word?

I didn’t even try to attempt that learning curve, because my publisher does not accept automated endnotes. They required numbering in the text manually inserted as superscripts, starting at “1” for each chapter.

I decided to keep this process simple and hold off on cite numbering until the very end. Instead, I flagged each referenced spot manually by bracketing [author/date/etc] so that the cite info would travel along with the moveable text blocks, while I rearranged as explained in the article.

Once the overall ms. structure was super-solid, and the ms. was ready for final review, then based on the bracketed details I put in superscript numbers, created a separate endnote file of citations (which later got appended to the ms.), and stripped out the bracketed info. Thank goodness for Zotero keeping all the citation info neat and safe outside the ms. I’m curious what further Zotero efficiency I may have missed!

Wendy — Apologies. had no idea you replied to my reply. I didn’t get an email notification.

Zotero has been adopted by many colleges and universities, some even offer YouTube instructions. I’m not sure what your publisher’s issues are…except that if a book publisher hasn’t entered all the required meta data correctly, it’s a situation of garbage in, garbage out. Book publishers are pretty good, but publishers of, for example, documentary videos or audio or older books…not so much.

Zotero is stupidly easy to use with Word.

Open Zotero. Click on “Zotero” in upper left corner of your screen. Zotero–>Settings–> click on ‘cite’ icon at top if not selected–>click on word processors. Install Word add-on.

If it’s installed correctly, on the top menu line in Word you’ll see ‘zotero’. You may have to make the extension ‘visible’ on the menu line.

1. Zotero will prompt you select the style of citation you desire; most US publishers use Chicago Manual of Style, and Zotero has three variations.

2. In Word, put your cursor where you want to insert the citation, click on Zotero and select the book/source you’ve collected in your Zotero library. You may need to add a page number or other missing data. Play around with it; it’s very easy. BTW, I prefer the “classic” view because it gives me options. You make this the default by clicking on it in the same “Word Processors” window from which you installed the Word add-on.

3. In Word, (not Zotero) you select whether you want the citations to be footnotes (on the bottom of the page) or endnotes by chapter or document. [For my book, an investigative memoir, not an academic text, I did not want the superscript numerals to appear. Like many modern memoirs, I wanted the citations in the back of the book, listed by chapter and page number. This took a lot of manual labor.]

4. The nice thing is, if you insert or delete or move a footnote later, it adjusts the numbering. Even if you add a footnote manually via Word’s built in function, the numbers adjust themselves.

5. But reimporting the document into Scrivener kills this dynamic ability – the footnotes become static, just so much text.

Hope that helps. Feel free to email mail me directly if you have questions.

Mel

Thanks so much, Mel. I’ll have to play around with that connectivity. Thanks for demystifying it!

Wendy

I love this! I can’t wait to try this out even with shorter form work to give me that zoom up look and perhaps move around attempts in a series .

I embed descriptive outline information at one level below chapter headings and *** scene breaks, then make that text invisible. It shows up in outline view (I have very old Word) and allows me to swap chunks easily. I even keep short outlines and notes for each scene. Then before publishing to PDF I just Find all invisible text and replace it with nothing.

Very clever. Thank you

I agree; this is a great use of headings and the navigation pane, especially for nonfiction. But even for fiction, I personally have started adding extra information to the chapter headings, such as which pov the chapter is in and how many pages the chapter is. Occasionally also a few words about an important event in that chapter. This all stays visible in the navigation pane, which is helpful all the time, but especially during revision.

But for nonfiction, this feature is absolutely priceless for reordering sections and chapters!