Almost half of rape victims are dropping out of investigations, as a growing proportion do not want to pursue a prosecution even when a suspect has been identified, according to a Cabinet Office report leaked to the Guardian.

The figures, which were prepared for a secret internal government review earlier this year, reveal a system in crisis as tens of thousands of women are reluctant to pursue their alleged attackers when faced with invasive disclosure demands, a lower likelihood of securing a conviction and lengthy delays in seeing their case brought to court.

The report, which has emerged during an election campaign in which the Conservatives are making fighting crime a central tenet of their election strategy, suggests a lack of resources, owing to austerity, is impacting the criminal justice system’s ability to pursue rape cases.

Reported rapes are on the rise. However, police are referring fewer cases to the Crown Prosecution Service, which in turn is prosecuting even fewer cases.

The highly sensitive data was assembled earlier this year by the prime minister’s implementation unit as part of an urgent investigation into the dramatic fall in rape prosecutions in England and Wales. Rape prosecutions are at their lowest level in more than a decade.

The briefing shows senior civil servants acknowledging the way the criminal justice system deals with crimes “is particularly poor for rape” and expressing suspicions – never publicly aired – that problems may be due to lack of resources.

The document, marked as “official – sensitive”, notes: “Police are assigning certain unsuccessful outcomes after shorter investigations than in previous years.” It also says: “The drivers for this are unclear, but it may be indicative of ‘rationing’ of police time and resources to more ‘solvable’ cases.”

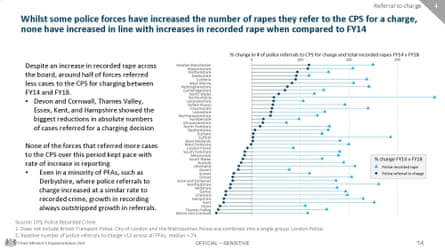

While recorded rapes increased by 173% between 2014 and 2018, the police referred 19% fewer cases for charging decisions and CPS decisions to prosecute fell by 44% in the same period.

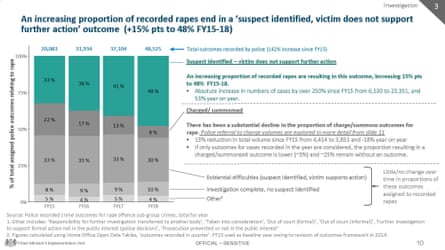

One of the most concerning changes is the growing proportion of cases resulting in “outcome 16”, whereby a suspect has been identified after a police investigation but the victim does not support further action. The document reveals that from 2015 to 2018, the proportion of cases dropped owing to an outcome 16 rose from 33% to 48%.

Last year, more than 20,000 women – an average of one every 30 minutes – decided not to proceed with a rape investigation, even when the suspect had been identified.

Campaigners believe the sharp rise may reflect victims being discouraged from pursuing complaints because they face disclosure of their intimate, private life through requests for the contents of their phones and laptops. The sheer length of time from offence to completion at court, which has increased by 37% to an average of two years since 2014, may be deterring others.

Claire Waxman, who is London’s first victims’ commissioner, said the figures highlighted significant problems in the way the criminal justice system deals with rape. “There is such inconsistency between police forces and areas over the way they handle rapes,” she said.

Q&AWhy do the police want rape victims' phones?

Show

Police guidance states that when investigating a crime: "Mobile phones and other digital devices such as laptop computers, tablets and smart watches can provide important relevant information and help us investigate what happened. This may include the police looking at messages, photographs, emails and social media accounts stored on your device."

In investigating rape or sexual assault, the police my use that data to verify where a victim was at the time of assault, and if they had prior contact with the suspect. They are also obliged to disclose evidence to the suspect's defence teams. Defence lawyers have accused police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) of failing to hand over crucial digital evidence in rape and assault cases that would have exonerated their clients.

Victims of rape and serious sexual assault who refuse to give police access to their mobile phone contents have been told they could allow suspects to avoid charges, and cases have been dropped.

There is an underlying problem for police in the sheer volume of text, video and call records now available in even routine cases, and particularly in domestic abuse or sexual assault allegations involving people who already know each other - and this has been a factor in the sharp drop in the number of cases reaching court.

“We did a survey in London with the Met of 500 cases and found that in 58% of them victims withdrew complaints. The main reason we are seeing that is [threats] to privacy from disclosure. People feel very pressured to consent. Victims don’t want to share all their personal details even if it’s only with the CPS and police. It’s a risk they don’t want to take.”

The report also reveals regional variations in accessing justice for rape victims. Figures show not a single police force in England and Wales has referred cases in line with the increases in recorded rape between 2014 and 2018.

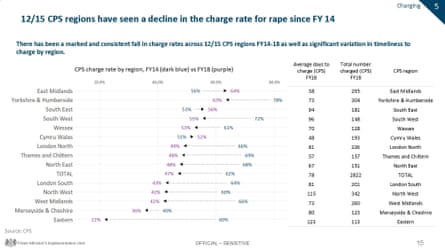

The lower number of cases referred to the CPS has been compounded by a further decline in the charging rate. The majority of CPS areas showed a decline in the charge rate for rape between 2014 and 2018. Overall 11 of 14 CPS areas showed significant falls in the rate of charging suspects and three – Wales, the south-east and east Midlands – showed increases. This effectively results in further variation in a victims’ chances of seeing their case prosecuted.

The review also shows the amount of time taken by the CPS to produce a decision on whether or not to charge a suspect has doubled since 2013-14, when it was on average 30.6 days, to 2018 when it reached 86.2 days.

Katie Russell, a spokesperson for Rape Crisis England & Wales, said: “The criminal justice process takes far too long and can be re-traumatising for those who’ve already been subjected to the trauma of sexual violence or abuse.

“There are wide disparities in the way sexual offences are handled in different areas. And perhaps most alarmingly, charging rates are declining despite numbers of reports to the police being at an all-time high. The bottom line is that only a tiny fraction of sexual offenders are being brought to justice and victims and survivors of these serious crimes are being failed.”

A legal challenge has been launched against the CPS over its failure to pursue rape cases after a collapse in rape charges. The challenge follows reporting of allegations by the Guardian that prosecutors have been advised to “take the weak cases out of the system”, prompting concerns of a undeclared change in its approach to prosecution.

A CPS spokesperson said: “The growing gap between the number of rapes recorded, and the number of cases going to court is a cause of concern for all of us in the criminal justice system. We consider every case referred to us by the police and the CPS will seek to charge and robustly prosecute whenever the legal test is met.

“Most CPS Area teams deal with multiple police forces and any variation in referral numbers will lead to differing charging rates. The cross-government review will explore the issue of regional variation and we are working with police to continue to improve how we manage these complex cases.”

The 24-page long “end-to-end review of the criminal justice system’s response to rape” was circulated among cabinet, senior civil servants, senior police officers, prosecutors and victims’ groups involved in the review, which is being coordinated by the Criminal Justice Board. The CJB is chaired by the justice secretary, now Robert Buckland QC, and brings together the home secretary, currently Priti Patel, law enforcement agencies and the senior judiciary.

Sarah Crew, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) lead for adult sex offences, said: “Everyone with a role in investigating and prosecuting these crimes acknowledges there is more to be done in increasing the number of cases brought before the courts.

“Once we understand what is causing these trends, we and our partners are committed to making real and lasting improvements across the whole system.”