The Hidden Cost of a Flexible Job

It's nice to be able to work from home once in a while, but workers wind up compensating with longer, more intense hours.

It's freezing and snowy. It's a million degrees and humid. Your kids are sick. The repairman is coming. You have a doctor's appointment.

Whatever the reason, many workers are lucky enough to be able to take advantage of workplaces that offer a bit of flexibility as to when and where they work.

But such affordances come with strings attached: Employees with this perk often wind up working extra hours at nights or on weekends. Why? Not to make up for lost productivity (studies show that workers are just as diligent if not more so when working from home) but in an effort to demonstrate their commitment to and passion for their jobs.

Researchers call the phenomenon "the flexibility stigma."

"In high-level, professional jobs, [the stigma] stems from what one sociologist called 'the norm of work devotion,' where you have to prove yourself worthy of your job by making it the central focus of your life—the uncontested central focus of your life," says Joan C. Williams, director of the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law. For employees who occasionally would like to work from home, that means working ever harder and ever crazier hours, lest anyone think their jobs were anything but their top priority.

Women with children may be the most likely to take advantage of an employer's flexibility, and thus may experience the stigma most often, but Williams says that it hurts everybody—"everybody who is not a breadwinner married to a homemaker," because those lucky few are the only people who can realistically comply with "the norm of work devotion." Men, women, those with kids, those without—everyone who deviates from the "ideal-worker norm" will need to demonstrate their devotion in other ways. "It's equal-opportunity misery," says Williams.

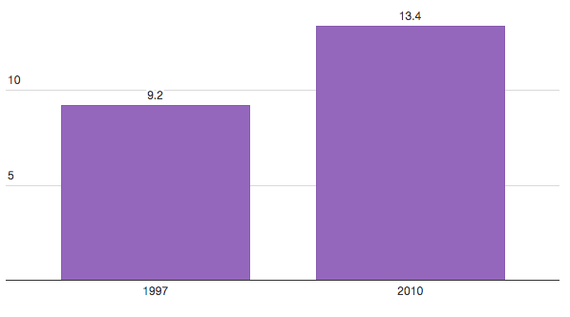

Over the past two decades, increasingly sophisticated technology has meant that fewer and fewer people need to be in the office to get their work done. Between 1997 and 2010, the number of Americans who work from home at least one day per week rose by 4.2 million. As a percent of the total workforce, this is a jump of a bit more than two percentage points, from 7 to 9.4 percent.

Most of those workers—9.4 million—are people who work from home entirely. But a good chunk—4 million people—are what the Census Bureau terms "mixed": They have an office job, but they also work from home on occasion. These mixed workers are a special bunch. They are highly educated: Of "flexible workers," 63.3 percent have a bachelor's degree or higher, compared with 50.5 percent of those who work solely at home and 29.7 percent of those who work solely on site. They are better compensated, bringing home an average earnings of $52,800 a year, compared with $25,500 for those who work at home and $30,000 for those who work on site. And they work harder, putting in more than the 40 hours that's standard for other workers.

Why does this high bar persist? It's not because it makes business sense: Overworked workers are less productive. It's because, Williams says, those who have succeeded in this system don't want to see it any other way.

"One of the reasons that this [culture] has proved so unbelievably difficult to change is that the winners of the system are the breadwinners who saw very little of their children," she explains. "It's an identity-threat situation; they have an incredible amount invested in proving that's the only way to be a professional. Because, if it isn't, why did they do it? How come they don't know their children?"

It wasn't always this way. Once upon a time, the limitations of technology set a firmer boundary between work and home: If you weren't at the office, you often couldn't do your job. But that's no longer the case.

"Technology now sets no work boundaries," Williams says. "So we have to set these work boundaries through social norms."

The only problem, she says, is that we aren't doing that.

"I've been working on this problem for 25 years, and I actually have come to the conclusion that these organizations just aren't going to change."