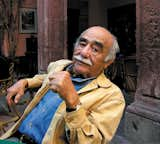

An Interview With Frank Lloyd Wright’s Photographer Pedro E. Guerrero

Editor's note: Pedro Guerrero passed away in 2012.

Though Guerrero’s 60-plus-year career as a photographer is underscored by his work with Wright, he enjoyed later success shooting interiors for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and House & Garden, in addition to forming close friendships with artists like Alexander Calder and Louise Nevelson. At 90, Guerrero is experiencing a renaissance of sorts, with the recent release of both a documentary film and a memoir. Dwell traveled to Florence, Arizona, to spend some time with the photographer, who proves to be a sublime storyteller—with or without the camera.

Which came first, photography or architecture?

Neither, actually. I had gone to Art Center School [now the Art Center College of Design] in Los Angeles, thinking that I would become an artist. I was trying to escape the bigotry of my hometown, Mesa, Arizona, and I thought being an artist would be exotic. But when I got there, all the art courses were filled. I asked them what else they taught, and they said photography. I had never thought of photography before. But I would have taken embroidery rather than go back to Mesa.

So how did that lead to photographing buildings?

I had seen an exhibition in 1938 or 1939, and one of the photographs that struck me was that of a distinguished gentleman. As it turned out, it was Frank Lloyd Wright, whom I knew very little about. But about ten photographs down the aisle, I ran into one of the most spectacular photographs I had seen—it was of Fallingwater.

Frank Lloyd Wright at the Reisley House in Usonia, a cooperative housing development in Pleasantville, New York, 1952.

Did that encourage you to pursue a job with Wright?

I had the beginnings of what might be considered a profession, but I hadn’t decided yet what I was going to do with it. My dad suggested that I go see Frank Lloyd Wright’s school in the desert to see if maybe he had a role for a photographer. So, on a day of unimagined importance to me, I took off for Scottsdale and aimed my car for this white slash against the mountain that I thought was Taliesin West. When I got there, I saw this man that I had seen in the photograph. He looked at me and said, "And who are you?" I told him that I was Pedro Guerrero, and that I was a photographer. And he said, "Well, come and show me what you’ve done." I wouldn’t have gone up there if I’d known even a little bit about him. My samples were ridiculous: some Japanese fishermen on the wharf at San Pedro, some nudes. Every once in a while Mr. Wright smiled and even chuckled, but when he came to the nudes he said, "I see you have a fondness for the ladies." He said, "The pay isn’t much, but you could live here and you could use my camera if you want to." I found out the pay wasn’t anything, but it didn’t matter.

Without any experience with architecture, how did you approach shooting his work?

I took it to be sculpture—sculpture of stone and cement, canvas, and wood. I was intrigued by the fact that there were a lot of young men working, and I found that they were wonderful subjects to photograph.

How did Wright react to those first shots?

At the end of a couple of weeks, I took what I had done to him, and he was very pleased. I spent two or three months shooting there.

Alfie Bush was one of the many young apprentices who helped build "the Camp," as Taliesin West was then called. Here he’s shown working on the dining hall.

You were just 22 at the time and inexperienced. Why do you suppose Wright responded to you so well?

For one thing, it was just pure luck. Just before I came to show Mr. Wright my portfolio, the man who had been his photographer eloped with one of the female apprentices. So, my timing couldn’t have been better. But after I started showing him what I could do, and when I told him that I didn’t know anything about architecture, he said, "Well, I’ll teach you." He’d say, "I want a photo of architecture, I want to see it from terminus to terminus, or at least give me a connection from one part of the building to another so that I can see that it’s my building." Today, there are a lot of people doing [detailed] photographs of Mr. Wright’s, which he would have hated.

Why?

He wanted to see as much of the architecture as he could in one shot, and I wanted the same thing. There were very few instances when I took his elements and made a composition for myself. Outside of that we got along fine.

His very particular aesthetic must have permeated your work, especially since you were so young.

Except for the two years I went to art school, there was a lot left out of my education that I had to get from other people. I tried to rid myself of any of the habits I had formed as a young Mexican-American trying to fit in to an Anglo society. I was absolutely entranced with the fact that Mr. Wright was very minimal with his architecture. His own home was filled with things he loved, but when he went with me to do a home, like the Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin, he went around and told me which pictures to take down because it took away from his architecture. He wanted everything to reflect his design and his taste.

"When I set up this shot of Wright in his studio at Taliesin, he hadn’t shaved that morning and told me he wasn’t about to. So I had to move the camera back to conceal the stubble, which actually improved the shot." Behind Wright is a model of the San Francisco Call building, a favorite of his that was never built.

You spent a lot of time with the forefathers of mid-century modernism, living in New Canaan, Connecticut. Did you work with any of them?

I knew Marcel Breuer, Ed Stone, Eliot Noyes, Joe Salerno, Landis Gores, Jens Risom, Victor Christ-Janer. They were all likeable guys doing their own version of the modern style, but I didn’t try to get work from them, probably out of misplaced loyalty to Mr. Wright. I photographed their architecture only if I had an assignment from a magazine.

Architect John Black Lee’s Day House, in New Canaan, Connecticut, 1966. "After Calder built a new studio and home near Sache, France, he sent me a postcard that read: ‘We have a new shack. We’ll be seeing you.’ I took it as an invitation and went to visit in 1964."

What do you think of modern architecture today?

I was never really a champion of modernism until much later, when I realized that they did have a message; their stuff was built with a basic philosophy just like Mr. Wright’s organic architecture. But compared to the architecture now, I wish I’d spent all my waking moments with them. I suppose the reason [mid-century modernism is] appreciated now is because what’s new is absolutely deplorable.

What was it like living off your photography? I can’t imagine it paid very well.

You’re absolutely right about that. I remember my father-in-law came to visit us in New Canaan, and he looked over my income and said, "You could do better as a stock boy at one of the grocery stores."

Did you face much discrimination as a Latino?

After the war, one of the first organizations I went to to look for work was MoMA because I knew the architectural director. She told me that when the show on Frank Lloyd Wright’s work opened at MoMA in 1940, several of my photographs had been blown up very large and were part of the exhibition. She gave me a couple of ideas about where I might find work, but her main advice to me was to develop an accent. Maybe she thought it would make me more exotic than I already was [laughs]. But I didn’t find any discrimination or find myself out of place. I shared a studio with three other photographers—–one was Japanese, one was Jewish, and the other was Norwegian. I was just part of the diversity that is New York City.

Is it true that House & Garden rejected Alexander Calder’s house as a feature story?

It is true. The moment I walked into Calder’s home with the kitchen editor, I knew it was going to be rejected. There were three stoves in that Roxbury, Connecticut, house, and not one of them was less than 30 years old. Nothing there could have encouraged advertising.

You worked closely with both Calder and Wright. Did you find them very different?

Their work ethic was the same, but the difference was that Mr. Wright was starchy and always dressed to the nines even in the desert. Calder dressed more like a blacksmith for every occasion. He insisted on being called Sandy. Frank Lloyd Wright was always Mr. Wright.

How did that translate to their work?

Mr. Wright said, "Give me the luxuries, and I’ll do without the necessities." Sandy wouldn’t buy anything that he could make himself. He made the necessities, and they became luxuries.

How do you feel about photography becoming a more computer-based medium?

Even though I admire it, I don’t think I’m ever going to have the time or the interest in mastering it myself. I know two or three people who do wonderful things with it. I envy them, but they’re not going to have me as competition.

Published

Last Updated

Get the Pro Newsletter

What’s new in the design world? Stay up to date with our essential dispatches for design professionals.