12 Observations About SteamVR

Body-on With The HTC Vive

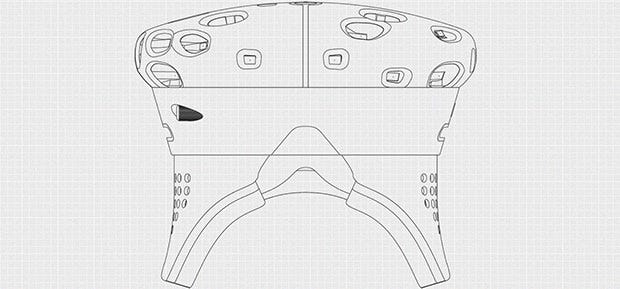

Through a series of fortunate events, I found myself in a backroom at EGX Rezzed last week, wearing a plastic box on my face, clutching a wand-shaped controller in each hand and walking around digital worlds. I was trying out SteamVR, aka the HTC Vive, and it was... well, in the longer term I need to go and have a hard think about how to meaningfully convey experiences* with essentially involve perceiving new realities. For now, I'll be merely practical.

Graham’s already told you about his experiences with SteamVR, and I’m sure there’ll be some repetition here but I’ll do my best to give you as much detail as I can. It is worth stating that a combination of limited time with the system and, frankly, being so engrossed in what it was it showing me does mean that I simply wasn’t able to glean a raft of technical detail.

- I was much less aware that I was wearing a headset than I am with the Rift. I think this is down to a combination of the physical facebox being lighter and more comfortable, and the scene it presents being both less pixelly and ‘bigger’. I’m genuinely not sure how much the latter is down to field of view tinkering (every demo I played was custom made for the Vive, remember) and how much it’s to do with being able to walk around the spaces I was shown. In any case, the screen door effect – which I find extremely bothersome on the Oculus DK2 – was massively reduced. You can still see pixels if you look for them, and it’s not as crisp as looking at a 1080p monitor, but these were issues I had to actively scrutinise the image for, not things which jumped out at me. At no point did I think ‘oh dear, that needs to improve if this thing’s to be a goer.’

- Non-gamers may take to it more immediately than gamers. I kept forgetting to walk around or to crane my head because I’m so used to not being able to, but at the same time I was aware of a dim, instinctive desire to move my legs and bend my back. My brain was interpreting all I saw as a real space, but decades of gaming was getting in the way of natural motion. It came back to me gradually, but for folk who haven’t spent quite so long in front of a monitor it’s going to be there right away.

- The spatial mapping of the controllers is incredibly precise. Holding a wand-shaped controller in my hand (each hand, to be precise) immediately puts me in mind of a Wiimote, and the wiggly, broad motion clumsiness that entails, but these seemed to go exactly where I wanted them to go. The downside of this is that I swiftly became accustomed to such precision, to being able to have the game accurately reflect what I was doing with my hands, to the point that I became slightly frustrated that I was holding a controller. I wanted to reach out and grab objects in the ‘game’, because it so powerfully felt as though that was possible, but sadly I was restricted to jabbing with a plastic stick. Said stick still wasn’t as ‘fast’ as mouse pointing (partly because you’re crossing so much more space to interact with something), but it’s a significant leap on from Wiis et al, and a far more natural way to play VR than trying to use a keyboard and mouse or traditional gamepad blind. Reach out and touch – this, as much as walking, was what VR has sorely needed.

- The majority of the experiences I was shown primarily involved experiencing things rather than effecting things. I’m walking around the deck of a mystical underwater galleon, flicking tiny fish away with the wand or seeing a huge – and I mean huge, the scale of thing when wearing a Vive was genuinely overwhelming – whale swim alongside me. I’m in the depths of Aperture labs as the room’s disassembled around me, giddy with mild vertigo as I stare into cavernous doom beneath me. I’m shuffling away from the edge, whipping my head around to take it all in, but essentially I’m inside a cutscene. A glorious, reality-warping cutscene which makes playing ‘normal’ games seem positively antique, and which I crave more of, but I’m not left much the wiser about what playing a full-length, more traditionally interactive game is going to be like in SteamVR. Maybe that just won’t happen anyway, and maybe it won’t need to – key to getting this thing right is game-makers understanding what is and isn’t appropriate to VR. As Valve’s Chet Faliszek said in his talk at Rezzed, we used to play first-person shooters without mouselook; we didn’t know that we needed mouselook until it came along. Perhaps that will be the case with SteamVR (and its rivals) – one day there’ll be a game containing the little innovation that makes everything fall into place.

- Room size may be an issue. While you can set the distance of the base stations and the in-game scene will adjust its size to reflect this, so in theory this won’t suffer from the excessive space requirements of Microsoft’s ill-fated Kinect, a small space may feel unsatisfactory. Even within a relatively sizeable room I ran into the pop-up walls which denote the boundaries of the in-game world – apparently shown that way because people instinctively respond to a wall as a limitation and generally won’t even try to push through it – a few times. Thanks to the lunacy of the UK housing market, I can’t hope to have too much unfettered floor space to play with, and so am slightly worried I’ll be selling myself short once I’ve got a Vive.

- The most game-y demos were the most Wii-like. Particularly Job Simulator, which involved grabbing assorted oversized kitchen ingredients and attempting to make a basic sandwich or soup out of them, and in that case the joy came from the clumsiness of not having fingers. Opening a fridge, trying to slam an egg onto a counter-top to break it open, hurrying to put tomatoes between bread in time... The laughter and the wonder was that of the Wii, back when that felt fresh and new, but the big difference is that I was in that kitchen rather than looking at it on a screen. I was, I assure you, in that small, cartoonish room. It felt more like being on some gameshow than playing a videogame, as I dashed and pirouetted and fumbled. (It also put me in mind of my toddler’s current love for pretend cooking with plastic food, and for a moment I was right there with her. To be transported back to the simple, pure wonder of a child is a precious thing). It was riotously funny, but it was short and simple. Again, a big question mark hangs over how effectively this tech can handle a bigger and/or more traditional game.

- I never once struggled with a sense of unreality or uncanniness. My brain cheerfully went right along with interpreting a colourful cartoon environment as being the place I was physically in. Clearly, I was aware I was inside a game – this isn’t rewriting consciousness – but that didn’t stop me from perceiving everything around as present and psychical. Being able to walk around and ‘touch’ stuff is an essential part of this fantasy. You can move your whole body as you would move your whole body in life. An Oculus, while still impressive, is by comparison more like moving your head around within a large bowl.

- Relatedly, I was completely aware of where my body was despite being able to see none of it. At one point I was stood too far back when the scene transitioned to a new demo, and my arm clipped through a boundary wall. I couldn’t see my arm, but I knew this had happened because I could see a wall where I knew my arm was. I had a split second of panic – I’ve lost an arm, oh God – before stepping forwards, thus disentangingly my invisible arm from the pretend wall and breathing a sigh of relief. In a way, this mishap was the most powerful moment of the presentation for me, because it involved my truly feeling that my body was inside this made-up place. I suspect we’re going to see some amazing experiments playing with this sort of stuff.

- My favourite demo was the painting one. I swirled the wands around like sparklers, drawing fluid patterns in the air. When I stepped back and around, I saw what had seemed a flat image become three-dimensional spirals, reflecting the depth of each stroke. My lousy brushwork became these wondrous, floating sculptures, like frozen spells. Partly this stood out because it was so very pretty, but mostly, I think, it was because I had some true agency within a SteamVR demo - the others, as I say, broadly involved things happening to me, rather than vice-versa.

- Valve's own demo - the aforementioned Portal vignette - was the most ostensibly impressive, because clearly they always have to go one better than everyone else. The scale, depth and detail was dizzying, and it was very funny too. One aspect of it which hasn't been mentioned so much is that it managed to effectively create the illusion of more rooms beyond the one I was stood in. I couldn't walk into them, clearly (and the scene was set up in a way that I knew, at a glance, they were out of bounds), but my God, the way it made the already large-feeling 'room' I was in explode into enormity... Even if Valve never released anything else for SteamVR themselves, we'd still be talking about this one for quite some time, I think. Also, this stuff is probably going to put theme parks out of business.

- While as I say I can’t speak to longer experiences, SteamVR felt ready for primetime in the way that nothing I’ve tried on Oculus does. I’ve had some great times with my Rift, but it always felt like a collection of compromises coalescing into fascinating experiments rather than a system I could use to play games with, or even would want (even the DK2 gives me headaches, some motion sickness and simple discomfort). I was entirely comfortable in this kit – other than in terms of my embarrassed awareness that an unseen Valve guy was watching me flail about – I didn’t ever have to squint and I felt like I wanted to stay there for as long as my body allowed. (Which probably won’t be long; I drink far too much tea). I’m conscious that the demos I was shown were very carefully tailor-made for a gosh-wow presentation and thus may not be truly indicative of what this is like in a less controlled environment, but even so – moment to moment, it blew everything I’ve tried on any other VR system out of the water. I do expect the wow factor to wear off to some degree, but existing within the scenes it showed me felt so natural that I’m not all concerned about it being a short-lived gimmick. The naturalness is the key to all this, I think.

- Honestly, nothing I’ve told you here is remotely useful. To use this system is to be overwhelmed by it and to want it; to try and break all that down into words is, for now, a fool’s errand. Perhaps, when most of us have got to try it, the shared experience will allow descriptions to mean more, but right now I’m trapped in broadly practical description of what is essentially your consciousness transporting to another direction. I may have nit-picked here, but believe me when I say that SteamVR was a flabbergasting experience. So long as it can roll out widely enough, and so long as it’s affordable, I think this is more than capable of rewriting gaming’s rulebook.

* In a later conversation with a Valve staffer, I ended up equating describing the experience to trying to convey the wonder of seeing one's child grow from baby to toddler, how important and overwhelming it felt to see your little one become capable of basic, everyday motor and communication skills that the majority of human beings have. If you haven't witnessed that yourself, it probably just sounds trite and meaningless. Two entirely different things (and one far more precious than the other, of course), but similar in terms of the impossibility of description.