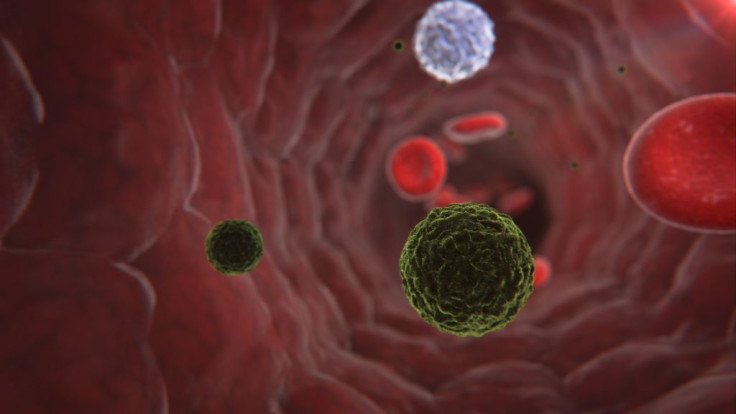

Candida Albicans, Fungus Responsible For Yeast Infections And Thrush, Has Found A Way To Evade Our Immune Systems

The most common disease-causing fungus has a special, though problematic, way of countering our immune system attacks, researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have discovered.

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the findings bring scientists one step closer to fully understanding how Candida albicans, the fungus responsible for vaginal yeast infections and the mouth infection thrush, can cause a deadly infection when it enters the bloodstream.

When the body is taking on an infection, cells burst with free radicals to kill the invading germs. C. albicans and some other fungi use copper as a fuel, feeding an enzyme designed to launch a counterattack on the free radicals. When the body becomes aware of the fungal infection, it flushes copper into the bloodstream to fight, leaving the copper-starved fungus in tissues in places like the kidney.

C. albicans, instead of being beaten by a lack of copper to feed its defenses, actually has a clever way of switching from using copper to using manganese to counter the free radicals, researchers found.

"What we have found here is a very clever adaptation to changes in copper during infection," says study leader Dr. Valeria C. Culotta, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Bloomberg School in a press release. "The more we learn about this pathogen's ability to survive inside a human, the more points of vulnerability we may identify."

C. albicans can only turn deadly for humans when it enters the bloodstream, from where it can affect the liver, kidneys, and spleen. People most at risk are those with compromised immune systems, including chemotherapy patients, premature babies, and those with HIV.

The team discovered the surprising role of copper in immunity, when levels of the metal in the bloodstream go through the roof in an attempt to kill the pathogen. Normally, this would be the end of the story, but C. albicans protects itself by switching its counter attack to an enzyme that relies on manganese instead of copper.

"The fungus laughs in the face of this loss in copper by simply switching metals," Culotta said. "Somehow this fungus has evolved to adapt to this immune system attack. This allows C. albicans to survive when other organisms might be thwarted."

Both copper and manganese are found naturally in small amounts in the human body. Copper has been known to fight off the spread of bacteria — some hospitals in the UK have even switched out steel doorknobs in hospitals for copper ones, because pathogens cannot live on copper.

Culotta says that hopefully there will be a way to design drugs in the future that can disrupt the process in which C. albicans switches from using a copper-based enzyme to a manganese-based one.

Source: Li C, Gleason J, Zhang S, Bruno V, Cormack B, Culotta V. Fungal adaptation to host Cu: swapping metal co-factors for SOD enzymes during Candida albicans infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015.