Karen Lusky

December 2017—Having validation data to support the use of age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs with the D-dimer assay your laboratory uses is a must, and know well the limitations of point-of-care prothrombin time/INR testing.

That advice and more was shared in a “Hot Topics in Hemostasis” session at CAP17, presented by Russell Higgins, MD, and Karen Moser, MD.

The D-dimer test has attracted attention of late because age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs are part of an American College of Physicians clinical guideline for ruling out acute pulmonary embolism.

The ACP guideline authors took an “algorithmic approach to all steps of pulmonary embolism diagnosis, starting with assigning a clinical prediction score,” said Dr. Moser, an assistant professor of pathology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine and a member of the CAP Coagulation Resource Committee (Raja AS, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163[9]:701–711). In general, they recommend patients with a low or intermediate pretest probability of pulmonary embolism undergo D-dimer testing. Those who have a high pretest probability should proceed to imaging.

“Contained within this overall document,” Dr. Moser said, “the ACP guideline tells us that clinicians should use age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds, defined as the patient’s age times 10 ng/mL, rather than a generic cutoff of 500 ng/mL, in patients older than 50 years to determine whether imaging is warranted.”

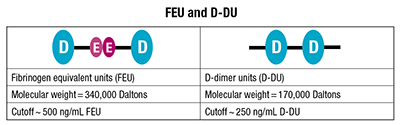

The ACP guideline didn’t stipulate the type of unit for the proposed age-adjusted D-dimer (AADD) cutoff, which could be fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU) or D-dimer units (D-DU). Two FEUs are equal to one D-dimer unit. In published comments, the ACP clinical guideline authors subsequently said their intent was FEUs. (See “FEU and D-DU.”)

The ACP guideline didn’t stipulate the type of unit for the proposed age-adjusted D-dimer (AADD) cutoff, which could be fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU) or D-dimer units (D-DU). Two FEUs are equal to one D-dimer unit. In published comments, the ACP clinical guideline authors subsequently said their intent was FEUs. (See “FEU and D-DU.”)

Where did the age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff come from? The most often cited study, Dr. Moser said, is called ADJUST-PE, “a cute acronym” that stands for looking at AADD cutoffs in patients over 50 for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. The study was a prospective, multicenter validation of AADD cutoffs in patients in that age group (Righini M, et al. JAMA. 2014;311[11]:1117–1124).

The ADJUST-PE researchers didn’t just “pull this cutoff out of thin air,” Dr. Moser said. “They had previously done retrospective work looking at patients in their centers’ populations and subjected those historic data to ROC curve analysis. And it’s just really fortunate for them that what appeared to be the best fit for an age-adjusted cutoff also happened to be really easy to remember: age × 10 ng/mL.”

Dr. Moser

As is standard practice in this patient population, the researchers measured D-dimer in patients who had low to intermediate clinical pretest probability established by Wells or Geneva scoring, Dr. Moser said. “Different centers used different clinical prediction scores. And they used six different D-dimer assays that are commonly used in clinical practice in the laboratory with these cutoffs of either 500 ng/mL or 0.5 µg/mL FEU.”

The study findings were promising. The failure rate, defined as the number of patients who on three-month follow-up were found to have a thromboembolism on imaging after they had a negative AADD result, was 0.3 percent. “So that failure rate—or the three-month risk of VTE in patients who were less than the AADD cutoff—was essentially equivalent to the rate of VTE in patients who had D-dimers less than the manufacturer’s cutoff of 500 ng/mL, or negative pulmonary angiography,” Dr. Moser said. “So they performed comparably, which is encouraging.”

In addition, the AADD cutoff yielded a fivefold increase in negative D-dimer results in patients older than 75. “These are patients who often have renal failure and other comorbidities,” she noted. “They might not be great candidates for some of the contrast-assisted imaging we use.” She cautioned that the study had a limited number of patients of that age.

“The ADJUST-PE results seem to bear out in other trials,” Dr. Moser added, citing a smaller study conducted within one emergency department using five similar D-dimer assays (Mullier F, et al. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25[4]:309–315). A meta-analysis of 13 studies, published before ADJUST-PE was published, also supported the use of AADD cutoffs (Schouten HJ, et al. BMJ. 2013;346:f2492).

Members of the CAP Coagulation Resource Committee shared their thoughts on the ACP guideline in an article published earlier this year (Goodwin AJ, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166[5]:361–363). “Basically I would say the committee’s response is to point out that D-dimer reporting has been confusing for a long time, and it’s critically important to specify the unit type when you are discussing D-dimer values so that anyone who is looking at the values knows exactly what you are talking about,” Dr. Moser, a coauthor of the article, tells CAP TODAY.

The other challenges the CAP committee saw from the laboratory perspective, Dr. Moser says, is that any age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff a laboratory selects has to have validation data to support use of that cutoff with the specific D-dimer assay the laboratory uses. “So whether those data come from large-scale clinical studies in the literature using the laboratory test kit, or whether that comes from an internal laboratory study, there has to be something to support use of the cutoff,” she says. “You cannot just take the proposed cutoff values from the ACP guideline and say, ‘This is going to work with my assay.’ You need to have data to support any cutoff you use in your laboratory.”

In their article, the CAP committee members proposed a short-term strategy recommending that clinical laboratories interested in using AADD cutoffs “consider only specific D-dimer assays adequately evaluated in clinical studies based on the CLSI guidelines,” referring to CLSI approved guideline H59-A, “Quantitative D-Dimer for the Exclusion of Venous Thromboembolic Disease,” published in 2011. The committee also recommended a long-term strategy of harmonizing D-dimer assays and reporting by improving assay performance and unifying reporting units.

The ACP clinical guideline authors said in response, in published comments, that they were referring to “the most commonly used and robustly studied Fibrinogen equivalent units in the ACP Best Practice statement.” They also said, “If D-Dimer Units are used, multiplying the result by ten for patients above 50 years old underestimates the value; rather, providers should consider multiplying by twenty and considering the result in the context of the normal range of their testing laboratories.” They agreed with the Coagulation Resource Committee’s recommended short- and long-term strategies. These and the remainder of their comments were published March 21, 2017 on the Annals of Internal Medicine website.

Dr. Higgins, former chair of and now advisor to the Coagulation Resource Committee, says multiplying the result from assays calibrated in D-DU by 20 does not make sense and does not correlate to the published AADD cutoff calculation. “This is terribly confusing,” he said in an interview, “and it exemplifies the real-world concerns the CAP Coagulation Resource Committee has with the universal application of AADD cutoffs across all assays.” Calculations performed in the laboratory must be handled with caution, he adds, and the calculations by the treating physicians “are equally problematic.”

Dr. Adcock

Dorothy M. Adcock, MD, chief medical officer of LabCorp Diagnostics, calls the AADD cutoffs a “good idea.” Baseline D-dimer levels increase with age. “So the older we get after about 40 to 50 years of age, the higher our D-dimer rises. And this is probably due to underlying atherosclerotic vascular disease. It’s a very well-documented phenomenon,” says Dr. Adcock, an author of the CLSI H59-A guideline on D-dimer (John Olson, MD, PhD, was chair) and lead author and chair of the CLSI H54-A guideline on INR calibration.

Dr. Adcock predicts that use of AADD cutoffs will take off. “I think the article that the CAP Coagulation Resource Committee published in Annals of Internal Medicine will help promote that because they identified studies that were specific for different manufacturers’ kits.” Laboratories using those kits named in the article will therefore be more inclined to report the age-adjusted values.

In the CAP17 session, a poll of the audience was taken. “I would say a minority of participants indicated this was something their clinical colleagues are asking them about,” Dr. Moser says. “But certainly now that this idea has made it into a clinical practice guideline for one of the major internal medicine organizations, I think this is something that laboratories are going to be increasingly facing as the advice is disseminated and the news gets around to other specialties—family medicine and emergency medicine as well as internal medicine.”

The University of Utah hospitals and clinics are using and have been reporting the age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs since mid-2016, says Chris Lehman, MD, medical director of the clinical laboratories and clinical professor of pathology, University of Utah School of Medicine. The laboratory implemented the AADD cutoffs, Dr. Lehman says, because it found out from the medical director of the internal medicine thrombosis service that clinicians were already interpreting numeric results on their own without verification from the laboratory that the test was one that was included in recently published clinical trials and meta-analyses, “and without verification that they were uniformly applying the correct multiplication factor.”

The laboratory reports the D-dimer results as µg per mL fibrinogen equivalent units. The lab information system was set up to compute the cutoff based on the patient’s age by year. “The numerical result is reported with the calculated cutoff with a note stating that a D-dimer result less than the cutoff is considered a negative result,” Dr. Lehman says.

Before making the change, Dr. Lehman discussed the published literature with the thrombosis service medical director to confirm they both agreed there was sufficient data to justify supporting use of the age-specific cutoffs, and that the lab’s D-dimer assay was adequately represented in the published studies.

Dr. Lehman

The CAP Laboratory Accreditation Program 2017 checklist requirement (HEM.37925) says if a different cutoff than what is provided in the manufacturer’s package insert will be used, adequate data must be cited to support it, Dr. Lehman says. “For cut-off data acquired from the literature,” it says, “a negative predictive value of ≥98% (lower limit of CI ≥95%) and a sensitivity of ≥97% (lower limit of CI ≥90%)” are recommended for non-high pretest probability of venous thromboembolism. These recommendations come from the CLSI H59-A guideline, he says.

How large a study would a laboratory have to do on its own? In the CLSI H59-A document, Dr. Moser says, “the recommended study design for validating a VTE exclusion cutoff includes three months follow-up of the included patient population, which should constitute at least 200 patients, and you need to have correlation with imaging studies at the time of diagnosis and over that three-month follow-up period.”

At the University of Utah hospitals, Dr. Lehman hasn’t heard of any concerns or problems with the use of the AADD cutoffs. The medical director of the thrombosis service did report that the positive predictive value of CT scans ordered specifically to rule out pulmonary embolism appears to have increased since the implementation of the age-adjusted cutoffs. The implementation, Dr. Lehman notes, coincided with an institutionwide initiative to increase adherence to recommended clinical guidelines for ruling out PE.

Dr. Lehman’s advice to other laboratories rolling out AADD cutoffs: “Make sure your LIS or EMR can support the calculations required, work with your clinician experts, and use the CAP hematology and coagulation checklist for guidance.”

Oksana Volod, MD, director of the coagulation consultative service and an associate professor of pathology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, recalls that she had just seen the ACP clinical guideline article in 2015 when the emergency department chair sent her the same article by email and said the department believed that type of strategy would decrease unnecessary imaging and the rate of false-positives. From there, “It was escalated to the leadership of the pathology department that [the AADD cutoffs] had to be brought on board,” says Dr. Volod, also a member of the CAP Coagulation Resource Committee.

First the laboratory changed its D-dimer ranges, cutoffs, and units according to the manufacturer preferred units, she says. Second, they examined whether they were comfortable with the age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs. The answer proved to be yes. They use the STA-Liatest D-Di (Stago) quantitative immunoturbidimetric assay, and in an international multicenter study (D-Dimer for the Exclusion of Thromboembolism, or DiET), the assay was shown to surpass the CLSI/FDA guidance requirements for a D-dimer assay, Dr. Volod says. “It was also used in clinical studies of AADD cutoffs for pulmonary embolism exclusion.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management