Bessemer is actively investing in consumer video startups. It’s a space we’ve been focused on for a while now. We invested early in Twitch in 2012 following the company’s pivot from JustinTV (which sold to Amazon last year for ~$1 billion) and were one of the first seed investors in Periscope (which was acquired by Twitter earlier this year while their product was still in beta).

But these are still early days, and I’m eager to meet the next founders who not only imagine a new future for video, but also have the vision, perseverance and technical prowess to take us there.

In thinking about making our next investment in the space, I thought it might be worthwhile to see what can be learned from the past. Specifically, knowing that our early bets in both Periscope and Twitch paid off, I decided to look back at the first investment memos we wrote recommending funding Twitch and Periscope to see how they might shed light on future video opportunities.

Because I found this trip down memory lane to be particularly enlightening, I am open-sourcing certain elements of both investment recommendations with the permission of the founders. Hopefully this gives future BVP Funded teams some sense of how we evaluate the potential of their products and ideas and ultimately make decisions on what to fund.

Because I remembered seeing shades of Twitch in Periscope, I decided to start with Twitch, an investment I championed in partnership with my colleague David Cowan.

What We Saw That We Liked

The Team: We liked the team. They were passionate about the business, solid on execution and knew where to focus to build the organization. Emmett Shear was a first-time CEO, but up for the challenge. Although there were gaps in the team, they were off the charts on a number of “hard to hire” attributes: passion, product vision and empathy for their users.

![Image 1[1]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-11.jpg?w=680)

With the Amazon acquisition behind us, it’s impressive to look back at the path Twitch travelled. The team killed it: Emmett proved himself to be a terrific CEO, managing the technical complexity of scaling such a large site cost-effectively as well as the business challenges of managing the community, cementing deals with both game publishers and console platforms while building a successful advertising and subscription business. In the process, he hired a strong management team, including a CRO, CFO and General Counsel to help him manage the growth.

It turns out we were wrong about the need for an experienced ad sales leader. Immediately after we invested, Twitch’s CRO Jonny Simpson-Bint took this on and built one of the best ad sales teams around.

Pattern Recognition: Twitch had some of the characteristics of a marketplace, which have inherent network effects, tend to be much stickier and are prone to consistent growth if both sides of the marketplace are working properly.

![Image 2[1]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-21.jpg?w=680)

The Idea And Market Size: As we described it to the firm: “Twitch is based on the non-intuitive idea that watching other people play video games is entertaining.” Clearly, Twitch targeted a very specific audience. Maybe we weren’t their target demographic, but their growth was undeniable. We knew they were on to something and conversations with enthusiastic Twitch partners confirmed that.

We did have a long existential debate internally about whether the overall market size was big enough — and believed this to be the key risk to the investment — but, unfortunately, there weren’t many definitive data points we could point to that informed the debate.

![Image 3[1]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-31.jpg?w=473)

In drawing parallels between Twitch and the viral growth of online poker and e-sports in Asia, we convinced ourselves video games could not only become a spectator sport, but that the market size was large enough for Twitch to become a massive site, which is necessary to have any sort of effective advertising business.

It also felt like a pre-existing behavior, as even before the Internet, it’s pretty natural to find a group of friends watching each other play a particularly engaging console game live in the living room. So why wouldn’t this experience eventually migrate online?

Twitch’s metrics pretty much spoke for themselves:

![Image 4[2]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-42.jpg?w=680)

What We Got Wrong

Twitch’s Advertising Monetization Efforts: When we first invested, Twitch was still in the nascent stages of figuring out its media sales strategy, having tried remnant optimization, rep firms and even direct sales. They were working with one specific partner to bundle Twitch’s inventory with theirs in order to garner premium CPMs:

![Image 5[2]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-52.jpg?w=680)

This turned out to be wrong; having a partner rep their inventory actually degraded — not improved — its quality. The better strategy was to sell Twitch on its own. Fortunately, Twitch was able to amicably end the relationship and build their own sales team. By that point, they had grown enough that Twitch was by itself a premium site and didn’t need the help.

Financing Needs: Our memo is completely silent on this topic. Given that the team had operated JustinTV profitably for many years, I think we believed they would be able to scale the infrastructure needed to support Twitch in a capital-efficient way.

It turned out that as traffic continued to ramp faster than expected (and the partner-driven advertising efforts underperformed), we needed additional capital to continue scaling while taking advertising in-house. As a result, we raised a Series C one year later. We try to forecast things like future financing needs, so this was a miss on our part.

Competition For Broadcasters: While we talked a lot about competitive threats from other players like own3d (now defunct) and YouTube, we missed the key issue here: attempts to poach popular streamers would become a regular (and costly) occurrence. The team did a great job fighting and winning this battle through building the better product and attracting the biggest audience for live game viewing, but it was a constant distraction and more costly than we realized.

Mobile: The only mention of the word mobile in reference to Twitch is in this section:

![Image 6[3]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-63.jpg?w=680)

This shows you how much the world has changed over the past three years (or how asleep I was back in 2012). We just didn’t focus our diligence on Twitch’s plans for mobile. Luckily, the Twitch team was more on top of it than we were and built a highly popular mobile app for viewing (which is consistently ranked in the top 25 in the entertainment category on iOS today) and several SDK-based mobile integrations for broadcasting.

Our Conclusion

Would Twitch be big? It was too early to tell, but we were optimistic. The niche was unusual, but we couldn’t deny the traction and potential. For a young company, Twitch exhibited some powerful early indicators of success: a meaningful and growing customer base, a powerful network effect and very strong engagement. We wanted to invest.

![Image 7[2]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/image-72.jpg?w=680)

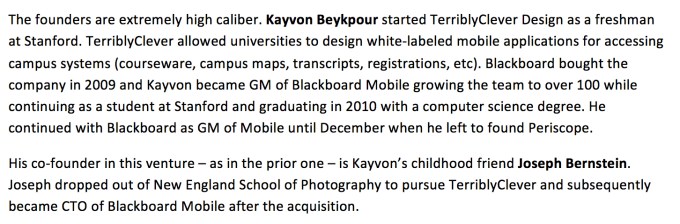

To quote our first investment recommendation, we considered Periscope “an audacious concept”…. whose time may have come. Recognizing elements of JustinTV (the failed predecessor that spawned Twitch), we felt that now both the technology and the market were ripe for Periscope.

What We Saw That We Liked

The Team: As with Twitch, we respected and liked the founders of Periscope. Both teams were scrappy and focused on executing.

As with Emmett at Twitch, Kayvon, Joe and the team turned out to have very prescient vision for future forms of online social interaction and be strong product designers and scrappy operators. I didn’t have as much time to observe their execution, but from the tremendous growth in Periscope (10 million registered users and 40 years of video watched per day, according to a Q&A Periscope stream that Kayvon held), they’ve clearly managed the dual challenges of generating awareness and scaling the technical infrastructure required to support a massive user load.

Total Addressable Market: Periscope had broad appeal. Sure, it was audacious, but given the proliferation of social media access on smartphones, it seemed conceivable. And in this case, there wasn’t as big a concern about only appealing to one particular type of user. As Facebook and Twitter have shown, the inclination to share — either broadly or with a limited set of friends — is pretty ubiquitous if given the right environment and context.

What We Got Wrong

When investing in Periscope’s seed round, I expected them to launch the app, take some time to iterate to get to a compelling product and eventually refine their approach to distribution over the following year. I was surprised (and amazed) by how quickly all of this happened.

Within five months of our investment, they were on the radar screen of large Internet companies like Twitter, and had nailed the interaction and distribution model so cleverly that Twitter was interested in an acquisition even before they had launched a product. Had I known this, I certainly wouldn’t have waited to try to lead the Series A!

Our Conclusion

Again this was a very early investment — much earlier than in the case of Twitch — but the idea and founding team were so compelling that we invested as much as the team would let us. In fact, when I first circulated this investment memo, my colleagues at BVP told me that the idea and timing were so compelling and the team so well-suited to building a great product that I should ask Kayvon to let us invest more. Fortunately, he relented and I was able to more than double our investment.

In reviewing these memos, some of the conclusions are obvious. The team is critical to ultimate success. The timing must be right (e.g., JustinTV wasn’t able to capture the broader Periscope opportunity back in 2007; there weren’t ubiquitous smartphones back then). Having a revenue model that will ultimately fund the operation of the business shouldn’t be an afterthought. But some of the interesting pieces lie in the nuances and patterns.

Both teams thought about the appeal and incentives for all of the various constituents — broadcasters, viewers and game developers/publishers in the case of Twitch, and broadcasters and viewers in Periscope. They thought up front about incentives and rewards (social, financial and otherwise) for being on the platform and how those mechanics differed as the products grew up and the online behavior became more mainstream.

Both teams also thought about the fundamental mechanics of social interactions in the offline world — and how best to bring those into new media in the most natural way possible. This didn’t necessarily mean replicating existing behaviors without any behavior change, as the Internet and mobile affords an opportunity to re-invent and reshape cultural norms.

But each successful social product has to tap into an innate desire to be social in the first place — an obvious statement in hindsight, but not always considered up front. And finally, both teams had tried it before and persisted — with the result being that they were driven to have a bigger impact this time around.