Ring, Amazon’s camera-connected smart doorbell company, has cameras watching hundreds of thousands of doorsteps across the US. It’s also keeping an eye on what local police say online.

Records obtained through an information request show how Ring uses corporate partnerships to shape the communications of police departments it collaborates with, directing the departments’ press releases, social media posts and comments on public posts.

Ring, which was acquired by Amazon in 2018, sells smart doorbells that allow users to monitor their doorstep remotely and operates Neighbors by Ring, an accompanying app that lets users view footage uploaded by other Ring owners.

In recent months, Ring has partnered with hundreds of US law enforcement agencies, offering departments access to its platform in exchange for outreach to residents. Ring says the program gives police more resources to solve crimes, while critics fear the company is quietly building up a for-profit private surveillance network. Ring’s power over police departments’ communications with the citizens they serve is just the latest question about the company’s operations.

Andrew Ferguson, a law professor and the author of The Rise of Big Data Policing said there has been a rise of tech company influence on police work over the past decade, but shaping marketing language within police departments represents a new level of “distortion of public safety rule”.

“Police should not have dual loyalty to a private company and the public – their loyalty should be to the public,” he said. “Any sort of blurring of that line causes us to question that loyalty.”

How Amazon controls social media of local police departments

Pittsburg, Kansas, a city near the Missouri border with a population of 20,000 people, publicly announced a partnership with Ring on 22 April 2019. Emails obtained by the Guardian show Ring first pitched the department in December 2018, offering deals including discounts on devices and sending the police force a free $200 device for every 20 downloads of the Neighbors app. These types of tit-for-tat agreements were a common practice for the company, reporting from Motherboard has showed, and are part of an effort to grow the audience of its app.

On 28 February, once the Pittsburg police green-lighted the program, Ring sent the department a press release template and noted the final communique would have to be approved by Ring before release. The Ring representative also sent Amazon-approved social media assets to be used to promote the Ring program.

“Remember to make sure you highlight your Branch/Text link to try and have your civilians download the Neighbors by Ring App,” he said on 12 March. “I recommend reposting these links to your social media pages once a month to re-engage the community to download the app!”

On 25 April, a spokesman from Ring praised social media posts regarding the partnership and encouraged more. “Let’s keep this community interaction going strong!” he said. “Hopefully, the department can get a ton of people to download the Neighbors App from your specific link!”

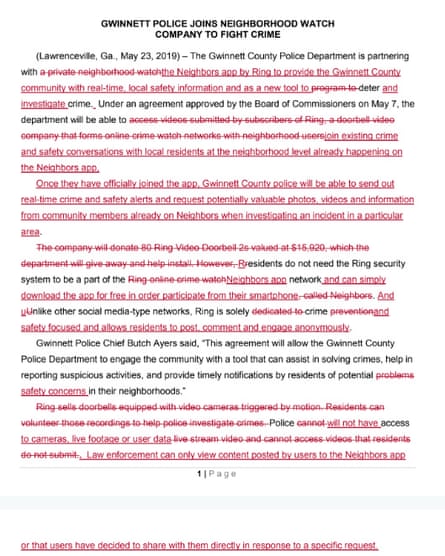

Emails between Ring and police officials in Gwinnett county, Georgia – a county near Atlanta with a population of around 900,000 – show a similar script.

Ring first contacted the department in August 2018, and police approved the partnership in May 2019. Ring donated 80 doorbells to police, valued at $15,920. It heavily edited the press release about the program, removing one sentence that said “the company will donate 80 Ring Video Doorbell 2s, valued at $15,920, which the company will give away and help install”.

Ring also changed wording from the police department that said the department “will be able to access videos submitted by subscribers of Ring” to say the department will “join existing crime and safety conversations with local residents”. Ring also deleted a sentence saying “police cannot access live stream video”, changing it to “police will not have access to cameras, live footage, or user data”.

The Ring representative also offered to cross-promote alerts from Gwinnett county police directly to the Amazon-owned Facebook page, sharing images of people who had not yet been charged with a crime publicly. A spokesman from the Gwinnett county police department said separate from Ring, it often publishes images and videos of suspects in crimes on social media to help identify them for criminal prosecution.

Gizmodo documented similar arrangements between the company and police departments in California, Florida and Texas.

“Ring provides sample social media content for police departments to utilize at their discretion to inform their jurisdictions about their partnerships with Ring,” a spokeswoman for the company said. “Ring requests to look at press releases and any messaging prior to distribution to ensure our company and our products and services are accurately represented,” she added.

Amazon’s social media advising is ongoing

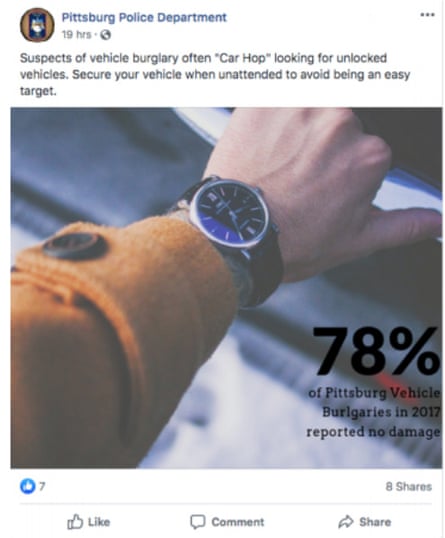

Emails between Ring representatives and Pittsburg police show the company continued to shape police rhetoric online, months after the launch of the partnership. In one email the representative encourages officers to tell locals more about crime statistics.

“I just wanted to reach out and say great job with the response you made with neighbors commenting about crime going up etc,” the email says. “That’s an exact comment residents need to see coming directly from the department to put things into perspective.”

In another post, a Ring spokesman tells police to comment more frequently on crime posts to encourage users to report on the Neighbors app when they see crime in the neighborhood. “This is exactly the interaction your community needs to see,” he told an officer who commented on a post about a woman whose car had been broken into.

A spokesman for the Pittsburg police said Ring and its Neighbors app represent an extension of its information dissemination and crime reporting efforts in the general community.

“We recognize that social media is a vast and readily accessible public communications mechanism and are trying to openly engage the community through as many platforms as possible to encourage people to become involved and report crime or suspicious activity,” a spokesman said. “Ring is another social media platform through which we can communicate and share information with the community and to promote better transparency.”

Andrew Ferguson, the law professor, said the language Ring encourages police departments to market Ring products to private citizens, changing the relationship between citizens and the police.

“The purpose for this kind of commentary is to fuel a narrative that these devices are effective in stopping crime, that there is a high rate of crime and thus people need these devices, and police support a particular brand of camera over other brands of camera,” he said. “All of those are questionable choices for a public safety organization that should have a primary purpose of serving public safety and not corporate marketing.”

These kinds of interactions “undermine public trust in law enforcement”, echoed Matt Cagle, a technology and civil liberties attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union said.

“It is shocking to see a private corporation dictating what public officials will say to community members about public safety issues,” he said. “Ring answers to Amazon shareholders, and police are supposed to answer to the public. That is the core tension in these relationships.”

Privacy advocates want police surveillance off our doorsteps

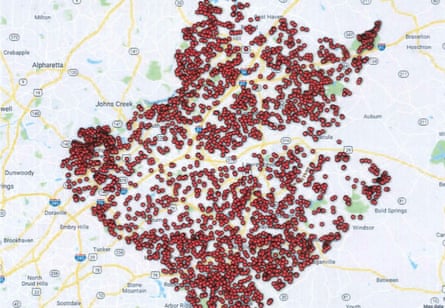

Ring had a 97% share of the video doorbell market as of 2018, according to market research firm NPD group. The company had more than one million US customers when it was acquired by Amazon in 2018. A map of existing users in Gwinnett county shared by the company with the police force showed hundreds of cameras in the new area of partnership.

The company has now created partnerships with more than 400 police forces, according to the Washington Post, including partnerships with law enforcement agencies across the US in places including Florida, Virginia, Atlanta, California, and Texas.

Ring said police do not automatically have access to Ring video streams. Law enforcement has access to a portal, and then needs to directly request information from Neighbors app users if it wants to watch footage. Ring says it does not share information with law enforcement unless a user consents.

But the company’s law enforcement partnerships have faced criticism from privacy and criminal justice activists. Advocates fear that the cameras will allow police access to surveillance footage while bypassing the public process to approve more traditional security cameras. They have pointed out that contracts between police and Ring often face little public scrutiny and experts have raised concerns over requests from Ring to get access to police department’s computer-aided dispatch feeds.

Advocates have also questioned how comfortable users feel in denying law enforcement requests. And they have pointed at problems of discrimination that Ring, and the broader industry of neighborhood social networks, have faced.

Here's the police video-request email Ring sends to users. Note the difference between the big "Share now" button and "Please unsubscribe" link. Also: "If you would like ... to make your neighborhood safer, this is a great opportunity." (Who could say no?) https://t.co/db4w8nDzey pic.twitter.com/Rv8ffccR2R

— Drew Harwell (@drewharwell) August 28, 2019

“What often happens in instances of increased surveillance is that there are more arrests of ‘suspicious characters,’ which often end up being people of color not breaking any laws,” said Caroline Sinders, a machine learning designer in Berlin who studies the intersections between technology and harassment. “This is going to result in more people of color being hassled and arrested for just existing.”

Jamie Siminoff, the founder of Ring has said Ring keeps “customers, their privacy, and the security of their information” at the top of its priority list. “Our customers and Neighbors app users place their trust in us to help protect their homes and communities and we take that responsibility incredibly seriously,” he said in a blogpost about Neighbors.