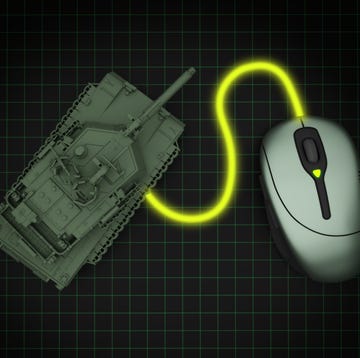

A string of armed robberies could be deeply connected to your digital privacy, and how easily the government can track you and your phone in the future. The reason is a case that's set to hit the Supreme Court on Wednesday.

It's called Carpenter v. United States. It concerns Timothy Carpenter, who was convicted of organizing and supplying guns for a number of robberies in the Midwest and sentenced to more than 100 years in prison. The thieves in those robberies targeted Radio Shack stores and other electronic outlets, and made off with sacks full of smartphones—somewhat ironically, since Carpenter's phone is at the heart of the case.

The New York Times reports that among the evidence against Carpenter, the prosecutors had one particularly damning weapon up their sleeves. Law enforcement asked Carpenter's carrier for months of phone records, which would establish his whereabouts by which cell towers his phone had pinged. All in all, the phone company turned over 127 days of records that placed Carpenter at nearly 13,000 locations during that time, his lawyers say. Police say those records say Carpenter was at the locations in question at the time of the robberies. Carpenter says that all of this amounts to an illegal search, in violation of his Fourth Amendment rights.

It's becoming increasingly common for prosecutors to seek this kind of phone evidence from tech companies. (By the way, the big tech companies filed a brief in the case that you can read here.) But this legal challenge could have huge implications for everybody's privacy in the digital age. Says the Times:

The court’s decision, expected by June, will apply the Fourth Amendment, drafted in the 18th century, to a world in which people’s movements are continuously recorded by devices in their cars, pockets and purses, by toll plazas and by transit systems. The court’s reasoning may also apply to email and text messages, internet searches, and bank and credit card records.

On the one hand, you've got law enforcement's take on this issue: Look, you agree to the carrier's terms of service when you sign up for your phone. You know they can track your location. Therefore, you have no reasonable expectation of privacy. You have voluntarily turned over your data to the phone company, which is a third party. Therefore, the police needn't get a warrant to ask for this information. You can see the legal logic here.

On the other hand: Really? No reasonable expectation of privacy whatsoever? Everybody knows their smartphone can track their location, but few of us take the time to consider the full and deep consequences of that fact—including that the police might use your phone records to determine everywhere you've been over the span of months or years. The implication seems to be that users are a bunch of dummies for agreeing to the phone company's litany of legalese. Never mind that the alternative is to live without a smartphone, which is increasingly difficult if not impossible for many people who want to live and work in the 21st century.

There is some case law for those hoping for more legal privacy to be extended to our devices. The Times says that SCOTUS ruled in 2014's Riley v. California that the police generally need a warrant to search your phone if they arrest you, showing that the high court generally understands the need to extend some privacy protections to our phone.

As Justice Roberts wrote in that decision, our phones "could just as easily be called cameras, video players, Rolodexes, calendars, tape recorders, libraries, diaries, albums, televisions, maps or newspapers.” For a huge number of people, their whole lives are inside their phones—something the authors of the Fourth Amendment surely never could have imagined.

Andrew's from Nebraska. His work has also appeared in Discover, The Awl, Scientific American, Mental Floss, Playboy, and elsewhere. He lives in Brooklyn with two cats and a snake.