Fetuses Prefer Face-Like Images Even in the Womb

A pioneering study that showed images to babies in utero paves the way for more research into our prenatal mental abilities.

It is dark in the womb—but not that dark. Human flesh isn’t fully opaque, so some measure of light will always pass through it. This means that even an enclosed space like a uterus can be surprisingly bright. “It’s analogous to being in a room where the lights are switched off and the curtains are drawn, but it’s bright outside,” says Vincent Reid from the University of Lancaster. “That’s still enough light to see easily.”

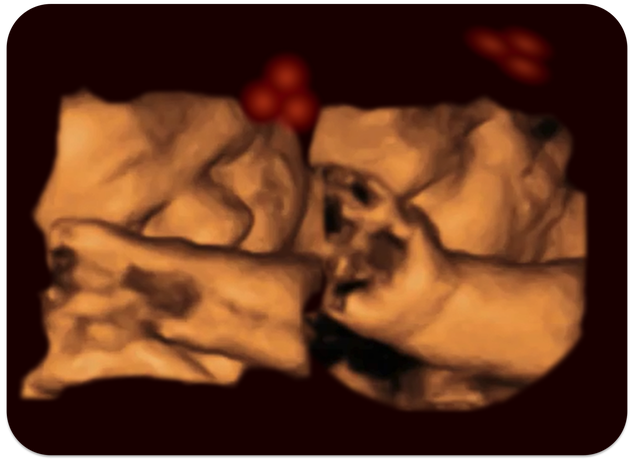

But what exactly do fetuses see? And how do they react to those images? To find out, Reid shone patterns of red dots into the wombs of women in the third trimester of their pregnancies, and monitored the babies within using high-definition ultrasound. By looking at how the babies turned around, Reid showed that they have a preference for dots arranged in a face-like pattern—just as newborn infants do.

“This is the first time that anyone’s been able to deliver an image to a fetus,” Reid says. And it will finally allow scientists to study the mental abilities of humans at the earliest possible stage of our development—before we are even born.

For decades, scientists have known that third-trimester babies can perceive sounds and other stimuli while still in the womb. For example, in 1980, Anthony DeCasper and William Fifer asked pregnant women to read The Cat in the Hat to their fetuses, again and again for the last 7 weeks of their pregnancies. As soon as the babies were born, DeCasper and Fifer gave them pacifiers. The babies could then choose to hear a recording of either The Cat in the Hat or a different children’s story, by sucking at different times. And they sucked for the cat.

“People showed that a fetus could learn, was aware of elements of language, and preferred its mother’s own voice,” says Reid. But while such studies looked at hearing, touch, taste, and balance, vision was bizarrely neglected. A lot of researchers have looked at how newborns see the world, but most suspected that there was no way of doing similar tests before babies were actually born.

Reid proved otherwise. He and his colleagues essentially replicated studies that have been done with infants since the 1960s, showing that they prefer to look at human faces over all other kinds of images. The preference is so strong that even a vaguely face-like image will draw their attention—like a triangle of dots with two on the top and one at the bottom. If you’re being generous, you could argue that this pattern resembles two eyes and a mouth. But more importantly, it has many of the features found in actual faces—it’s top-heavy, symmetrical, and high in contrast. The resemblance is similar enough that babies are drawn to this pattern more than an inverted one, with two dots on the bottom and one on the top. And so, according to Reid, are fetuses.

First, he and his colleagues created a mathematical model that would predict how light would pass through a mother’s tissues, and what different images would look like to a fetus. Next, they used their model to calibrate two images—an upright triangle of red dots, and an inverted one. They shone these patterns into the bellies of 39 pregnant women, and then slowly moved the lights to the side. And using ultrasound, they could see that the fetuses would turn their heads.

They didn’t always do so, though. They were more than twice as likely to track the movement of the upright face-like triangle than the inverted one—exactly the same pattern you find in newborn babies. “This tells us that the fetus isn’t a passive processor of environmental information,” says Reid. “It’s an active responder.”

It also confirms that the preference for faces isn’t the result of experiences that happen after birth. Some scientists have suggested that babies imprint on the first things they see—usually their mother’s face—in the same way that baby chicks or ducklings do. It’s very hard to test that idea: If imprinting happens and is important, it would be unethical to deprive a baby of that stimulus. “But this study rules that out,” says Reid. The preference already exists in utero.

Between 20 and 24 weeks into gestation, a fetus is upright in the womb, and its eyelids unfuse. It can then see, and what it sees depends on how light is bent, distorted, or blocked by the mothers’ body on its way into the uterus. Perhaps, Reid suggests, those patterns of light could influence the development of the fetus’s eye and brain, making the upper half of visual field more sensitive. That would create a bias towards top-heavy, face-like shapes.

“This is just a conjecture,” he admits, but one that he’s finally in a position to test. His team is now checking if fetuses share other infant biases, like a fondness for biological motion—movements that resemble those of living things. He also wants to know if they have a number sense, and can tell the difference varying quantities of dots. “If we can show that they do, we’re talking about fetal cognition, which is a whole new ballgame for developmental science,” he says.

“It’s important research because, compared to the other senses, we know very little about the development of the visual system before birth,” says Elizabeth Simpson, a child psychologist from the University of Miami, who was not involved in the new study. She suggests that Reid’s techniques could be used to detect cataracts and other vision problems before babies are even born, allowing doctors to perhaps correct such problems as early as possible. “We could also test whether they imitate facial expressions, such as poking out the tongue, as newborns do,” she says. “And we could also assess if fetuses, like newborns, integrate information from multiple senses—whether they look longer at matching audio-visual stimuli than at mismatching ones.”

But Simpson advises caution. It might not be good for fetuses to get too much light exposure early on in life, and scientists should check for risks in animal studies. “That’s why we made sure that the amount of light we used is only half of that already thought to penetrate the uterus,” says Reid. “But I would certainly discourage people from shining light at a fetus. If it’s too bright, it could be aversive or harmful.”