For a historical preservation project, it’s a worst-case scenario: No detailed drawings, no existing structure and a handful of black and white photos.

But modern technology and a team of PhD-level minds intend to resurrect a gem of architectural history that was lost in Banff, Alta.

For the past year, Yew-Thong Leong and his team of academics have been poring over old photographs, analyzing rock colours, pondering lumber gathering methods and entering data into digital models to reverse engineer a public pavilion in Banff.

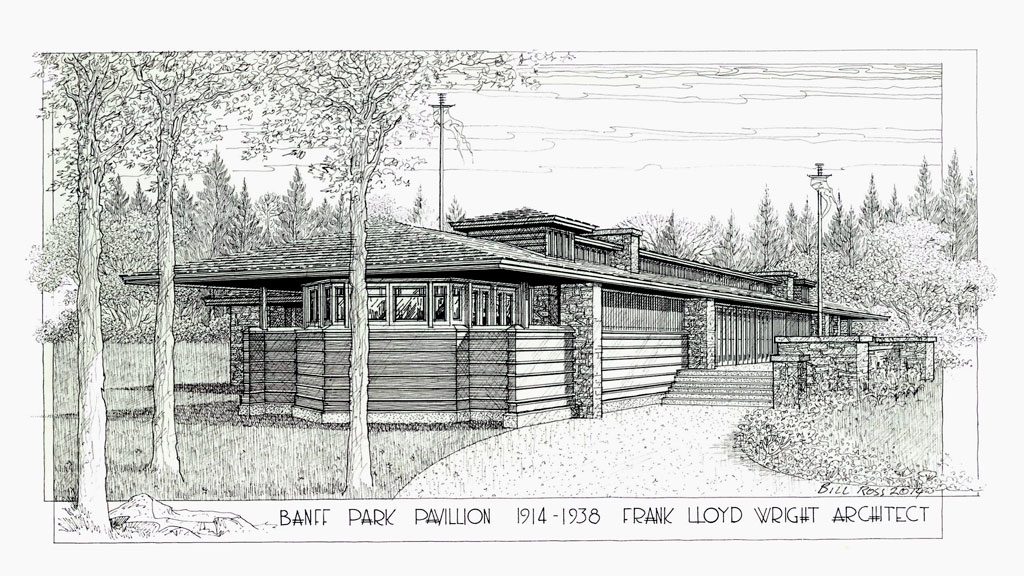

Leong, an architecture professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, specializes in building preservation and conservation. He and a handful of other world-renowned academics recently wrapped up the first stage to reconstruct Canada’s only public structure designed by influential American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

The structure was an example of Wright’s iconic Prairie School-style which integrated design into the natural landscape and favoured horizontal lines. Leong and the team have been doing the work pro-bono with the support of Ryerson.

Wright designed and built over 500 structures, including the Guggenheim Museum, Fallingwater, the Frederick C. Robie House and the pavilion in Banff, which succumbed to flooding and frost in the 1930s. A skatepark and baseball diamond now sit on top of the original site of the pavilion.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative, a not-for-profit that sought Leong’s help, hopes with the blessing of the city, the pavilion can be rebuilt, nearly exactly as it was in 1914. The group then intends to gift it to the city.

But at first glance, it is a daunting task.

“We are in the worst possible case scenario,” said Leong.

“The original drawings from the national archive were skimpy with only some geometry and dimensions.”

Leong also explained at the time, lots of work, like masonry, was left ambiguous during the planning stage and figured out later by craftsmen with local knowledge and methods at the direction of the architect. Often this work was never recorded.

“They relied on amazing craftsmen to make decisions onsite,” Leong said.

But working with historians, the team was able to figure out many of the local materials and methods likely used.

Leong is also an expert of early 20th century construction and understands the Japanese and Italian influences Wright was soaking up at the time.

The team was also able to use photogrammetry to determine the dimensions of the masonry and map it. Using BIM, the team was able to digitally build the entire structure. Leong believes they have figured out the plans and dimensions of the original structure to roughly 95 per cent accuracy.

The next task will be raising the funds to get the project built and getting approval from the city, which is in Banff National Park. If approved, the team will then design plans to actually build the structure, likely with some minor adjustments like modern electrical wiring and flood protection.

According to city council documents, the timing of the original pavilion’s construction in 1914 was not ideal. It was repurposed during the First World War as a quartermaster’s stores by the federal Department of Defence. Two floods also impacted the pavilion between 1920 and 1935. Frequent temperature changes and neglect also damaged the building.

In 1938, only 24 years after its construction, the Banff Pavilion was dismantled.

The city now must determine the merits of rebuilding.

“There’s a broader philosophical question about building in the national park,” said Jennifer LaForest, Banff development planner. “It was a bit of an anomaly and it didn’t exist for very long, but it sets us apart from other communities. It existed in a strange part of town history and isn’t really ingrained in the town memory and there isn’t really anyone around that remembers it.”

LaForest explained the footprint of the potential site is legislated by Parliament and also has an already approved plan with clear community objectives. The council has asked for a more specific submission from the not-for-profit with their plans and details on the building’s life cycle and its maintenance needs.

“The area is intended for community recreation rather than visitor amenities,” said LaForest. “We have to be careful how to balance that as there is already a lot of stuff intended for visitors. These community areas have become more important.”

LaForest said ultimately it will be up to government officials to consider the merits of building in a national park, restoring a rare piece of architectural history and serving residents.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed