Table of Contents

There may be no topic in the world of business that spurs such impassioned responses than self-serve versus manual cancellation of a subscription. Let’s just say the word “evil” gets tossed around a lot.

There’s a lot that gets overlooked in the conversation about this, so I want to walk through the different sides of the arguments for/against and try to keep things as rational as possible. I sincerely want to have a constructive conversation about this topic as I believe there are in fact scenarios and reasons when removing self-serve cancellation makes sense for a business.

So, we’ll talk through when it makes sense, how to do it in a way that is as customer-friendly as possible as well as how not to do it. I’ll also address some of the common concerns people have with removing self-serve cancellation.

Note: This is a topic people feel incredibly passionate about. The one thing I ask is that you at least entertain the idea that the world isn’t black and white and that most businesses (especially small startups) aren’t inherently evil. Everybody’s winging it.

One startups experience with removing self-serve cancellation

Back in February 2015, we were having some serious issues with churn. It had been creeping up from an already-less-than-stellar 6% to an unsustainable 13%.

If prior months’ trend were any indication, in a matter of months we’d be hemorrhaging customers at a rate that would have put us out of business. Something needed to change.

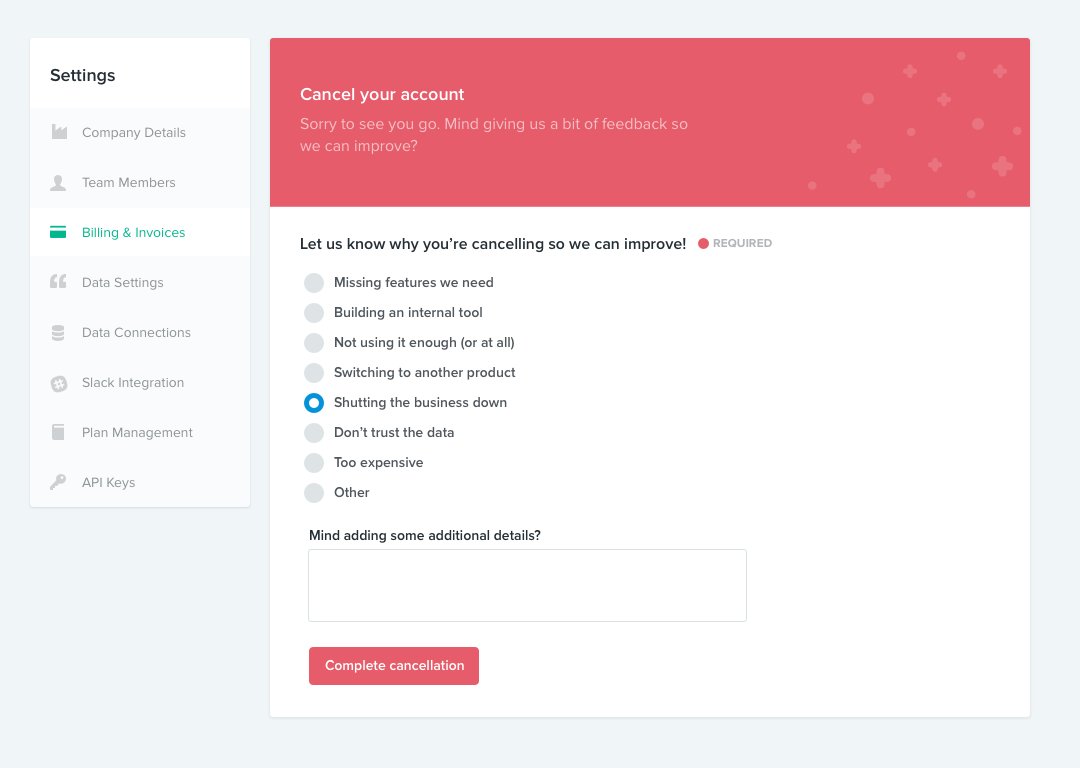

We were trying all sorts of methods of getting feedback, from including a “required” open text area for feedback when cancelling, to requesting phone calls, and everything in between. Our one and only goal was to figure out why people were cancelling.

But none of the feedback we were getting was actually actionable. Those open text areas would just result in either people slamming their hands on their keyboards at random or at best writing “cancel. bye.” The emails and phone calls we were trying to schedule generally fell on deaf ears.

No matter what we tried, we just weren’t getting enough actionable feedback to fix anything.

So, we decided to take a more drastic measure. We removed the ability to cancel directly in the app. You’d need to message us if you wanted to close your account.

We certainly had some reservations about this. No one loves an extra step to cancel a service. But we were committed to handling cancellations requests as fast as possible while being as genuinely useful as possible (which I’ll talk about in a moment).

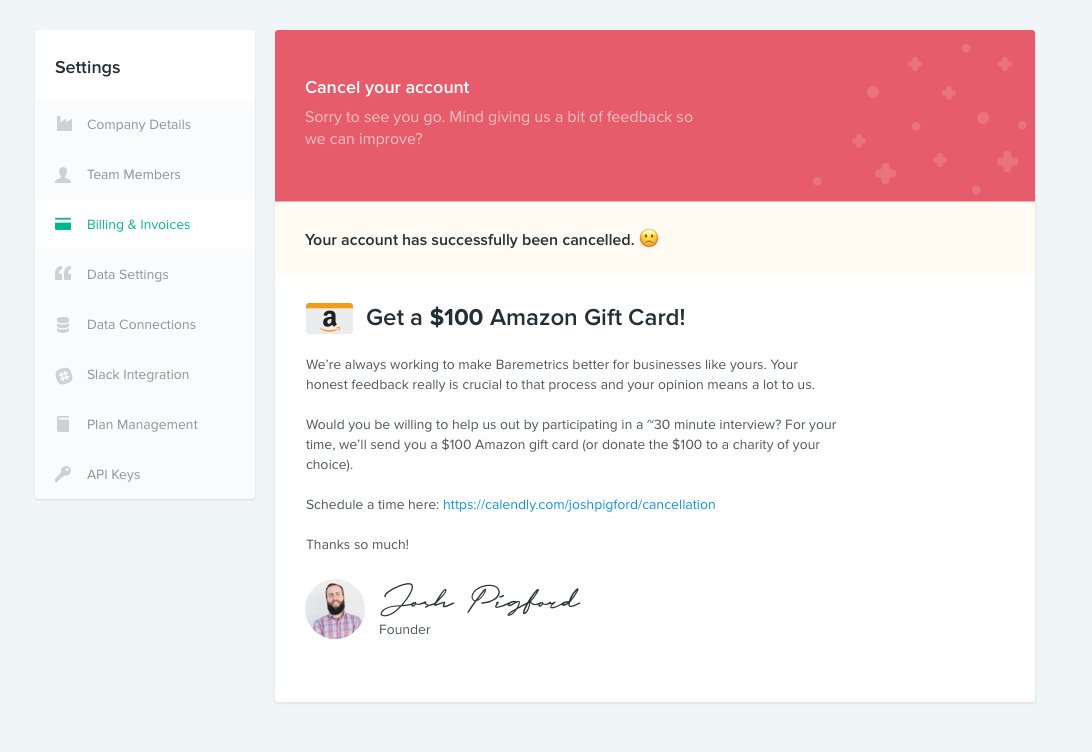

The results were fantastic. Not only was the feedback actionable, but we were actually able to save about 15% of cancellations! People would write in saying they wanted to cancel because we lacked certain functionality, but in many cases we either had a feature they needed or were about to release it.

For a solid year, the feedback from manual cancellations continued to be quite actionable and we could count on one hand the number of people who responded negatively to the process.

We cut our churn in half during this period thanks directly to the feedback we received. And more importantly, this literally saved Baremetrics.

But as our churn decreased and the major holes were plugged, we found the feedback less and less useful. The reasons for cancelling were boiling down more to things we had no control over (going out of business, changing business models, acquisitions, etc).

After nearly 2 years of manually processing every cancellation, we reimplemented self-serve cancellation.

How to do manual cancellations in a way that doesn’t bring out the pitchforks

The reason our manual cancellation process worked for as long as it did is that we were committed to doing it in a timely and helpful fashion.

When I say that someone was required to contact us to cancel, most people instantly think of some terrible experience they’ve had with their cable provider. Sitting on the phone for hours, getting transferred to a dozen different sales reps, being offered increasingly larger discounts to stick around.

Nothing could be further from reality with our process.

The key to doing manual cancellations correctly comes down to two things.

- Make it unbelievably easy to get in touch. We had a whole pile different ways to get in touch nearly instantly. You could live chat, send in an email, send an in-app message, tweet at us or yes, if you wanted, you could call us.

- Respond quickly. They’ve made the move to get in touch, now you need to reply as fast as humanly possible. Many times we’d respond within seconds or minutes, and almost always within a few hours (even during the evening).

After someone would write in asking to cancel, we’d respond with something to the effect of…

Hey Sally, happy to take care of that for you! Before we do that, would you mind letting me know why you’re canceling? Would love to learn how we could have served you better.

Most of the time, we’d get great feedback about exactly what was going on and why Baremetrics wasn’t a good fit for them any more. We’d then promptly cancel their account (and many times refund them) and wish them well.

What you definitely should not do is argue with the person to try and convince them to stay around. You should try to be as genuinely helpful as possible throughout the process. You want to understand why they’re cancelling and then act accordingly.

This is why we were able to save some 15% of cancellations because we found that those customers didn’t want to cancel, we had just done a bad job of surfacing functionality within the app. So when we identified what was going on, it was actually more helpful to show them they didn’t need to cancel than it was to just go ahead and process without asking any questions.

When to try out manual cancellations

So when does it make sense for your business to test out manual cancellations? It certainly isn’t for everyone and I don’t believe it’s a great long term solution, but it can be a really effective tool.

If you’re churn rate is double-digits and you aren’t sure of the exact reasons why, then trying out manual cancellations for a period of time is likely worth it for you.

Churn is ultimately the result of your product not solving the problem the customer has. If you have double-digit churn that’s increasing and no clear path to reduce it, you’ll soon have an existential crisis on your hands.

Manual cancellations can make a huge difference in your ability to grow (or to even continue existing as a business).

John O’Nolan of Ghost said it well…

1) Do A+ thing & go out of business

2) Do B- thing & survive“Founder” means making this decision 100x per week. 1 user’s poor cancellation UX can fuel positive UX changes for 100,000 new/existing users to have a better experience.

You should keep doing manual cancellations only as long as the feedback is actionable and you’ve pinpointed what needs to be done to fix your churn problem.

Common objections to requiring a customer to contact you to cancel

I believe I’ve covered most of the reasons why doing manual cancellations can be really beneficial to your business, but let’s tackle the two most common objections.

“It’s a dark pattern”

I’ve heard this one so many times, so let’s be clear: “I don’t like this” does not mean it’s a “dark pattern”.

A dark pattern is “a user interface that has been carefully crafted to trick users into doing things.”

Manual cancellations aren’t tricking anyone. They aren’t preventing anyone from cancelling their account. Are they the most ideal UX? No. Building a business is constantly making the “A+ and die/B- and survive“ decision.

“It’s not customer friendly”

Partially agreed. There’s more to it, though. Yes, being able to click a single button and be done is the easiest thing for the customer, but remember the scenario I mentioned above about missing features? Many times (15% of the time in our case) a user wanted to keep using Baremetrics but thought we were missing a feature they needed.

Manual cancellations surfaced that in a way that “instant, self-serve cancellations” never would have. The feedback from those cancellations not only let us help those customers, but it helped us as a business improve the product in a way that future customers wouldn’t have those issues.

Arguably that makes the practice “friendly” for many customers. Again, temporary less-than-ideal user experience for a few in exchange for long-term positive improvements for many.

Business is a balancing act

At the end of the day, you will frequently have to make tough decisions to stay in business. That doesn’t make for great marketing copy, but neither does “we’re shutting down because we couldn’t figure out how to make the product better”.

The most dangerous thing you can do in business is assume that there’s only one way to do it, that there’s a formula for success, that what worked for Company A will also work for your company.

None of those are true.

Businesses are unique, living, breathing, ever-changing organisms. If you sit idly by assuming things will just magically improve, your business will die. Some decisions will result in unhappy customers, but no decisions will result in more unhappy customers than the one to shut the business down.

Find the balance of doing what’s the “most best” for both the business and the customer. The two go hand-in-hand. Some days the scales will tip more towards one over the other and vice versa. But as long as you work on simultaneously improving both, you’ll be just fine.