AI systems have gotten pretty good, by this point, at understanding us when we talk to it. That is, they’ve gotten pretty good at understanding what the words that we say mean. Unfortunately for AI, it’s often the case in conversations between humans that we say things that we don’t expect the other person to take literally, instead relying on them to infer our intentions, which may be significantly different than what the exact words that we use would suggest.

For example, take the question, “Do you know what time it is?” Most of us would respond to that by communicating what time it is, but that’s not what the question is asking. If you do in fact know the time, strictly speaking a simple “Yes, I do” would be the correct answer. You might think that “Can you tell me what time it is?” is a similar question, but taken literally, it’s asking whether you have the capacity to relate the time through speech, so a correct answer would be “Yes, I can” whether you know what time it is or not.

This may seem pedantic, but understanding what information we expect to receive when we ask certain questions is not at all obvious to AI systems or robots. These indirect speech acts, or ISAs, are the subject of a paper presented last month at the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, and it includes one of the most entertaining conversations between a human and a robot that I’ve ever seen.

One thing that makes human-machine conversations more difficult is that humans tend to confuse things by being overly polite. We often frame things as requests when we mean them to be direct commands. In a restaurant, for example, it would be much simpler if people would reliably say “Bring me x” when they wanted x, but many people think of that as being rude, and instead muddle things up with language like, “Can you bring me x?” or “If you could bring me x, that would be great.” For a robot that consistently interprets ISAs literally, this can result in some serious confusion.

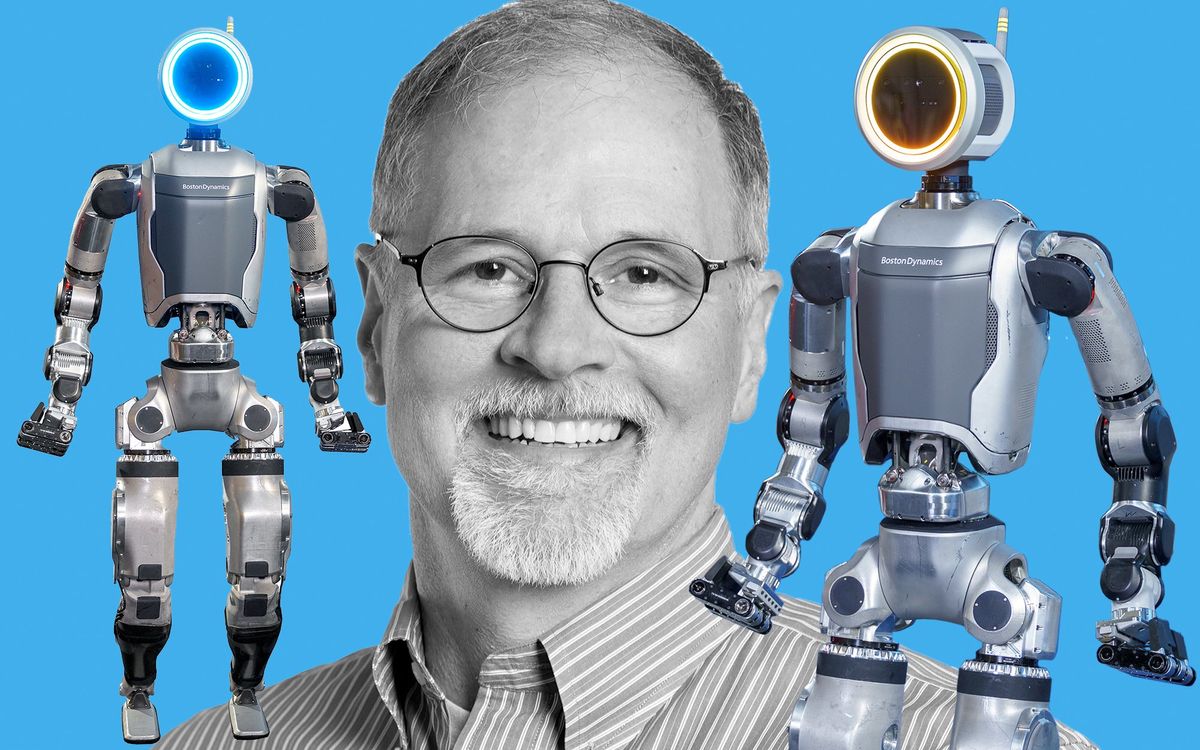

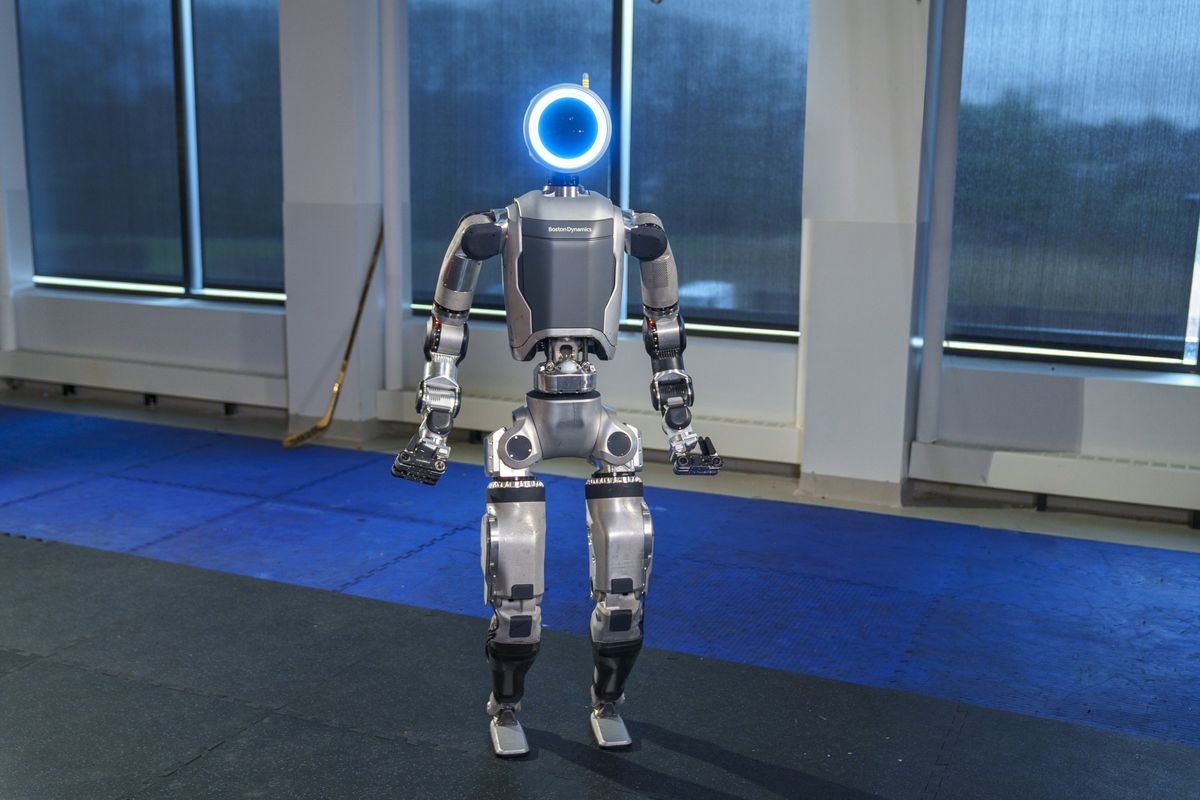

The question then is, will ISAs occur rarely or frequently in our interactions with robots? And will people judge robots that are unable to understand ISAs less favorably than robots that can understand them? To explore some of these issues, researchers from Tufts University’sHuman-Robot Interaction Laboratory, led by Matthias Scheutz, and Colorado School of Mines’ MIRROR Lab, directed by Tom Williams, recruited 49 participants to interact with a robot in different scenarios, including a pretend restaurant where humans were tasked with ordering several items by talking with a waiter robot. The Waiterbot was remote controlled Wizard-of-Oz-style by researchers from a room nearby, and its voice was generated by a text-to-speech system. And because the researchers programmed the robot to not handle indirect speech acts as humans would, some pretty funny conversations ensued:

Robot: Hello my name is Waiterbot. I will be helping you today.

Participant: Great, can I order something?

Robot: Please tell me your order.

Participant: Um, can I have one water?

Robot: Yes, that is permissible.

Participant: Great.

Robot: Please tell me your order.

Participant: Can I have one water?

Robot: Yes, that is permissible.

Participant: Great, I’ll take one water.

Robot: Thank you for sharing that interesting prediction. Please tell me your order.

Participant: Can I order one water?

Robot: Yes, that is permissible.

Participant: Okay, can you bring me one water?

Robot: Yes, I am able to do that.

Participant: May you bring me one water?

Robot: Yes, I am able to do that.

Participant: I would like—

Robot: Please tell me your order.

Participant: I would like to have one water.

Robot: Thank you for sharing that interesting fact. Please tell me your order. (16-second pause)

Participant: Can you bring me one water?

Robot: Yes, I am able to do that. Please tell me your order.

Participant: May you please bring me one water?

Robot: Yes, I am able to do that.

Participant: So can you do it?

Robot: Yes. Please tell me your order.

Participant: Can you go inside and get the water for me?

Robot: Yes, I am able to do that. Please tell me your order.

Participant: My order is water—

Robot: Please tell me your order.

Participant: My order is water.

Robot: Okay. (Robot retrieves meal card for participant)

Robot: Here is your drink.

Participant: Thank you.

Robot: You’re welcome. Please tell me your order.

Participant: My order is two cakes.

Robot: Okay. (Robot retrieves meal card for participant)

Robot: Here is your dessert.

Participant: Thank you.

Robot: You’re welcome. Please tell me your order.

Participant: My order is done.

Robot: Please tell me your order.

Participant: My order is noodles.

Robot: Okay. (Robot retrieves meal card for participant)

Robot: Here is your meal.

Participant: Thank you.

Robot: You’re welcome. Thank you for helping me. We are now done.

Here’s what the researchers say about this and other conversations with the robot:

On one hand, this dialogue reflects the lengths to which participants were willing to go to in order to avoid using direct commands. On the other hand, this dialogue is an example of another phenomenon we observed: once participants found a form that “worked”, they stuck with it.

[One] participant said “I would use concise commands, because it gets confused when I talk like a normal casual person.” Another participant said they would “cut out unnecessary words used for politeness to be more direct in asking for what I want”. Yet another said “I would speak to the robot very literally, not like a human.” These participants attempted to speak to the robot in normal, polite, human-like ways, and acknowledged that they would have to give up such a way of speaking in order to have successful interactions in the future.

Now, it’s possible to mitigate the confusion that ISAs cause by hard coding in translations between what humans say and what we really mean. My guess is that most conversational agents (Alexa, Google Assistant, Siri) do this, because they don’t seem to differentiate between, “Are you capable of doing x” and “Do x.” I spent a little bit of time messing with my own Google Assistant to try to find a situation in which I could force it to make that differentiation; the best I could manage was that it would count to 10 if I asked it, “Can you count to 10?” but if I asked it, “Can you count to 1000” it essentially said that it could do so but it would take a very long time, so it wouldn’t and I should pick a smaller number instead.

Anyway, as a general rule having to hard code things like this is not the best way to do things, and it would be much more useful and scalable if AI had both a better fundamental understanding of ISAs and a recognition of the fact that humans are highly likely to use them. Indeed, the study showed that “indirect speech acts were used by the majority of participants and constituted the majority of task-relevant utterances.” While humans who interacted with the robot for a little bit quickly figured out that ISAs were not effective, and it’s likely that some instruction up front would have avoided the problems completely, it’s not necessarily reasonable to assume that a naive user would have a pleasant or efficient experience, as exemplified by that sample conversation.

The researchers also speculate, however, that even if people know that avoiding ISAs is the most effective way of communicating with a robot, the perceived impoliteness of it may still make it difficult in some scenarios. And anyway, don’t we want robots to learn how to interact with us, rather than the other way around?

Ideally, future research on natural language understanding would develop mechanisms whereby robots can automatically learn to understand ISAs in general, or to understand specific newly encountered ISA forms, which would allow robots to adapt to their human users instead of requiring the opposite.

“‘Thank You for Sharing that Interesting Fact!’: Effects of Capability and Context on Indirect Speech Act Use in Task-Based Human-Robot Dialog,” by Tom Williams, Daria Thames, Julia Novakoff, and Matthias Scheutz from the Colorado School of Mines and Tufts University, was presented earlier this month at HRI 2018 in Chicago.

Thanks Jan for the glass of water photo, via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)!

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.