Changes in language happen organically and deliberately. John Koenig, filmmaker and creator of the multimedia Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, is working on the latter, filling in linguistic holes with a compendium of subtle emotions for a new age.

His dictionary provides formulations for feelings we all have but aren’t named. Some are new, products of postmodern life, while others are especially acute now that we’ve lost the emotional language for home.

Vocabulary isn’t created in a vacuum. “Each word actually means something etymologically, having been built from one of a dozen languages or renovated jargon,” Koenig explains. For example, liberosis is a longing for liberty, an ache to let things go. A recent addition, wytai, is an acronym for “When You Think About It,” and means the sudden realization of how absurd some aspect of modern life is.

The dictionary is a work in progress made up of website, videos, graphics, and will be published as a book next year by Simon and Schuster. Sonder–the realization of the richness of other people’s lives–is a much beloved 2012 entry with more than 40,000 notes from fans on the compendium’s website.

Inventing words isn’t a new sport, however, so maybe Koenig was feeling anemoia, or nostalgia for a time he never knew. Charles Dickens made up curses so as not to offend Victorian readers, like gormed, considered horrible although rooted in the mild Irish word, gom, meaning to look. George Orwell invented newspeak to describe opposite talk used to obfuscate rather than illuminate. It swiftly entered common parlance, conveying the peculiar creepiness of this speech. Before the novel 1984 was published in 1949, no English word gave the same sinister sense, and today the “speak” suffix, as in corpspeak, still indicates dangerously fake language, thanks to Orwell.

The precise expression, le bon mot, is prized worldwide. Swedes neatly articulate living arrangements, differentiating between rooming with a cool parent, kobo, bunking with a lover, sambo, and living apart from your romantic partner, sarbo. The Japanese have a word for the literary affliction of buying unread books, tsundoku. German’s concise complexity has prompted English to borrow many words, including schadenfreude, or taking pleasure in the misfortune of another. It got so popular that the New York Times advised giving schadenfreude a rest.

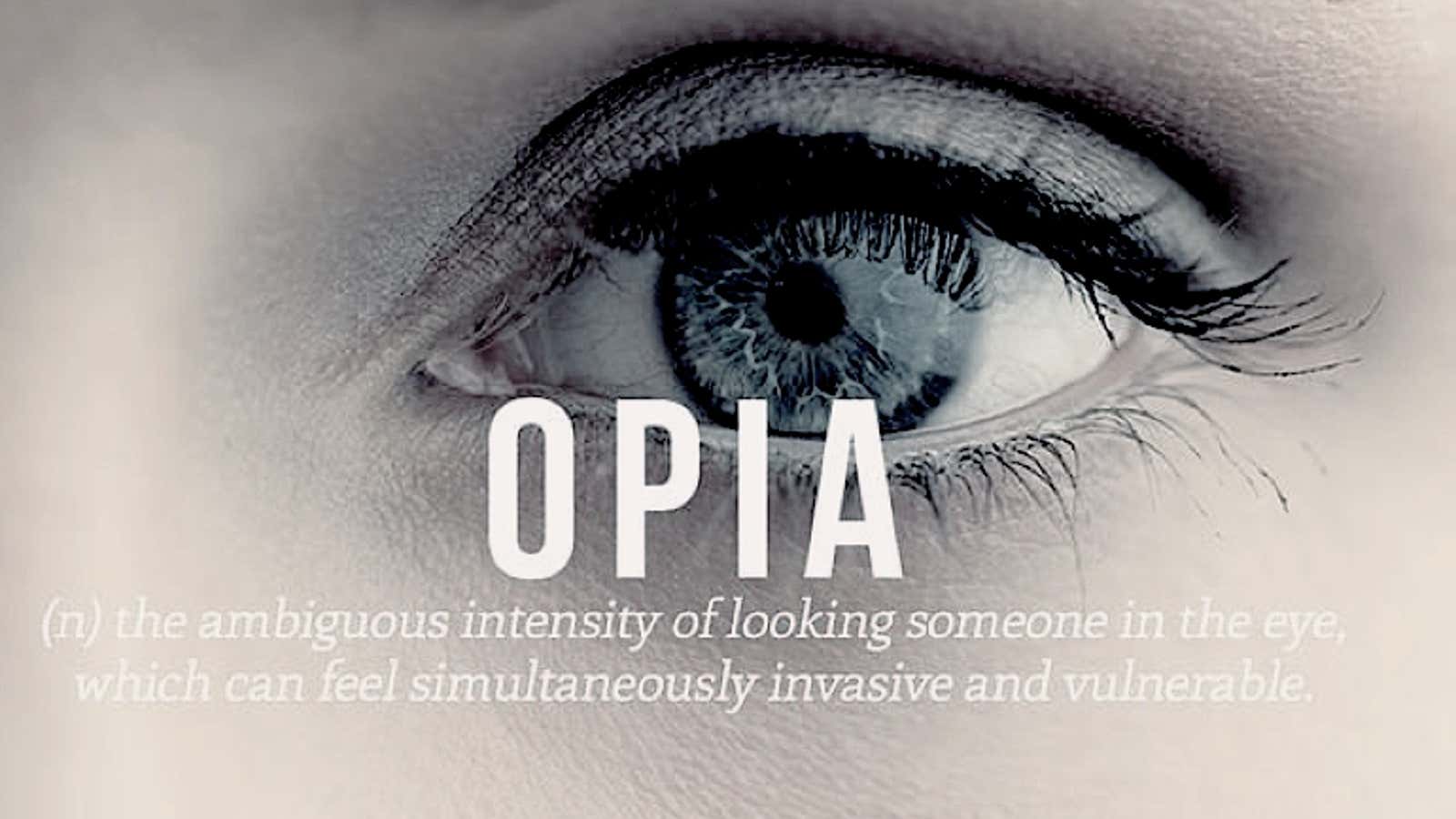

The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows joins this endeavor, adding shades of gray to the emotional space with words like zenosyne, or the fear that time is speeding up. Koenig is also open to suggestions for entries in the compendium. Only subtle expressions need apply.