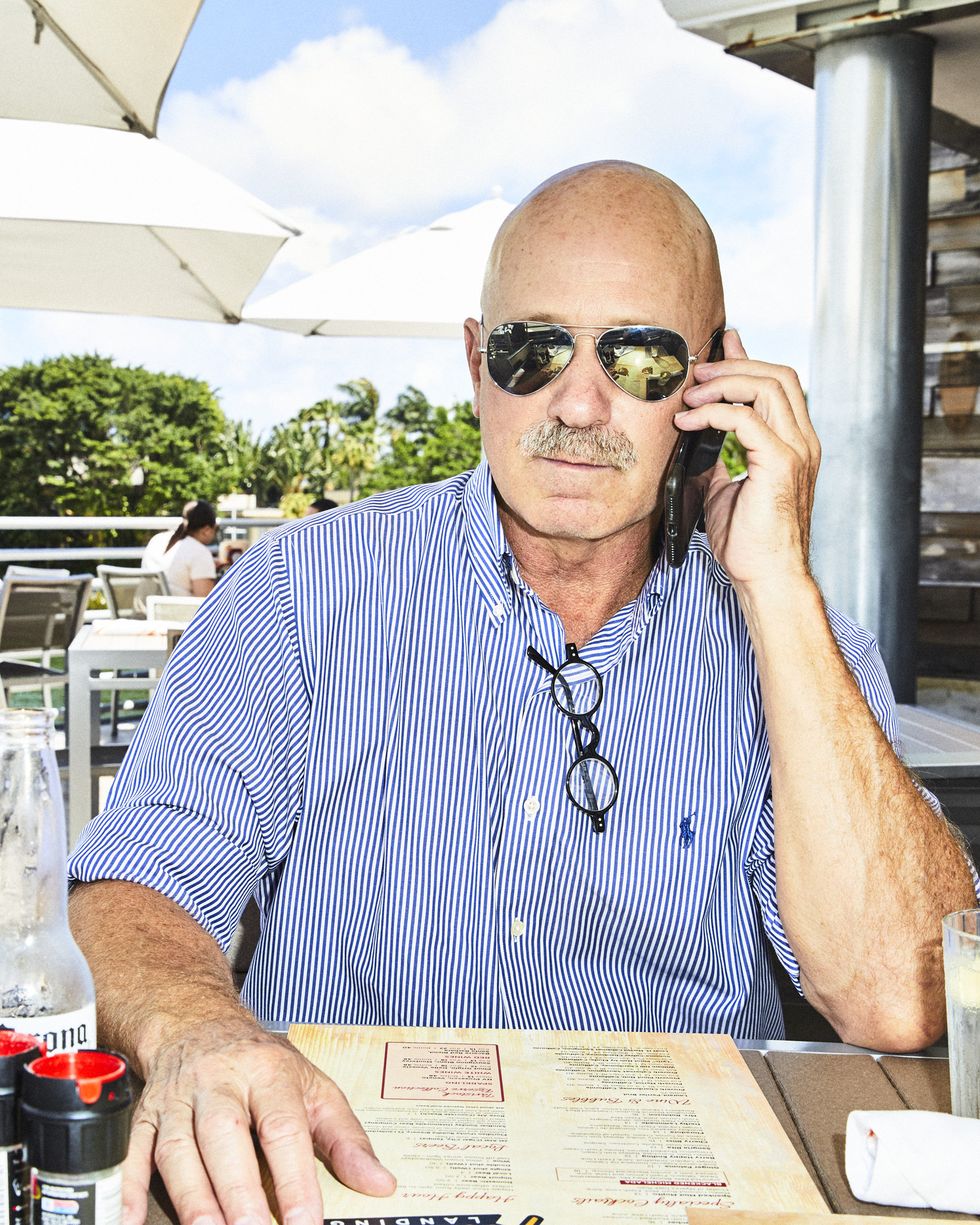

Joe Ford is sitting at the Pelican Landing, an outdoor restaurant in a fancy marina on the Intracoastal Waterway. Across the way is a 180-foot yacht, the name abbracci painted across the stern.

Joe’s cell phone rings. Wah-wah-waaahhh.

The theme music from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Joe’s ringtone.

“Hold on,” he says. “It’s the FBI.”

It’s midday, and Joe has just finished his first Corona. He’s self-employed. The Pelican Landing is off the main channel in Fort Lauderdale, part of the Pier Sixty-Six Hotel & Marina, a twenty-two-acre, four-star resort where deckhands refuel yachts before they sail out to sea. When you’re sitting at the bar, the boats look like shimmering skyscrapers. Crew members scrub down decks; owners sip cocktails and shout into smartphones.

It’s a place Joe goes.

He hangs up his call. “The FBI says this is the most fun case they’ve ever worked—and I’m going to help them solve it,” he says.

He looks around, nods at the Abbracci, once owned by a Texas businessman who recently sold off seventy-eight rare automobiles for a total of $53 million. “If you can afford that, then you can afford a million-dollar car,” he says, by way of explaining that lunching at this high-end grill is an essential part of his work. His order of ceviche and plantains arrives, and Joe orders another Corona.

Joe is a detective for hire who specializes in recovering stolen cars. But not your car. Joe doesn’t look for cars stolen from parking garages or shopping malls—everyday transportation whose value lies in the number of miles they carry us. Joe Ford specializes in recovering cars whose value lies in not being driven much at all: rare, collectible, fetishized cars that are worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, sometimes millions or tens of millions of dollars, prized not for their ability to get from here to there but rather for their beauty, the artistry of their design, the care with which they were built, and perhaps most of all, their provenance.

“I’m in a niche of a niche of a niche,” he says.

Joe, sixty-two, is more Magnum P.I. than Sam Spade—tall, trim, tan, usually wearing a fitted polo or a Hawaiian shirt. Drinks sweet tea by the gallon and speaks like the New Orleans native he is. (“I grew up in east New Orleans, near the Ninth Wah-ard.”) Likes to swim and dive for lobsters and drive boats. He recently cruised on a sixty-five-footer down to Utila, “this coral-reef island off the coast of Honduras,” he says. “It was incredible—diving with whale sharks and drinking with outlaws. One guy didn’t come back.”

People end up doing all kinds of jobs in this life. You sometimes wonder if, given a few left turns and different choices, the guy playing center field at Yankee Stadium could have ended up a taxi driver instead. Or vice versa. But Joe . . . Joe Ford is what happens when a particular set of skills, personality traits, and turns of phrase lead a person into the only thing he should be doing. It’s rare. And when you see him at work—when you see him move easily among both the shady creatures of criminality and the millionaires on those yachts—you wonder whether you, like him, have found your place in the world.

The FBI agent was calling about a new lead in Joe’s current case. It’s a big one, the kind that could set Joe up for a long time. Maybe help him get his own boat, his own rare sports car. Help his daughter be more comfortable as she copes with the disease that’s taking away her eyesight. Help him disappear into the sunset.

He’s been working this case for six years. “Everyone loves cars, but this is different,” Joe says. “At this level, it’s about bragging rights for the rarest and the best. That’s what makes the Teardrop so coveted.”

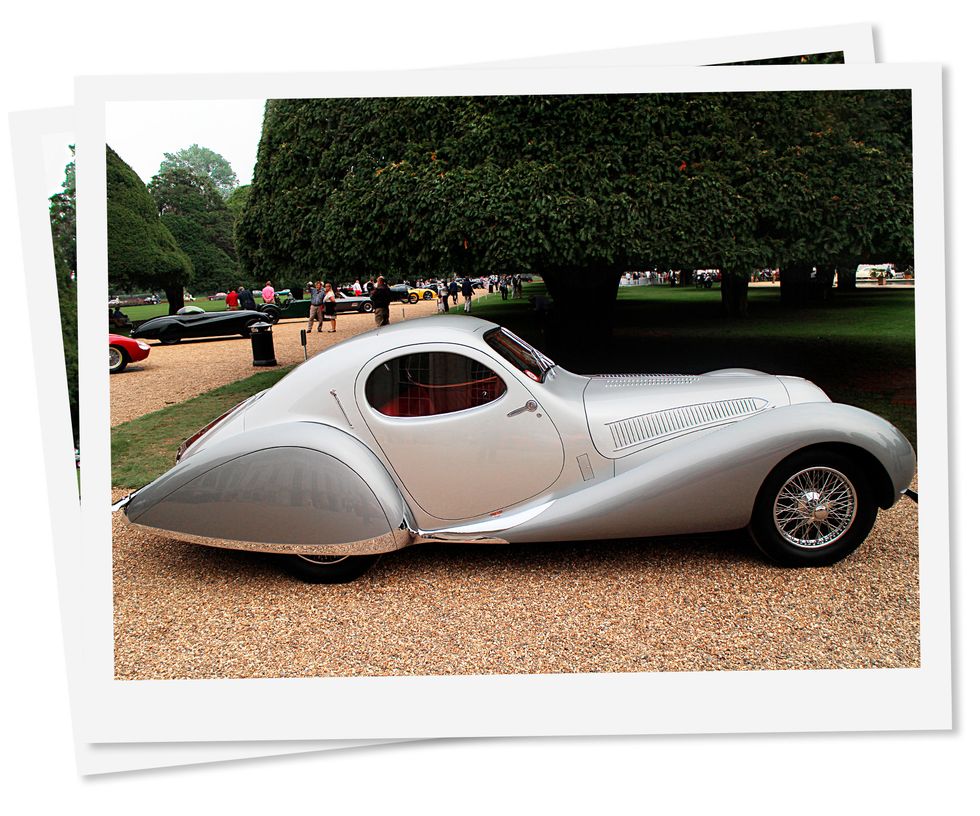

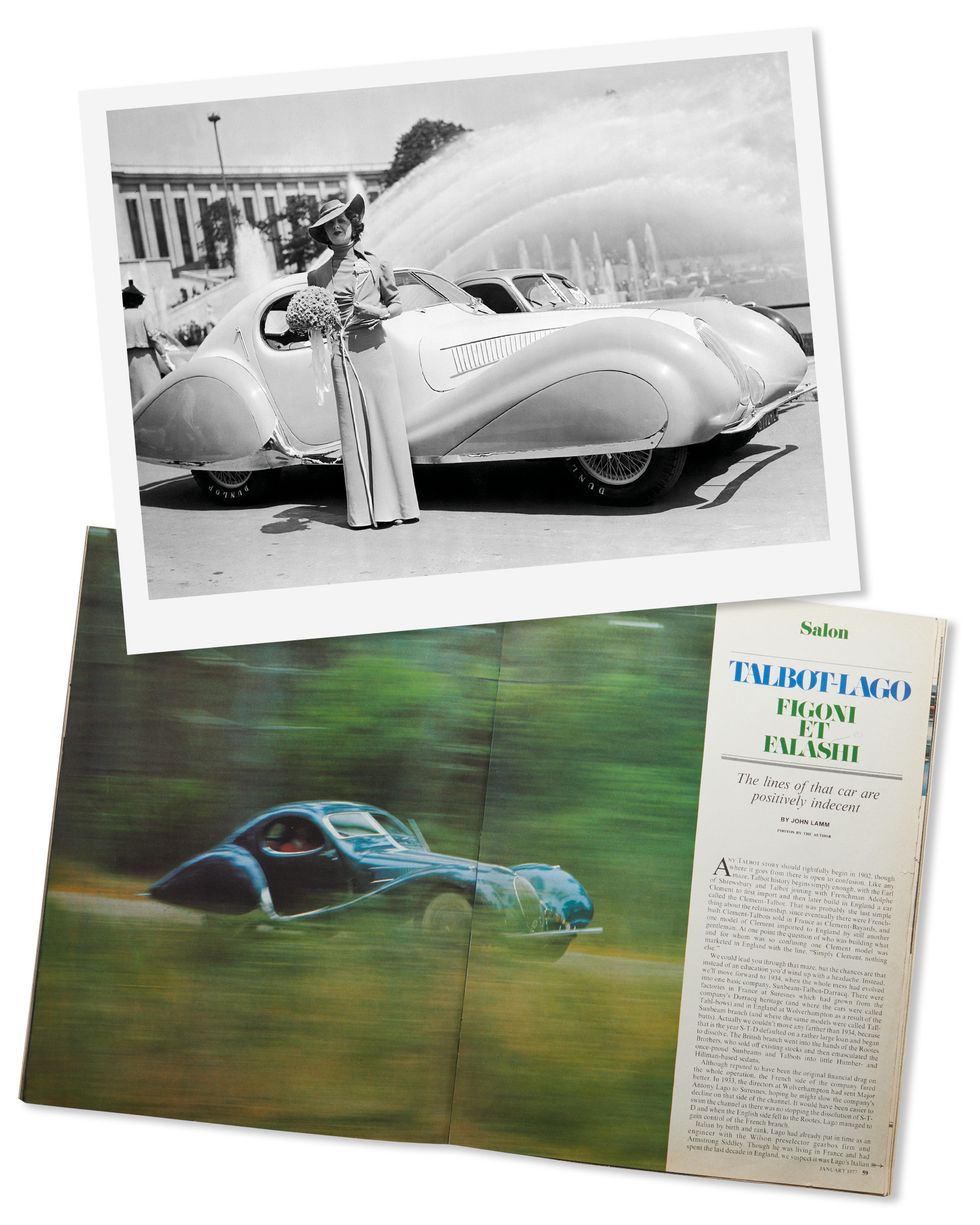

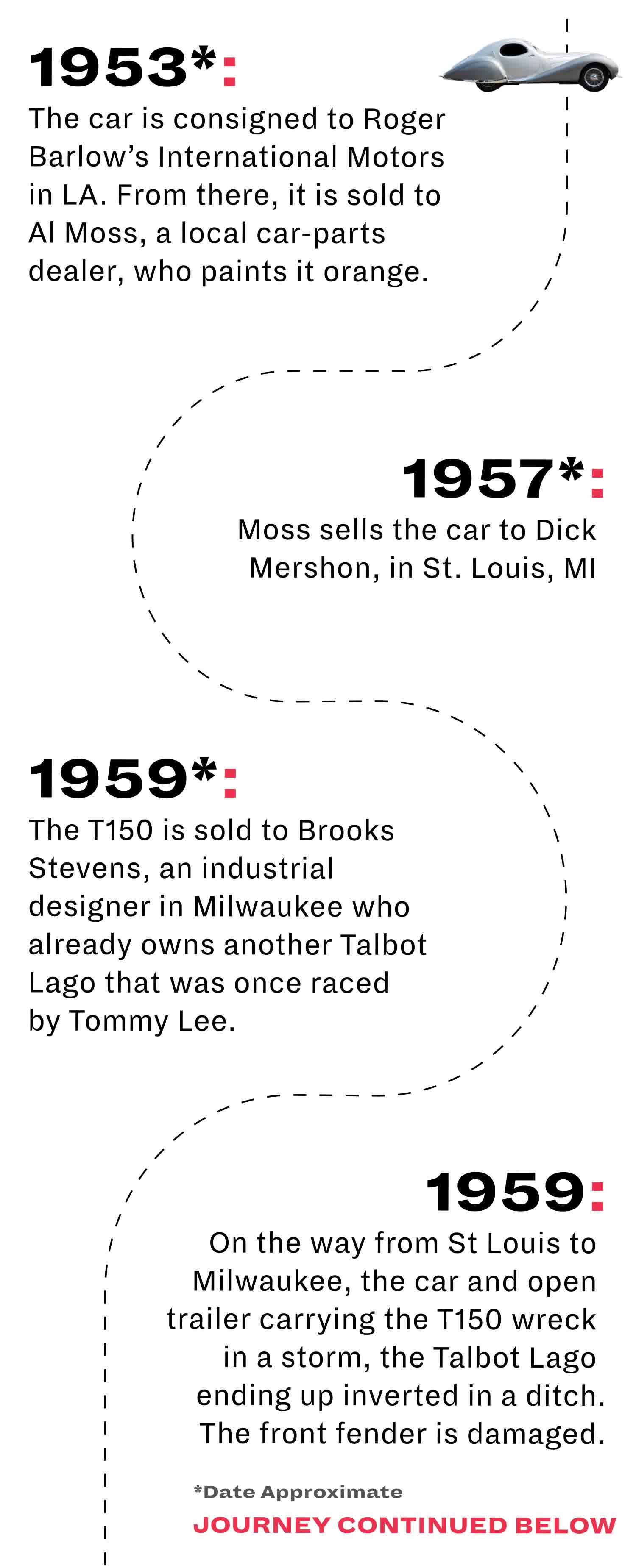

The Teardrop. Otherwise known as the 1938 Talbot-Lago T150C SS teardrop coupe, chassis number 90108, current value $7.6 million. Built by two men, names of Figoni and Falaschi—Italian immigrants to France who ran the world’s top custom-car shop in Paris from the thirties through the fifties—the T150 is a prime example of a model that the Robb Report once called “the most beautiful car in the world.” One of only two models built with a race-car engine, it’s an art deco masterpiece, a long, sleek body powered by ground-shaking horsepower. The C stands for competition—it gets 140 bhp out of a 3,996cc six-cylinder engine—but the Teardrop was built as rolling art, a metallic blue car with a red leather interior and red wire wheels. It’s shaped like a teardrop, pure aerodynamics.

When it debuted, its wealthy owners commissioned custom wardrobes to match its colors and lines—society-page fixtures using it to make grand entrances at balls.

The T150, chassis number 90108, however, now holds another distinction: It was stolen in one of the boldest automobile heists in history. In fact, one of the most brazen and spectacular heists of any kind at all.

And Joe Ford, a P.I. from Fort Lauderdale nursing a Corona who has to get home to walk his girlfriend’s teacup poodle after she goes to work, is working his ass off to get it back.

“Some cars speak to me,” he says, finishing his beer and heading to get his parking validated. “This one screams.”

The rare-car market is like a pyramid.

The base layer is mostly American cars of the fifties—Bel Airs and Packards in garages across the U. S. that can sell for up to $125,000. Next come the muscle cars and rarer European cars—Mustangs, Mercedes, Jaguars. They can go for up to $350,000. At the top are the European racers and one-of-a-kind creations whose blend of history and craftsmanship can put their value in the millions: a Ferrari raced at Le Mans, perhaps, or a ’68 Mustang driven by Steve McQueen. A 1927 Bugatti Royale, one of six ever made, a twenty-one-foot-long, seven-thousand-pound commercial failure upon its debut, would be worth an estimated $100 million should one ever become available. In 2017, classic cars topped the Coutts Passion Index, a list of the British bank’s top passion investments, increasing in value by more than 300 percent in the past decade to bypass assets like wine, jewelry, and artwork.

Like jewelry and artwork, valuable cars are stolen. Thieves have pulled off elaborate heists of million-dollar vehicles, sometimes smuggling them to international locales, retrofitting them with fake paperwork, and then reselling them on the global market.

That’s when people call Joe.

Joe is staring at what appears to be a cherry red 1951 Ferrari 340 America Berlinetta. “Look at this engine,” he says. “You’d never know this car wasn’t the real thing. Just a beauty.”

He’s at the Creative Workshop, an automotive restoration and replication shop in Fort Lauderdale. The FBI has just recovered the Talbot-Lago’s missing engine from a mechanic in the French Alps, and Joe will need to have it inspected—but first he needs an expert mechanic. The Creative Workshop is a garage you could live in: high ceilings, hardwood floors with a rustic patina, exposed beams—plus tool chests, hydraulic lifts, blaring rock music, and a fleet of candy-colored, multimillion-dollar cars arrayed like Hot Wheels.

Tattooed experts carefully plug horsehair into seats, bend wood into dashboards, and replicate ancient paint colors with homemade mixtures in order to ensure each vehicle has the most accurate features possible—a process that can cost millions.

Joe shakes his head, admiring the craftsmanship.

On one recent case, he tracked down a mechanic who ran a seemingly respectable shop overseas, only to discover he was conducting a side business in black-market replicas. “Just like there’s art forgeries, there’s classic-car forgeries,” Joe says. “There’s an old expression in the business: In the thirties, the Mercedes-Benz factory built twenty-five special Roadsters, but only thirty of them survived.”

In the wrong hands, the 1951 Ferrari—built from scratch for a Mexican businessman who wanted an exact copy of the original—could be sold on the black market with forged papers, passed off as the real thing. But Jason Wenig, who owns the Creative Workshop, vets his customers’ vehicles, ensuring clean chains of title. His cars—whether replicas or restoration jobs—don’t get into the wrong hands.

Joe smiles. He feels he can trust Wenig—a feeling in short supply these days. The Talbot-Lago case has brought in the FBI, Interpol, and even an enemy he never would have suspected: his former friend, who turned on him. Joe has ringed his home with security cameras and taken up his old pastime of shooting targets with a Beretta.

“Every story needs a villain,” Joe says. “In this one, it’s him.”

Here, as briefly as possible, is what happened to Joe’s Talbot-Lago:

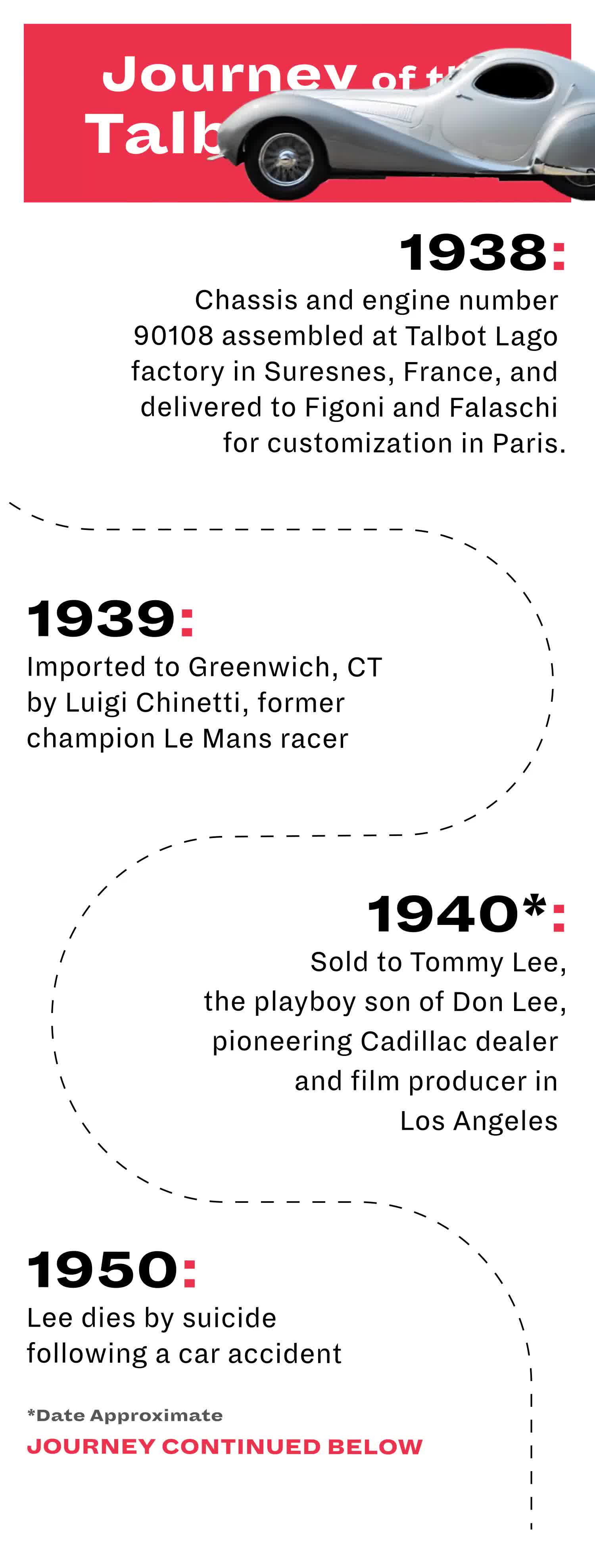

It was imported into the U. S. in 1939 by Luigi Chinetti, an Italian race-car driver who won Le Mans three times. That year, Chinetti sold the Teardrop to Tommy Lee, the son of a radio and television broadcaster who also owned Cadillac dealerships throughout California. Lee lived the playboy life, dating starlets, racing cars in the Mojave Desert, and amassing a collection that included four Talbot-Lagos. In 1950, following a road accident that left him in chronic pain, Lee leaped to his death from a twelve-story building, leaving behind a world-class collection of cars—including the Teardrop.

For decades, the car was bought and sold until, in 1967, it wound up in a cluttered garage in east Milwaukee owned by one Roy Leiske, a self-made millionaire and the founder of Monarch Plastic Products, a company he ran in a warehouse near his home.

In 1962, Leiske’s wife died of cancer. In 1996, his son, a pilot, died in an airplane crash. Leiske abandoned anything that resembled the life he had been living—everything except the Talbot-Lago. He shut down Monarch and became obsessed with the Teardrop. He spent his days tinkering with the car amid towering piles of machine parts.

Collectors traveled to see it, and some tried to buy it, with everyone from Jay Leno to people who might be described as “international businessmen” making the trip. (Leno didn’t make an offer.)

Leiske never sold.

One day, in 2001, it disappeared. Early in the morning, men in white overalls parked an unmarked white box truck in front of Leiske’s former factory. They cut the phone lines at his home. For years, the Teardrop had remained in pieces at the back of the former factory, its parts in various spots, its paperwork scattered among office drawers.

Somehow, the thieves knew exactly where to look for all of it. They used an overhead crane in the building to move the Teardrop’s parts into the box truck, according to neighbor eyewitnesses.

At 10:00 a.m., Leiske arrived to drink his coffee and begin working on the car, as he did every morning, only to find that all the parts and paperwork—even receipts dating back to the sixties—were gone. No sign of a forced entry. Nothing else was taken.

Four years later, Leiske died. He left the car—which he technically still owned—to Richard Mueller, his second cousin and only living heir, who figured he’d never see the vehicle again.

Joe lives in a development a few miles west of the $15 million mansions lining the sea, on the workaday side of the Intracoastal Waterway. Lago Del Mar, the developers called it—a ring of townhouses with miniature lakes, palm trees crawling with iguanas, and a pool for the residents, all amid an endless tract of cheek-by-jowl houses, single-story shops, eight-lane roads, and municipal golf courses. There’s a synagogue across the street from Lago Del Mar and a shopping center a few blocks away.

Joe pulls his weathered SUV into the complex and parks at his place, next to a tarp-covered sports car—a 1976 MGB two-door convertible he hasn’t driven in months. “The battery’s dead,” he says. Ancient seabed fossils, megalodon shark teeth, and plaster molds of Renaissance statues decorate the tidy two-story condo. He collects these, always has. When he was a landlord in New Orleans, he had to dig around his own foundation during a restoration of his 1832 townhouse. As he worked through layers of silt, he discovered tiny combs and trinkets, and they fascinated him.

The centerpiece of his home: a four-foot-tall antique replica of an eighteenth-century Spanish galleon, the kind of ship whose wrecks once left sunken gold throughout the Gulf of Mexico, one of several on display. “I’ve always been a treasure hunter,” he says, adjusting a tiny hand-carved cannon on the ship. “When I was a kid, I read about guys who moved here to Florida to hunt treasure, finding mother lodes of gold. It’s just cool.”

He lives with his girlfriend, Shari, a knockout who waitresses at a high-end restaurant at a nearby resort; Shari’s dog, Charlie; and Joe’s teenage son, one of his four children from a previous marriage—the older three have grown and gone.

Of all his kids, only his daughter, Julia, has left Florida—she works as an analyst at a software company in Washington, D. C. As a child she was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a rare disease that slowly deteriorates the retina and leads to vision loss and in some cases total blindness. Joe is proud of what she has nonetheless accomplished—landing a top job, spending years living abroad, even going bungee jumping—but the disease haunts his thoughts. “She’s down to 10 percent vision, so she’s trying to do as much as she can now,” he says, fixing a glass of sweet tea. “She’s running a marathon in Hawaii this weekend.” He pauses, staring at the glass. “I try not to think about it. But I can’t imagine the world shrinking like that for her. It’s the hardest conversation to have.”

Up in his office on the second floor, he squints at a blurry photo of an engine block on his computer. Surrounding him are marksmanship trophies, grease-stained auto manuals, and a wraparound monitor that engulfs his wooden desk.

“I like a big screen because I can move things around,” Joe says, toggling between black-and-white engine photos, police reports, and a news story about the San José, a seventeenth-century Spanish ship that’s been discovered off the Colombian coast with $17 billion in gold. “Those guys are the real cowboys,” Joe says. He clicks back to the engine photos. “But I’m still catching fish.”

There is no online database of rare cars, no central resource. Instead—in addition to the requisite globe-trotting, interviewing of sources, and general sleuthing—Joe reads. He owns every issue of Road & Track through the seventies, rare-car books in French and Italian, manuals from Ferrari, and even some personal diaries of racers, in which he pores over hand-scribbled victories in order to verify a car’s provenance.

Joe heads downstairs to find his son—slim, tall, wearing a T-shirt—padding into the kitchen. He’s got a date tonight.

“Where you taking her?” Joe asks.

“Houston’s.”

“Not bad.” Joe reaches into his billfold and slips the kid a hundred.

A question: Is the son of the world’s greatest car detective into cars?

“Kinda,” the teenager says, shrugging, heading back upstairs.

Joe laughs, finishing off his tea. “He’s into washing my car,” he says, then pauses. “He’s a good kid. Smart. Wants to study finance at NYU. It’s more expensive than Harvard. But I said, Yeah, if you get in, I’ll pay. I’ve just first gotta find this car.”

Joe grew up in the sixties and seventies, one of five kids of an Air Force–pilot father and a mother who kept house, a military household he says was loving yet stern. As a young teen, he raced motorcycles with a group of neighborhood kids, camping along the Gulf Coast and hunting wild game for food.

“We would ride motorcycles and then tear them apart, seeing how they worked,” says Bruce Graham, a childhood friend. “Joe was like the professor of our group, very smart—but he liked to have fun.” Joe went to an ROTC high school along Lake Pontchartrain, where he practiced sharpshooting. Sprawled on his belly with a .22, he learned to control his breathing, slow his heart, and blast quarter-sized bull’s-eyes from one hundred feet away without a scope. Later, between architecture classes at Tulane, Joe started another hobby: cave diving. He’d drive to the Florida Panhandle and dive into spring-fed bayous, navigating underground chasms that had never been mapped. “You go through a chimney at the bottom of a bayou, and then it opens up to a cavern and then another cavern,” he says. “It was just fantastic. The only way you knew which way was up was to see your bubbles. You had to be cool as a cucumber and trust your equipment. Otherwise you’d be fucked.”

In 1980, Joe graduated from Tulane; married his college sweetheart, Tessie; and started having kids. The architecture thing didn’t work out, so he thought: lawyer, good money. To get himself through law school, he got in on something he’d learned about a few years earlier: buying and selling European sports cars.

While taking law school classes at night, Joe found another niche by day: gray-market cars. These were cars built in Europe in the middle of the twentieth century—vehicles like the MG, Triumph, and Jaguar, sleek racers with giant engines that dominated anything coming out of Detroit. American GIs noticed them during World War II and brought them home.

By the mid-eighties, Americans were importing upward of sixty thousand gray-market European cars per year. “I said, This is better than sliced bread,” Joe says. “Here I am at a desk working my butt off, and these guys are doing well importing cars. I gotta get into a different business.” Joe started importing Mercedes. Then Black Monday happened—the October 19, 1987, stock-market crash—deflating the dollar and drying up the import business. So, shit. But Joe found a new opportunity and helped pioneer a new approach: gray-market exports. He began by focusing on Jaguars. “With the dollar weak, Europeans started coming over here to purchase all these classic sports cars that had been leaving their countries for years, buying them at half price. So I started exporting—riding a whole new wave,” he says.

Over the next five years, Joe built a car-export business in New Orleans from scratch. He drove around the United States in his battered Chevy Blazer, placing ads in newspapers and magazines, buying up used Austin-Healeys, MGs, and Jaguars. He took side roads, barreling down dusty lanes looking for rare cars in garages and barns, knocking on farmers’ doors to persuade them to sell. When not on the hunt, he was on the phone, making connections with European importers and flying cross-country for handshakes. He was building a global web of contacts.

And he started to make a little money. He stored cars in his garage in the French Quarter before taking them to commercial docks in New Orleans, Miami, Newark, Jacksonville, Charleston, and Mobile, shipping them across the world. “He put over five hundred thousand miles on that diesel Blazer,” Graham says. “Nobody else was doing this. He showed me his garage once and I said, Jesus, Joey, you’ve got over $900,000 of cars here!”

Joe’s family still hoped he’d be a lawyer. But by this point, he’d decided he was making so much money in gray-market Jags—and having so much fun—that this would be his livelihood.

“I’d driven a different E-type Jaguar to law school every day,” he says. “My mom said, Get a job! But I said, No, I’m finally making it.”

Back in New Orleans in the late eighties, Joe met a businessman named Christopher Gardner, who introduced him to the gray market. They worked together for a while and both ended up moving to Fort Lauderdale. They became good friends—really good friends. But in 1992, their relationship soured. Joe had bought Gardner’s Florida home, which, according to Joe, had a cracked seawall he wasn’t told about, costing him tens of thousands of dollars. They didn’t speak for years, and Gardner eventually moved to Switzerland to set up a rare-car business.

Then, in 2005, Gardner reappeared. Called Joe out of nowhere and said that he had shipped an Aston Martin to a shop in the southeast U. S. and paid $25,000 for a repair and that the car had disappeared. He wanted Joe to find it. Joe said he would.

He visited the shop, posing as a potential customer, and soon discovered a key piece of information: Gardner had a personal connection to a relative of the garage owner, but they’d had a falling out. Figuring the garage owner had decided to hold Gardner’s car out of spite, Joe worked with local police to investigate him. “I prepped the file for the police, and they muscled the guy,” Joe recalls. “Then we got the names of some friends who had been storing it for him . . . and they coughed up the car.”

Joe Ford had a new career.

For the next few years, he worked with Gardner and other clients, building a reputation as a guy who could find missing vehicles.

In Miami, he went undercover in high-end repair shops, vetting mechanics’ trustworthiness for collectors. In Texas, he looked for a rare Ferrari engine that had been placed in a speedboat and had torn through the hull, sinking in the Houston Ship Channel.

He even brokered the trade of a vintage Ferrari Daytona for a brand-new Testarossa from California, ensuring the cars were what the parties claimed.

But no job would compare with the one involving the most expensive vehicle of Joe’s career, a stolen car that would ultimately ensnare international authorities and nearly leave him bankrupt: a 1954 Ferrari 375 Plus “spider.” “Gardner and I did three or four deals, and then the Ferrari popped up on our radar screen,” Joe recalls. “And that’s when he went to the dark side.”

The only thing more incredible than the spider’s eight-figure price tag is its history. The first of only a few ever made, it was built with a twelve-cylinder, 4.9-liter engine, able to reach speeds of up to 185 miles per hour, an astounding feat at the time. In 1955, Karl Kleve, a car collector and former nuclear scientist on the Manhattan Project, bought the Ferrari. For decades it sat on his Cincinnati property amid piles of scrap metal.

Then, on a dark night in January 1989, thieves broke in and used a hand-operated winch to roll the spider onto a U-Haul. The car was later sold via a broker to dealers in Belgium, where it was restored and even exhibited until Kleve, working with the FBI and Interpol, finally tracked it down.

Lawyers got involved. The car sat in Europe. Eventually, Gardner heard about it and asked Joe to take a look.

After Kleve’s death, Joe worked with his heirs to gain part ownership and traveled the U. S., interviewing past owners and authorities and tracking the car’s provenance. He put together a case and helped work out an agreement to auction the car and settle all claims. But things began to unravel. Joe says Gardner had initially agreed to bankroll the legal work but hadn’t paid a cent. Then he’d broken all contact with him.

This was odd. Gardner had brought Joe into the deal. Was it possible that he was squeezing him out?

It’s a long story, but . . . yes. The Ferrari was eventually sold at Bonhams auction house. The price: an astounding $18.3 million. The buyer: Les Wexner, the billionaire founder of L Brands, which owns Victoria’s Secret. The result: another quagmire of litigation.

After two years, Wexner got his car and Bonhams took a hit in the press. In the course of the un-quagmiring,

Joe finally got a piece of the winnings, but the legal wrangling had decimated his earnings. Even worse, he had lost someone he thought was a trusted friend: Gardner. According to Joe, Gardner had secretly maneuvered behind the scenes to get the auction to proceed over Joe’s objections, asserting that Joe no longer had any legitimate claim on the vehicle. Ultimately, after the Bonhams sale, the proceeds were distributed to everyone involved to make them all go away—leaving Joe with a fraction of what he otherwise would have received.

“He and I would have earned millions,” Joe says. “But what I later learned is that he had cut me and the Kleve heirs out totally, claiming he owned 100 percent of the car, an out-and-out lie.” Gardner had been accused of unsavory dealings in the past. Joe didn’t know it at the time, but in a 1989 court filing, assistant U. S. attorneys in Louisiana charged Gardner with “smuggling ten used foreign-made automobiles into the United States by means of false documents.” (Gardner pleaded guilty to two counts of knowingly concealing facts, and the additional counts were dismissed.) Classic-car collectors in Cooper City, Florida; Seattle; and Brescia, Italy, had claimed in court filings that Gardner had sold them fraudulent 1930s Horsch Special Roadsters and Alfa Romeos and owed them hundreds of thousands of dollars. “Gardner could provide no paperwork,” claims Richard Scott, one alleged victim, who paid $300,000 for what he thought was a Roadster. “At this point, it is believed [the car shell] is some sort of custom body, made after the war, and as such has a value of less than 20 percent of the price that I paid for it.”

Gardner did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story.

Joe didn’t emerge from the Ferrari case unscathed, either. He had originally partnered with Kristine Lawson, one of Kleve’s daughters. In the past year, she sued him, claiming she should have received more money from the sale. Joe settled the suit. Then, just this past February, Lawson’s two sisters, Karyl Kleve and Katrina English—who had been represented by Lawson and Joe in the lawsuit—filed another suit against a different set of former attorneys, hiring one of Gardner’s former lawyers and claiming that Joe had not been fit to be their counsel.

Calling Joe a “south Florida hustler and con man,” they said they had only received $150,000 apiece from the sale of the Ferrari, while Joe took $2.4 million. (The suit, which was not against Joe but nevertheless took a shot at him, alleged that $1.1 million of that amount went to pay for Joe’s legal fees during years of litigation against Gardner. Joe says the whole issue was between the sisters and not him.) Although Joe says he got “seven figures” from the sale of the car, he claims legal fees have eaten up a lot of it and that his remaining funds are now in jeopardy thanks to yet another suit related to the Ferrari case.

“It’s taking a few twists and turns,” Joe says of the case. “It’s a tactical thing. They settled with everybody but me in order to paint me as the rich guy. . . . I’ve filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and it’s going to federal court.”

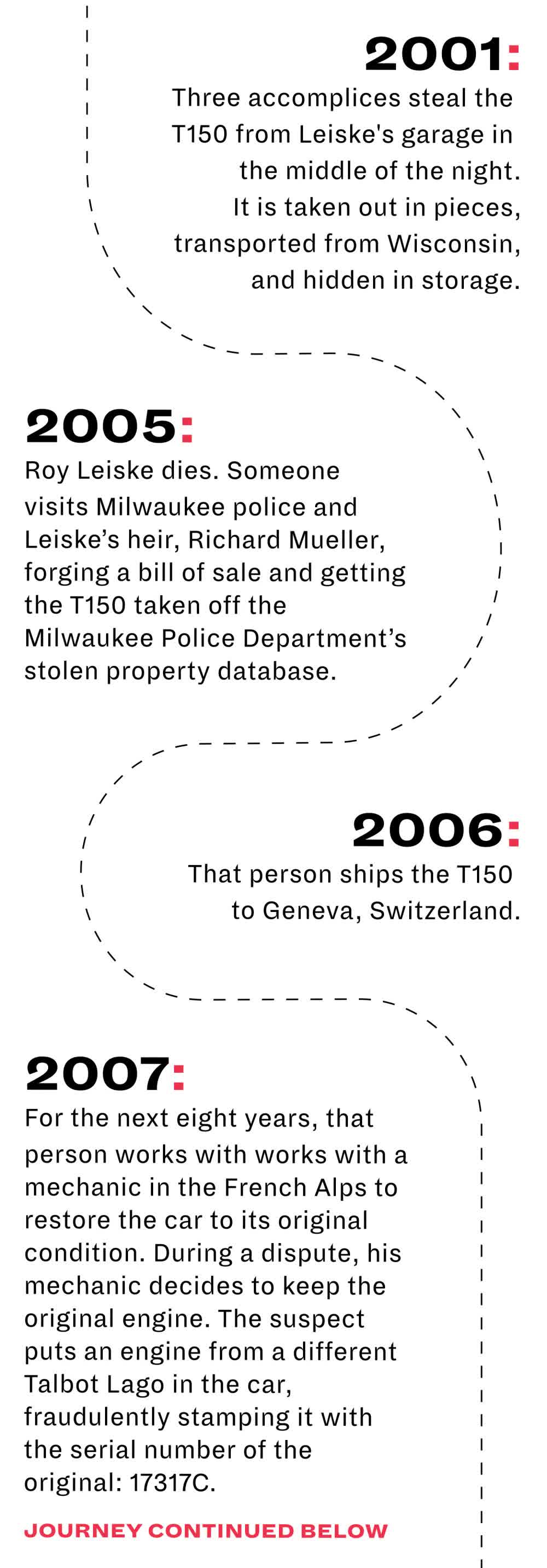

But there was one silver lining. During the Ferrari case, a French mechanic had told Joe about a car Gardner had stolen: the rare Talbot-Lago. So, during the deposition, Joe decided to see if it was true. His attorney asked Gardner about the car to see what he would say—and caught him in a lie. “Gardner claimed he had bought the Talbot-Lago from an estate,” Joe says. “But I checked, and the estate did not sell the car. So that’s when I knew Gardner was a fucking liar and was fabricating documents to launder a stolen car. The car had been stolen.”

Back when Joe had first called Mueller—the second cousin of Roy Leiske, who inherited the title to the stolen Teardrop—Mueller told him he had gotten a call from a man in 2005 who had asked about buying some old parts from Leiske’s garage. “Then he asked about the stolen car,” Mueller says. The guy’s name? Chris Gardner.

Joe asked Mueller if he wanted to work with him, and Mueller jumped at the idea. He offered Mueller his standard deal: Joe would search for the car, paying his own expenses, in exchange for a majority ownership. If it was recovered, he would sell the vehicle and share the proceeds with Mueller.

Joe started his research. He ordered rare histories of the Talbot-Lago and French manuals that chronicled its mechanical details, and he contacted car clubs in Europe, paying locals to read through race records. He traveled to Milwaukee to review fifteen-year-old police documents, working backward to piece together the story of the Teardrop. “I’m trying to find when it was made, who bought it next, was it dismantled for steel during the war, whatever,” Joe says. “Provenance.”

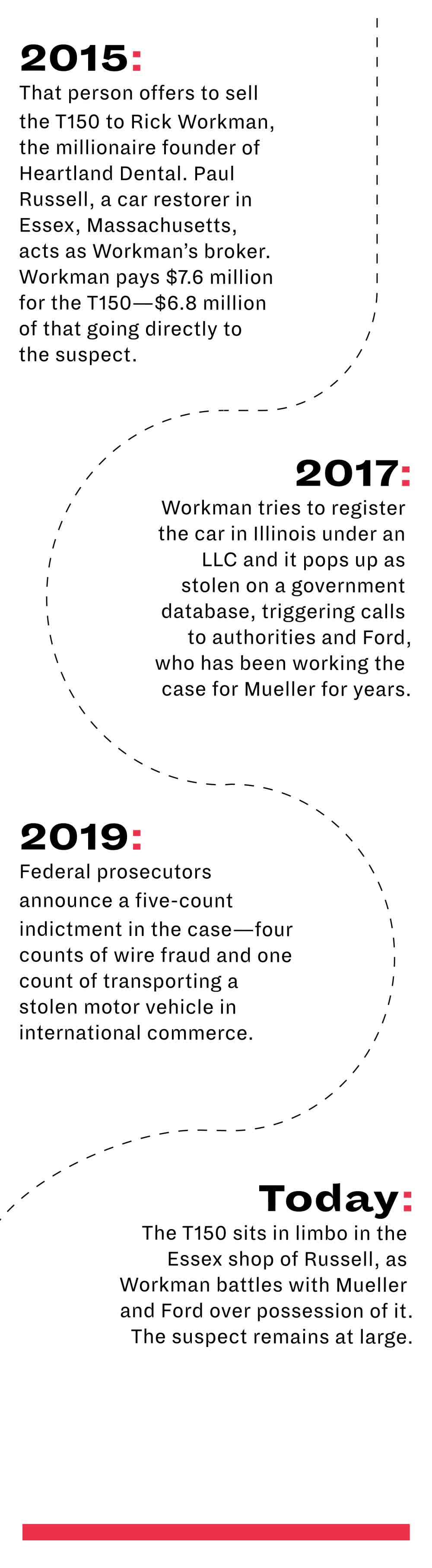

For two years, Joe went to work crafting a history of the Teardrop. But his leads took him nowhere. Then in 2016, he got another call. The Teardrop had resurfaced in Illinois, now apparently the property of a Rick Workman, the millionaire founder of Heartland Dental, a nationwide back-office administration company for dentists that Bloomberg once called the corporate “Walgreens for the dentistry business.”

Workman had bought the Teardrop—from Gardner. Somehow the stolen Teardrop had ended up in the hands of Joe’s friend turned enemy, who had sold it for more than $7 million to the novice collector. “Workman is the new whale,” one car collector says. “He’s recently wealthy, a self-made millionaire, and also a recent entry to the classic-car market—which means he’s now on everyone’s Rolodex.”

Workman tried to register the Teardrop in Illinois under a corporation, and it popped up as stolen on a government database. Motor-vehicle authorities contacted the Milwaukee police, who called Mueller—its rightful owner—and the FBI. Mueller, who was then working with Joe to find the car, demanded the return of the Teardrop.

Workman refused. So in 2017, Joe and Mueller sued Workman for its return. They lost a decision in circuit court and then won on appeal, and the case is scheduled to go before the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

“I respect Workman,” Joe says. “I even met him at last year’s Cavallino Ferrari event at Palm Beach. I said, We find ourselves on opposite sides of the fence, but I hope we can work this out. You got snookered.”

On a warm morning in May, Joe is in the gleaming, eighty-two-thousand-square-foot regional headquarters of the FBI near Milwaukee, on the shore of Lake Michigan. The room is airy and filled with sunlight. Joe stands alongside a couple FBI agents wearing polos, jeans, hiking boots, and badges around their necks. Mueller is there, along with his lawyer.

In front of them, Joe’s long-sought goal: the Talbot-Lago engine. FBI agents seized it from the mechanic in France—the same mechanic who told Joe about the car in the first place—who had flipped to help them. Joe carefully removes parts of the engine from a crate, inspecting and documenting them piece by piece, helping the FBI verify their provenance. He finds a hinge to the rear trunk lid. Some chrome trim. A metal rod with some of the car’s original paint, a crucial link for tying all of this to the original vehicle.

Nothing, however, compares to the motor itself—a shiny two-carburetor racing engine that has traveled the world for nearly a century to wind up in Milwaukee. Following the engine’s theft from Leiske in 2001, its original serial number was ground off. But over the past few weeks, since seizing it in France, the FBI was able to use chemicals to trace the fatigue left from the original stamping, raising a ghostly image of the serial numbers and identifying it as the original motor.

“This is some top-level science by guys who know their shit,” Joe says. “It confirms it’s the original motor, and once it’s done as evidence, they’re going to release it to me and Richard. A $2 million engine.”

Today, Joe is wrapping up a Midwest field trip, one that involves both his detective and legal skills, visiting the FBI as well as Workman’s lawyers in Chicago. A few days ago, in a conference room on the seventy-first floor of the Willis Tower in Chicago, Joe—wearing a fishing shirt and jeans—met with two of Workman’s top lawyers in the headquarters of Schiff Hardin, a national firm. Joe was there to give them one last shot at redemption.

“I said, Listen, guys, the reason I’m here is that you’ve wasted $5 million of your client’s money,” Joe says. “I was willing to settle in the beginning for $3 million, dropping our lawsuit. But since then, another Talbot-Lago has sold for $9 million, and I’m about to meet with the FBI about the [Teardrop’s] engine, currently worth $2 million. Give me the stolen property now and then go after the real villain for your money. He’s going to jail—and I can help you with that.”

Joe has never worked in a law firm. But he keeps up his legal license in Louisiana, studies the specifics of the law wherever he’s working a case, and then does his own legal work, representing himself in courts from Ohio to London to win cars. “Joey’s not corporate material, but he’s better than any corporate lawyer I’ve ever met,” Graham says. “I once ripped the bottom of my $200,000 catamaran, and the insurance company was not going to pay for it. Joey did all the legwork. They ended up paying me half a million dollars for that boat. I would have lost if Joey wouldn’t have stepped in. There’s a lot of good lawyers out there, but a lot of them charge you for nothing. And he makes an ass out of them.”

On this trip, Joe couldn’t persuade the lawyers to give up the case—even though he claims the state of Wisconsin will never allow Workman to keep stolen property. “I gave them an opportunity to be the good guys, give me the car, and then I’d help them go after the villain,” he says. “I said, If you take this to court, you’re going to lose. You’re misapplying a tort remedy statute, trying to trick the court into applying it to criminal theft—it’s a Hail Mary pass.” Joe sighs. “The other lawyer said, Well, Joe, that’s the chance we’re willing to take.”

Joe may have struck out in Chicago, but he hit gold with the FBI outside Milwaukee. Although he still has to win the Talbot-Lago from Workman in court, he and Mueller are guaranteed to receive the engine—all thanks to the trickery of Gardner.

In the course of his investigation, Joe learned that the French mechanic had originally tried to sell the motor to a representative of Workman, who didn’t bite. So the mechanic next tried to sell it to Joe—whom he knew through his years with Gardner—saying he could ship it from France through a car-restoration shop in Milwaukee. Joe informed the FBI, who then had him set up a meeting with the car-shop owner—a rep for the mechanic.

“This was a high-end shop,” Joe says. “I told the guy the engine was stolen and I’d only pay him a finder’s fee. But he didn’t do anything, and the deal fell through. They must have sniffed it out.”

Joe figured that was the end of it. In the following weeks, however, the FBI and Milwaukee police traveled to the mechanic’s shop and, along with French police, interrogated him. Initially, the mechanic mouthed off to them. But after his arrest, he became cooperative, giving them the motor as well as his computers and files, which contained information tying him to what Joe believes is a $60 million network of international car thieves—all run by his former friend.

“The FBI won’t tell me shit,” Joe says, speaking hours after leaving the FBI headquarters. “I know it’s going to be a long indictment, and they’re poised to arrest Gardner, but they just won’t tell me when or where.”

He sighs. “I can tell you this: His goose is cooked.”

On May 30, a federal grand jury in the Eastern District of Wisconsin released a five-count indictment against Christopher Gardner, charging him with wire fraud and causing a stolen car to be transported in foreign commerce.

“A guy from the Milwaukee newspaper just called me about it,” Joe says, pausing to look at his phone. “Holy shit, it’s already on Fox News.” Gardner is believed to be living in Mont-sur-Rolle, Switzerland. The investigation that led to his indictment involved the FBI, the Milwaukee police, Homeland Security Investigations, and the French National Police. If convicted on all counts, Gardner, sixty-three, could face thirty years in prison.

Just the week before, Gardner had posted images on Instagram depicting him smiling in a red racing suit next to an antique car at the Vintage Revival event in Montlhéry, France. “Swiss helmet,” his caption stated with a Swiss-flag helmet emoji. Then his Instagram account was almost entirely scrubbed.

“We’re looking and appealing to the public to help us identify and locate him,” says a rep for the FBI.

The investigators analyzed the whole complicated history, and slowly the complete story of the Talbot-Lago’s journey tumbled forth. According to the indictment, it was Gardner and two accomplices who, in 2001, broke into Roy Leiske’s garage in east Milwaukee, working quickly to extract the Talbot-Lago. After its theft, Gardner transported it to California, where it was kept in storage.

Then, in October 2005, just months after Leiske died, Gardner returned to Wisconsin to visit Mueller, who, figuring the Teardrop was gone for good, had no idea Gardner was the one who had stolen it. Leiske had kept a second Talbot-Lago as a parts car, which Gardner offered to buy. Mueller sold it to him.

Which meant that Gardner had Mueller’s signature.

Gardner used the signature and bill of sale to forge documents of ownership for the real Teardrop. He contacted the authorities in Milwaukee to affirm that he was in lawful possession of the car. According to a 2005 police report, Gardner provided a copy of the bill of sale and (falsely) told authorities he had bought additional parts for the vehicle from a classic-car specialist in Stockton, California, and then promised to contact the police if he ever learned “the identities of suspects in the initial burglary.”

Incredibly, the Milwaukee police didn’t question the story and didn’t call Mueller. A report was written stating that the Teardrop had been “recovered,” and it was removed from the government’s stolen-car database.

Gardner then shipped the Teardrop from Oakland to Geneva to the mechanic’s shop in the French Alps, but in the course of the restoration job, Gardner stiffed the mechanic. Out of spite, he kept the original engine. Unfazed, Gardner simply placed a different Talbot-Lago motor from the same period into the car—eventually selling it to Workman for $7.6 million in 2015. By this point, Joe and Mueller had placed the vehicle back on the government’s stolen-car database, triggering authorities when Workman tried to register it the next year—leading to the current international crime scene and legal shit storm.

Through a rep, Workman—whose corporate bio says he “grew up on a farm, has a car collection, was a DJ in college”—initially declined to comment for this story. After the indictment, however, his lawyer issued the following statement: “[Dr. Workman] purchased the vehicle in good faith for fair value. He has fully cooperated with the ongoing investigation into Mr. Gardner. Since the investigation in Mr. Gardner is pending and civil litigation over the vehicle is continuing, Dr. Workman cannot further comment until those proceedings are concluded.”

“Friday afternoon—time for beer and oysters.”

Joe is sitting at a plastic table at the Southport Raw Bar, a dockside shack tucked behind a strip-mall dive shop near the Fort Lauderdale airport. A locals joint, the bar is adorned with Christmas lights, kitschy signs, and a narrow view of an industrial boat slip looking east to the Atlantic. “I’ve been coming here for years,” Joe says, sucking down an oyster. “Someday I’ll have my own boat here.” Joe is a man who found his place in the world. He is doing what he was meant to do, and he’s thinking about the future. He’s got a whole file of new leads. People heard about the Ferrari and Talbot-Lago cases, and he’s getting calls from around the world. He’s looking into a missing car in the former Soviet bloc, “where they’ll kill you for a million-dollar vehicle. Not sure I want to touch that one yet.” He’s searching for a wealthy collector who angrily bulldozed a barn full of rare cars after a fire destroyed a few—Joe is convinced he can pull out the chassis from the dirt and get them restored. “Back then, the cars weren’t worth what they are today,” he says. “The former landowner is dead, but I’m using Google Maps to search the area. It might be under a highway; I’m not sure.”

First up: He’s thinking about the case of a Ferrari owner in California whose vintage $5 million racer has gone missing in Asia. “When he said Asia, I said, Oh fuck, good luck with that,” Joe says, finishing his drink. “But then I said, Tell me more.”

This article appears in the September 2019 issue of Esquire

Subscribe