At the Guardian we make changes to the website codebase several times a day, from small style tweaks to new features and obligatory refactoring. Multiple teams work on different parts of the website. While coordination is necessary, each team is independent, deploying their changes without going through a heavy process or a central QA entity.

This flexibility helps each team or individual contributor develop their idea quickly, iterate it, and improve it. But it raises the question of reliability: how can we minimise coding errors while developing at a rapid pace?

Our development process is built of simple but powerful tools and processes, which together help us be confident of our code changes

Code review

Every single code change is submitted as a pull request to the repository. There are no formal rules dictating how code reviews should be conducted, but it is understood that you must obtain the approval of at least one other developer to be able to merge one’s changes – usually a developer who is already familiar with the piece of code concerned.

Code reviews have two very important purposes: sharing knowledge and improving code:

Sharing knowledge

A reviewer familiar with the code can provide additional context and make sure the changes have no unexpected effects that would have been overlooked by the submitter.

Encouraging several developers to read and understand code ensures that no subpart of the codebase is known only to a single person. Developers move between teams, priorities, and companies. Code reviews help to share ownership of the codebase.

Improving code

The obvious role of a code review is to detect and fix bugs before they make it into the master branch.

Code reviews are also used to discuss and improve design decisions. A solution that works is not necessarily the best in terms of maintainability or performance, for example.

Continuous Integration

The Guardian website codebase is linked to a build and continuous integration server (in our case, Teamcity).

Every change, on every branch, triggers a build job that ensures:

- All tests pass (more than 1800 at time of writing).

- The applications can be built successfully.

Any failure would lead to the pull request being marked as failing; no executable would be produced, preventing accidental deployments of a broken build.

A CI job currently takes about eight minutes every time a change is pushed to the github repository.

Staging environment

We maintain a staging environment that is very similar to the production one (including https support and services topology). We call it “CODE”.

Testing on code is not mandatory, but we encourage developers to check their changes on this staging environment.

We mentioned earlier that every single change results in the CI server producing a new build executable. It is then very easy for developers to manually deploy their build to the staging environment. Given the size of our teams we can get away with coordinating the staging deploy queue using a simple Slack channel.

We trust developers to use their best judgment to decide if a given change must be checked on staging. We found this system to be very flexible while making it easy to extensively test riskier changes before releasing them.

Automatic and autoscaling deployment

At the Guardian we practise continuous deployment: every merge to master triggers a build on our CI server. If tests are green and the build is successful, it is automatically deployed.

It takes usually less than 15 minutes for a change to be deployed to production once the code is merged into the repository’s master branch.

The Guardian website runs on Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Riff-Raff (our in-house deployment tool) allows us to use the AWS Autoscaling feature to achieve no downtime deploys.

Riff-Raff uploads the new build to S3 and then doubles the size of all the services’ autoscaling groups. New instances fetch the new build from S3 at startup, and run it. Once all instances have successfully started, Riff-Raff terminates the instances running the old build and brings the autoscaling groups back down to their original size.

Result: no downtime and a smooth transition from one build to another.

A critical piece of the puzzle is the service healthcheck endpoint.

For those who are not familiar with AWS Elastic Load Balancer healthchecks, here is what the AWS console says: “Your load balancer will automatically perform health checks on your EC2 instances and only route traffic to instances that pass the health check. If an instance fails the health check, it is automatically removed from the load balancer.”

New instances that don’t respond with a “200 OK” to the ELB healthchecks won’t get any traffic and are quickly removed from the load balancer pool. Riff-Raff will mark the deployment as failed and clean up all the instances running the new build, bringing back the service cluster to its original state before the deployment attempt.

For this process to work, every service has a ‘/_healthcheck’ endpoint. While it could be a ‘dumb’ endpoint returning a static 200 response, we opted for healthchecks that exercise real routes and real code paths. This ensures that a successful healthcheck response means the service can serve real content.

We also use a tool call PRout that tells developers when their pull requests are live. Developers don’t need to wait and actively check for the deployment to finish; PRout will notify on Slack and add a pull request comment when the changes have been seen in production.

PRout has also an ‘overdue’ feature which notifies developers when their changes are not live after 30 minutes, so they can investigate why the deployment has not been successful.

As you can see, deploying the Guardian website requires very little human intervention and is composed of a set of fail-safe operations that would prevent most “problematic changes” to ever make it into production. Along the path, the developers are assisted by powerful tools, making the process automatic while reporting progress and failures.

Making sure we are confident with our new code doesn’t end with successful deploys. We have a set of mechanisms and systems like alerts and monitoring to ensure our production environment operates smoothly.

Using the CDN to our advantage

Most of the content accessed on the guardian website is highly cacheable. We use this property to our advantage by setting up our very customizable CDN to serve stale content if our servers return errors. This prevents our readers seeing these errors, even though new stories won’t be accessible during this period.

This “serve stale if error” mechanism doesn’t prevent issues happening in production but it allows us to minimise the impact of such errors on Guardian readers while we’re fixing the underlying problem.

A very quick fix would be to manually revert to the latest known working version. This takes only a few clicks with the Riff-Raff web interface and 3-4 minutes for the full deployment to complete.

Monitoring

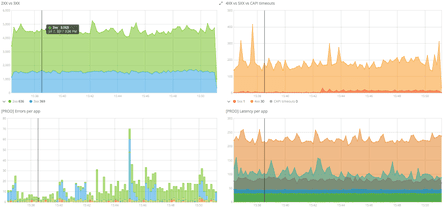

Being able to quickly know the state of a system and diagnose issues when they arise is very important. To achieve this we have set up extensive logging of our server-side code, that is stored in an Elasticsearch cluster and queried with Kibana. This Elk setup give us near real time logging capabilities and powerful aggregation features.

Alerting

AWS Cloudwatch alerts have been set to watch significant metrics (ex: load balancer errors count and latency) and notify the team via email/Slack when a threshold is reached. It allows us to react immediately when something bad happens without having to continuously keep an eye on our monitoring dashboards.

Conclusion

All the steps and mechanisms described in this post are simple and relatively easy to set up. Individually they do not ensure the complete reliability of our code, but collectively they help us remain confident that every change we release into production is reliable, and that our development process is as fast and frictionless as possible.

What’s next?

Finding the perfect balance between safety and flexibility is not easy: this process is the result of months of trial and error in order to adapt it to the needs of the guardian digital team. We are always looking to improve it to reduce blockers and mistakes. Let us know if you notice anything we would have missed.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion